Growing economies like China and India, which are set to contribute more than half of the global increase in carbon emissions in the next 25 years, will play a critical role in any effort to address climate change.

Shortly after Modi took office in May, one of his party officials made a sweeping promise: India would develop enough solar power to run at least one light bulb every home by 2019. The goal is part of a larger push to boost renewables in India, where energy demand is projected to double over the next 20 years.

But even with a drastic boost of renewable energy, India faces a formidable challenge in weaning itself from coal, which accounts for 59 percent of its electric capacity. That dependence on fossil fuels is why India ranks fourth behind China, the United States, and the European Union in global greenhouse gas emissions.

Aggressive Goals for Renewables

Modi’s government has put forth a slew of ambitious renewable energy goals. The country’s minister of power and energy, Piyush Goyal, told a gathering of wind turbine makers in August that he intended to add 10,000 megawatts of capacity to the sector every year—that’s about half of the country’s current total installed capacity.

Goyal added that the government would go “far beyond” the previous regime’s 2009 goal of installing 20,000 megawatts of solar energy capacity by 2022. Even the previous regime’s target could potentially power 10 to 15 million households, or the entire Delhi metropolitan area, according to Chandra Bhushan, head of the industry and environment program at Center for Science and Environment, a New Delhi-based public interest research group.

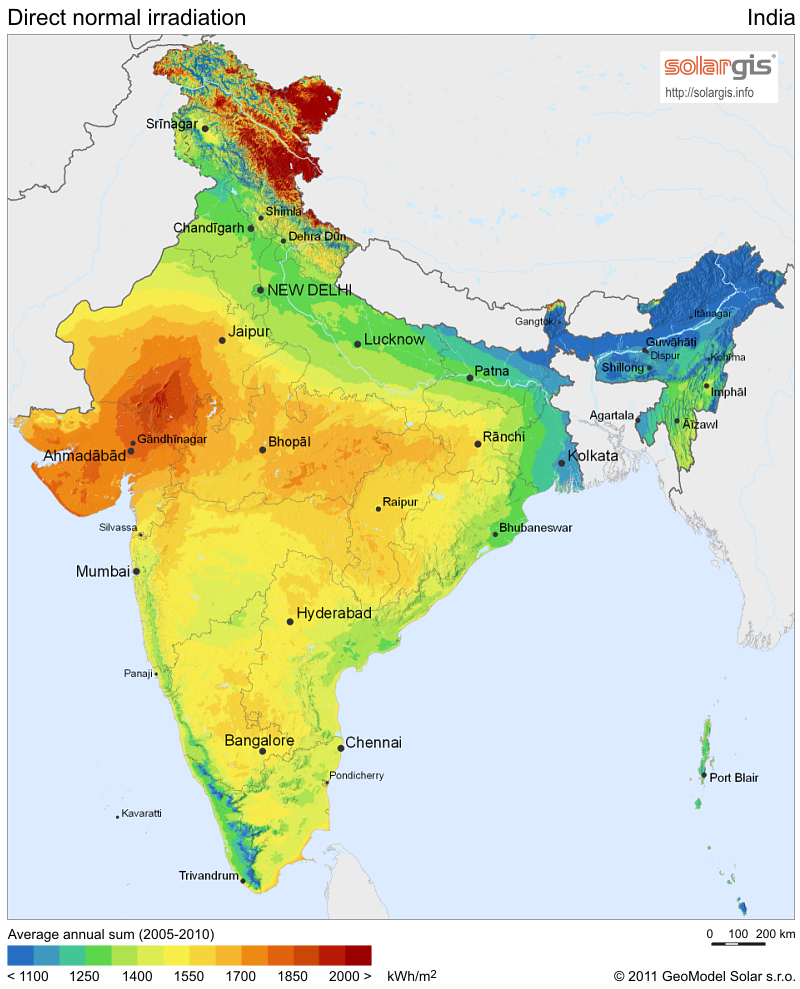

Targets and talk aside, much remains to be done in both the wind and solar sector. Large-scale state-sponsored programs have helped India boost its solar capacity by a factor of a hundred between 2011 and 2014. But plans for the world’s largest solar power plant, a 4,000-megawatt project in the midst of the Thar Desert in the west, have stalled over concerns about the risks to flamingoes and other migratory birds that winter at the wetlands nearby.

And even as it achieves a large ramp-up of solar and wind power, India needs additional investment in power stations and lines to distribute that power, according to Bridge to India, a solar energy-focused advisory group. In a recent report, Bridge to India argued that the country needed solar “beehives”—photovoltaic panels on millions of residential rooftops—in addition to its “solar elephants.”

Some organizations have been working to advance this smaller-scale approach. The environmental group Greenpeace recently led a solar-powered electrification project in the village of Dharnai. The 100-kilowatt micro-grid is powering 450 homes in the central state of Bihar.

Abhishek Pratap, senior energy campaigner with Greenpeace, said that small-scale renewables are a quicker way of addressing rural energy needs in India than building large coal plants.

