The developers could eventually propose another solar project at the same site, which is about 60 miles east of Indio. But their decision to withdraw the controversial Palen proposal ends any chance of development in the foreseeable future.

BrightSource senior vice president Joe Desmond said the developers chose to withdraw their application in part because the project was unlikely to be completed by December 2016, meaning it wouldn’t qualify for a 30 percent investment tax credit that expires at the end of that year. Construction was slated to last 28 months — well into 2017, even if the California Energy Commission had granted final approval next month.

Desmond said banks probably wouldn’t have been willing to finance Palen’s construction, considering it was unlikely to qualify for the 30 percent tax credit.

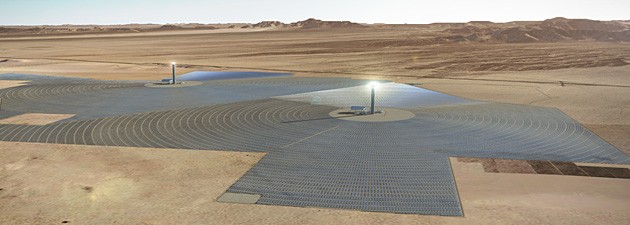

Palen would have taken advantage of power tower technology, which uses thousands of mirrors to direct sunlight at massive solar towers. Only one other large-scale solar tower development — BrightSource’s 377-megawatt Ivanpah project in San Bernardino County — has come online in the United States.

“We are committed to bringing projects to the market that follow sound and responsible environmental measures to ensure all impacts are avoided, minimized or compensated for properly,” he said in the statement.

BrightSource and Abengoa could theoretically build a solar trough project without receiving additional approval from the California Energy Commission. Solar Millennium originally planned to build Palen with solar trough technology — a proposal the energy commission greenlighted before Solar Millennium went bankrupt. The project was picked up by BrightSource and Abengoa, which asked the commission to approve a solar tower facility instead.

“We believe concentrating solar power, and specifically tower technology with thermal energy storage, can play a key role in helping California achieve its clean energy goals by providing the necessary flexibility needed to help maintain grid reliability,” he said in a statement.

Still, the Palen withdrawal does not bode well for the future of power tower technology. It would have been just the second large-scale solar tower facility to come online in the United States, and BrightSource had asked regulators to put its application for a similar proposal — the 540-megawatt Sonoran West project — on hold, pending the resolution of Palen’s review process. It’s unclear whether BrightSource will still attempt to develop Sonoran West.

The energy commission’s preliminary decision on Palen — which was written by the two commissioners overseeing the project’s review process, Karen Douglas and David Hochschild — was not final, but it was unlikely to be overturned by the full commission. The commission had planned to hold a conference Oct. 6 to solicit public input, before making a final decision Oct. 29.

Desmond said the developers chose to announce the Palen withdrawal now, rather than later, so that stakeholders wouldn’t have to “expend time and energy” discussing the project over the next month. He declined to say how longer BrightSource and Abengoa have been considering dropping the project.

He also hinted that the California Energy Commission’s decision to approve just one solar tower — rather than two, as the developers had proposed — might have contributed to the withdrawal.

“After carefully reviewing the proposed decision recommending approval of one tower, we determined it would be in the best interest of all parties to bring forward a project that would better meet the needs of the market and energy consumers,” Desmond said in a prepared statement.

Each of Palen’s solar towers would have topped out at 750 feet and generated 250 megawatts of electricity. In their preliminary approval earlier this month, energy commissioners Douglas and Hochschild wrote that approving just one tower “feasibly lessens most of the … significant impacts while attaining most of the project’s objectives.”

Whether BrightSource and Abengoa eventually propose another project could depend on whether Congress extends or modifies the 30 percent investment tax credit for renewable energy projects, which is slated to drop to 10 percent starting in 2017. The solar industry has been pushing Congress to modify the language of the tax credit, so that solar projects with some electricity online by the end of 2016 qualify — rather than just projects that are fully online.

“Right now, the solar energy industry and others are working hard to change that,” Desmond said.

Palen overcame long odds in earning the California Energy Commission’s preliminary approval. Last December, Douglas and Hochschild recommended that the commission reject the project, citing “significant environmental impacts that cannot be mitigated.”

But BrightSource and Abengoa asked for a second chance to make their case, and they eventually convinced the commissioners to change their minds. While the developers didn’t change much about their proposal, they successfully argued that Palen would be able to incorporate thermal energy storage at some point in the future.

Developing storage capacity is a top priority for regulators and solar companies alike, due to this intermittent nature of solar power and the problems this can pose for integrating solar power into the energy grid. Douglas and Hochschild noted in their preliminary approval that power tower technology “allows for more efficient and more cost effective energy storage” than other concentrated solar power technologies, due to its higher operating temperatures.

But while they successfully made their case to the energy commission, BrightSource and Abengoa ultimately decided they couldn’t go forward with the project.