The temperature increases by 30 ºC for every kilometre further underground. This thermal gradient, generated by the flow of heat from the inside of Earth and the breakdown of radioactive elements in the crust, produces geothermal power. About 500 power stations around the world already use it to generate electricity, although there are yet to be any in Spain.

However, the subsoil of the Iberian Peninsula has the capacity to produce up to 700 gigawatts if this resource was exploited with enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) at a depth of between 3 and 10 kilometres, where the temperatures exceed 150 ºC. This is confirmed in a study that engineers from the University of Valladolid (UVa) have published in the journal Renewable Energy.

“The operation of an enhanced geothermal system uses the injection of a fluid (water or carbon dioxide) to extract thermal energy from the rock located a few thousand metres below the surface, and whose permeability has been improved or stimulated previously with fracturing processes,” explains César Chamorro, one of the authors. “Afterwards, the heated fluid is taken upwards to the geothermal station, where it produces electricity, generally via a binary cycle (exchanging heat between the water and an organic liquid), and it is re-injected into the site in a closed cycle.”

Although there are experimental EGS stations in countries such as the United States, Australia and Japan, there is only one connected to the grid: Soultz-sous-Forêts in France. The rest of the current geothermal stations are in the few areas of the world where there are thermal anomalies and the presence of hot water at a shallow depth.

“Nevertheless, EGS resources are distributed widely and uniformly, meaning they have enormous potential and could supply significant power in the medium or long-term, 24 hours a day constantly,” points out Chamorro, who makes this comparison: “The 700 GW of electricity indicated in the study represent approximately 5 times the current electrical power installed in Spain, if we add together fossil fuels, nuclear and renewable power.”

Technical and renewable potential

“Even if we limit the calculations to a depth of 7 km, the potential reaches 190 GW; and for between 3 and 5 km it would be 30 GW,” adds Chamorro. All of this data refers to the so-called ‘technical potential’;, which entails a cooling (using water) of 10 ºC in rocks that are at least 150 ºC to extract a fraction of energy during the 30-year operating period.

There is another renewable or sustainable potential, which only considers the electrical energy that could be obtained if the thermal flow was harnessed at the rate it arrives at the crust from Earth’;s core. This value is significantly less, and in the case of Spain is estimated at 3.2 GW. “It seems low, but it is the equivalent of 3 nuclear power stations,” states the engineer, who clarifies that the installable power limit would be somewhere between the technical and the renewable potential.

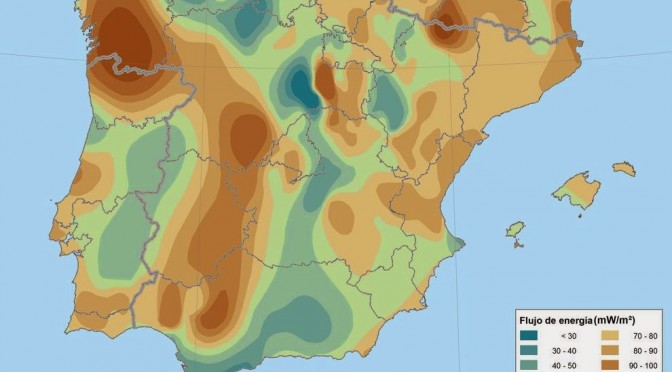

According to the study, the regions which reach the highest temperatures at shallower depths, and therefore, have greater geothermal potential and are prone to more detailed studies for their development are Galicia, western Castilla y León, the Sistema Central mountain range, Andalusia and Catalonia. The reason is that there is greater friction in their subsoil between the base plates and presence of granite materials. The results are on a regional scale and therefore, the installation of a geothermal station in a specific place would require more detailed studies.

To estimate the temperature at various depths (from 3,500 m to 9,500 m depth) the researchers have used the heat flow and temperatures at 1,000 m and 2,000 m provided in the Atlas of Geothermal Resources in Europe, as well as thermal data of the land surface available from NASA.

Applying the same information to the whole of Europe, the researchers have published another study in the journal ‘Energy’;, where they compare the potentials of each country. Turkey, Iceland and France show the greatest potential. Altogether the technical potential of the continent exceeds 6,500 GW of electricity.

With regards to the implementation of EGS technology, the authors recognise that there are still significant problems that must be researched, such as the appropriate perforation technique, the best way of fracturing the rock or how to operate advanced thermodynamic cycles.

“But when these are resolved we can move on from the technical feasibility reached now to economical feasibility which allows for their commercial operation,” Chamorro points out. According to a report from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), in 2050, after suitable investment in R&D, 100 GW of electricity could be installed with this technology in the United States.

“In the case of Spain, EGS systems could significantly contribute to the national energy mix, reducing energy dependency on other countries and cutting greenhouse gases,” the engineer concludes.