“These kinds of projects, where energy is consumed close to where it’s generated, are very energy efficient,” Pratap said, “and should be much more common than they are in India.”

A Need to Be More Ambitious?

Modi’s government formalized its support for renewables with the annual budget it released in July, allotting funds for “green energy corridors” that are meant to address chronic issues with transmitting energy from renewable sources to market. The budget also funds the development of small solar parks along canals and solar-powered pumps for farms, among other sustainability initiatives.

But in some respects, the budget’s scale was modest: It allotted funding for large solar power projects in just 4 of India’s 29 states. Bhushan of the Center for Science and Environment said this money might have been better spent setting up 20,000 mini-solar plants that together could provide electricity to 40 to 50 million households in rural India.

Bhushan said the budget offered merely a “symbolic” commitment to renewables. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen more mentions of renewable energy” in a government budget, Bhushan said, and Modi did increase funding for renewables by 25 percent over the last leadership. “But this budget still lacks ambition in terms of the amount of funding it provides.”

“We need a tenfold increase in investment in new and renewable energy and a long-term plan if we want to put a dent in our consumption of coal and oil,” said Bhushan.

Renewables other than hydroelectric—wind, solar, geothermal, and biomass—currently account for 13 percent of India total electric-generation capacity, more than twice as high a proportion as in the United States. But in practice they contribute less to the power grid because of a lack of transmission capacity and a lack of incentives for companies to purchase solar and wind power.

Renewables are bound to increase over the next five years, said Ashwin Gambhir, a renewable energy policy analyst at Prayas Energy Group, a nonprofit group dedicated to optimizing the country’s energy resources, “but expanding access to electricity will only be possible by relying on conventional power sources and extending the central [power] grid.”

Despite the multi-pronged effort to boost renewables in India, energy minister Goyal has made it clear that coal will not be going away. In a synopsis of his government’s first hundred days, he touted record growth in coal-fired electricity generation in recent months and set new targets for coal exploration and production. He called the country’s gap in electricity access an “abomination.”

Goyal’s comments seem to confirm that India is far more focused on fixing its coal industry than on phasing it out. There is much to fix: Although India is the world’s third largest producer and consumer of coal, chronic supply and transport problems have left the country struggling to meet growing electricity demand.

To move its domestic coal, India relies on a few overburdened rail lines that chug along from production centers in the east of the country to consumption centers in the west and south. Because of that bottleneck and other factors, notably a continually mounting demand, government-owned Coal India—which produces 80 percent of India’s supply—has consistently fallen short of production targets.

That has left power plants chronically short of coal stocks and producing less electricity than they’re capable of. The companies also grapple with power losses on the grid that are well upwards of 21 percent, among the highest in the world, and that are largely due to widespread theft by people tapping into power lines.

The country is plagued by blackouts, most notably the massive outage that affected more than 600 million people in 2012. More recently, a system failure left half of Mumbai in the dark for several hours.

The sluggish production, foundering railroad projects, and high transport costs have contributed to driving up the country’s reliance on imported coal from Indonesia and South Africa. As the U.S. Energy Information Administration pointed out recently, the country’s net coal import dependency soared “from practically nothing in 1990 to nearly 23 percent in 2012.”

The bottom line, analysts such as Bhushan and Gambhir agree, is that the urgent demand for electric power production in India looks set to lead, at least in the short term, to a large increase in coal-powered electricity, and a corresponding increase of coal imports.

More Funding Needed for Renewables

Even as India ramps up renewable energy production and distribution capacity, it needs to ensure that state-owned electricity companies actually purchase that energy. The state of Tamil Nadu, for example, has about 40 percent of the country’s installed capacity for wind power. It’s actually less expensive there than coal power. But state-owned distribution companies often don’t buy much of it for a variety of reasons—including their fear that the rise and fall of winds, which they lack the ability to forecast well, will destabilize the grid.

Since 2010, India has set mandatory minimums for how much renewable energy distribution companies and large power consumers must purchase. The national government has set a minimum purchase goal of 15 percent by 2020, but as Gambhir has pointed out, it’s the state regulatory commissions that actually carry out the policy—and many of them have been decreasing their targets lately. What’s more, companies are not penalized for failing to meet them.

India’s government has set out to raise clean energy funds by taxing coal, but it’s not clear that those funds are being used to promote renewable energy initiatives.

In June, the Economic Times reported that only one percent of the collected tax funds had been allocated to the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy during the previous government’s term. Now Modi’s government has announced its intention to divert it to its own non-clean energy related flagship programs, like a plan to clean up the heavily polluted River Ganges.

“This fund is not being used as it’s intended,” said Jasmeet Khurana, an analyst at Bridge to India. “Ambitious targets can only be realized if funds are made available for research and development. Only then can the renewable energy industry move from being incentives-driven to market-driven.”

Until then, coal will remain a significant portion of India’s energy mix, Khurana said: “No projection says it’ll go below 55 to 58 percent in the next ten years.”