A new study from the International Renewable Energy Agency laying it out in detail. Large wind power farms got cheaper between 2010 and 2014.

Large-scale solar power got a lot cheaper. And at least some renewable plants are even becoming competitive with new fossil-fuel plants:

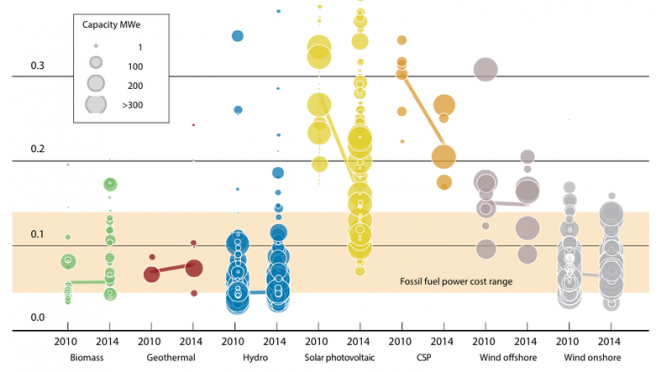

The chart shows the “levelized cost of electricity” for different utility-scale renewable projects built in 2010 and 2014. This is an oft-used metric for comparing different energy technologies. It’s a ratio of how much money a power plant costs over its lifetime to how much electricity it will generate. So it factors in construction costs, fuel costs, financing, and how often a plant is used. Notably, it doesn’t factor in any subsidies that governments may provide.

Two big things stand out:

1) Wind and solar power are getting cheaper. As the chart above shows, the cost of large utility-scale photovoltaic plants and concentrated solar power plants have dropped sharply. Projects built in 2014 had a lower lifetime cost per kilowatt-hour than projects built in 2010. Both offshore and onshore wind farms also got cheaper, though the decline isn’t as dramatic.

By contrast, biomass, geothermal, and hydropower are all pretty mature technologies that haven’t seen big drops in cost lately.

For all technologies, there’s a wide range, since the cost of individual projects can vary dramatically from place to place. All else equal, wind turbines in windier areas will operate more often and have lower lifetime costs per kilowatt-hour than those in less-windy areas. More efficient technologies or cheap financing can also bring costs down. (That helps explain why solar power is three times costlier in sunny Central America than in North America.)

2) In some regions, renewables are getting competitive with new fossil-fuel plants. This point needs caveats, but it’s striking. The chart below has a beige box showing the range of estimates for building new coal or natural gas plants. The average cost of onshore wind is now well within that range. And in North America, utility-scale solar photovoltaic plants are creeping into range:

(IRENA)

Now, these numbers leave a few things out. They don’t include the cost of backing up intermittent sources like wind and solar. After all, if you build a solar farm, you may need back-up power or energy storage for when the sun’s not shining. That’s an extra cost and a real disadvantage for renewables, particularly as wind and solar become a bigger part of the grid.

At the same time, these cost numbers also don’t factor in the damage caused by fossil-fuel pollution — including global warming. That’s a big disadvantage of fossil fuels. The chart below shows what happens if you factor both those things in. Wind is still competitive, as are the cheapest solar farms:

(IRENA)

Okay, now the caveats. These charts don’t mean that renewables are now just as cheap as fossil fuels or that it will be cost-free to replace all our coal and gas plants with wind farms and solar panels.

This doesn’t mean that solar and wind are as cheap as fossil fuels everywhere

For one, theses charts are only comparing new solar/wind plants with new fossil-fuel plants. But countries like China have already built plenty of coal plants with lifespans of 40 years or more. All else equal, it’s usually cheaper to keep an existing coal plant running than it is to tear it down and build something new. (Though stricter air-pollution regulations could change this calculus.)

Second, different solar and wind projects have a wide range of costs. As the charts show, many solar plants are still vastly more expensive than fossil fuels. What’s more, power companies still have lots to consider when deciding whether to build, say, a new wind farm. What subsidies are available? What’s the existing resource mix? How often would the turbines operate? Will this wind farm require additional back-up generation? Are fuel prices likely to fluctuate? And so on.

That calculus will change from place to place. As the US Energy Information Administration warns, it can be misleading to read too much into average levelized cost of energy estimates.

That all said, the fact that renewables keep getting cheaper and are moving within range is notable. Increasingly, there will be places where it may make financial sense to rely on wind and solar instead of coal or gas (especially if there are subsidies, though sometimes even if they aren’t). At the margins, lower costs will help boost the growth of renewables and reduce the costs of policies to promote clean energy.

The report also argues that wind and solar costs are likely to keep falling in the future. Interestingly, the big gains are expected to come not from a reduction in equipment costs, but rather from a decline in “balance of systems” costs and cheaper financing. We’ve seen that in the United States, where companies like SolarCity are finding ways to make it easier for homeowners to finance rooftop solar panels. It’s worth watching how similar innovations spread overseas.