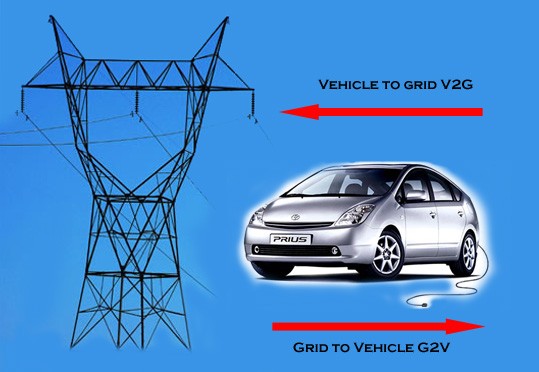

Imagine having the car you drive doing double duty as a part of a mini power plant, taking power from and giving it to an electric grid, and getting paid for the service.

Willett Kempton, professor in the College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment, shared his vision for grid-integrated vehicles with retired faculty members during a luncheon meeting of the University of Delaware Association of Retired Faculty, held Tuesday, Oct. 14, in Clayton Hall.

The inventor of innovative grid-integrated vehicle technology, Kempton also serves as research director for the University’s Center for Carbon-free Power Integration.

During his presentation, “Grid-Integrated Electric Vehicles: Enough Storage for Large-Scale Variable Generation,” Kempton noted that there is a very rapid shift toward a new form of power generation based primarily on wind and solar energy production.

“I want to frame the idea for you, that the grid is great for adjusting to fluctuations in power, and to talk about electric vehicles in the context of the expanding generation of wind and solar power,” Kempton said. “I’m developing storage, but in the interest of full disclosure, let me say that wind and solar generated electricity don’t really need storage, at least for a while.”

Currently, as demands on electricity systems fluctuate, large generators ramp up and down quickly to adjust for the changes and to balance electricity supply and demand, Kempton said.

“All power generation is intermittent, and in that respect wind and solar are not any different than coal or natural gas,” Kempton said. “A typical coal and natural gas or coal power plant in commercial operation has an unscheduled outage rate of about five percent. If we had to have all electric power generation 100 percent reliable, we wouldn’t be able to keep the lights on.”

Kempton noted that electric power plants are connected to a grid to make up for loss of generation due to an outage at an individual power plant.

Wind and solar sources also comprise a large and growing segment of power production, Kempton said.

“People believe that if we get wind and solar power, this is going to lead to austerity, and that they will not be able and use all of their electric appliances,” Kempton said. “The truth is, we will have a lot more energy by moving from fossil fuel to wind and solar power.”

Because variable generation from wind and solar sources fluctuates according to natural forces, a system that matches variable generation to our consumption of power, the “load,” needs to be developed, Kempton said.

“The cheapest way is through transmission, rather than storage,” Kempton said. “If you disperse generators and connect them by transmission, you create a pool of resources and enlarge the area managed by a single entity in technical terms of balancing load.”

Because the management of any projected increase in solar power generation will require more storage, vehicle-to-grid technology offers an important new tool for stabilizing the nation’s electricity supply and developing energy independence, Kempton said.

“At times, there really isn’t enough electricity on the system, and this is when operators would like to take electricity out of storage devices and put it back on the electric grid,” Kempton said. “There is a lot of inherent storage available in electric vehicles, and batteries are the cheapest and most versatile way to store electricity.”

The electric vehicle-to-grid technology system developed at UD responds faster to fluctuating energy needs, costs less to operate and doesn’t burn fuel or create pollution, Kempton said.

“If a person buys an electric vehicle, they usually drive it about an hour each day. The vehicle is idle for the remaining 23 hours,” Kempton said. “We are going to use this electric storage device for the other 23 hours, and we will pay them for the use of it.”

Kempton said that electric vehicle-to-grid systems developed at UD includes a vehicle smart link in the car that controls charging and reports back to the server.

“The second component, the electric vehicle supply equipment developed by the College of Engineering’s Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, goes in the car and monitors what is going on with the car and the batteries, and communicates that information to the charging station and ultimately to the aggregator,” Kempton said. “The aggregator (server) component provides real time operation, talking to the cars and the grid operator and making bids on power markets while meeting legal requirements.”

Electric vehicles used on the UD campus are modified and tested in a laboratory located on the Science, Technology and Advanced Research (STAR) Campus, Kempton said.

“The electric grid is all about being located on the ground and in buildings,” Kempton said. “The charging station has to know where the car is and which wires that box is connected to for a variety of reasons, including safety concerns.”

Kempton said that the electric vehicle-to-grid project is participating in the market and following all compliance and test requirements.

“The conclusion here is that the technology works,” Kempton said. “This could be a self-sustaining business.

Article by Jerry Rhodes