There are two things you notice as you travel through the vast expanses of South Australia: wheat and wind.

The former sustains the economy. The latter provides the power.

There are huge golden wheat farms stretching for hundreds of kilometres. Sprouting out of many of these fields are huge wind turbines, 21st Century windmills relentlessly churning through the air.

Up close, each turbine is massive, with a wingspan of more than 80m (262ft). If you laid one flat on the ground, it would be too big to fit on a full-size football pitch.

Each turbine provides enough electricity to power 1,000 homes.

Australia doesn’t often get credit for its environment policy but when it comes to wind power, the state of South Australia is among the world’s leaders.

The Australian Energy Market Operator says wind and solar power accounted for around 27% of South Australia’s energy in 2012-13.

But in the past year, several new wind farms have gone on stream, meaning on an average day wind power now accounts for almost 40% of South Australia’s delivered energy, according to Gus Nathan, professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Adelaide’s Centre for Energy Technology.

“On a good day, when the wind’s really blowing, it can account for all of the energy in our network,” he says.

Strong potential

South Australia is right up there with environmentally friendly Denmark, the world leader in wind power, with 39.1% of electricity production generated by wind in 2014, according to the Danish government.

However, the rest of Australia has not followed this lead, producing only about 4% of its power from wind, according to Australia’s Renewable Energy Agency.

Investments in large-scale wind, solar and other clean energy sources dived 88% in 2014 to A$240m ($196m, £128), the lowest level since 2002, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

The slump in investment pushed Australia’s ranking among investors in large-scale renewable energy below much poorer nations such as Panama, Sri Lanka and Myanmar, as confidence in the government’s policies for the sector evaporated, Bloomberg reported.

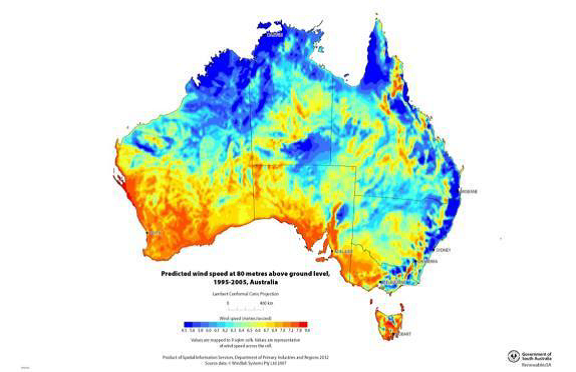

South Australia benefits from a very high proportion of high quality wind resource, says Prof Nathan “and that’s basically because we have the wind blowing off the Antarctic coming up over the Southern Ocean”.

“But in addition, the policy drivers in South Australia are what have driven it. There’s been much higher targets here for renewable energy,” he adds.

The state is not far off achieving its target of producing half of its electricity from renewable energy by 2025.

World-class wind resources and a streamlined planning and regulatory process have made it easier for companies to invest in wind than in other parts of Australia.

But the Renewable Energy Target at a national level has been set at 41,000 gigawatt hours (GWh) by 2020, estimated to represent between 20% and 27% of Australia’s energy use, depending on actual energy consumption.

That figure was introduced by the previous Labor government and offers financial incentives to companies that invest in wind and solar power.

Mixed messages

The current conservative coalition government led by Prime Minister Tony Abbott wants to reduce the target.

Mr Abbott says he supports renewable energy but doesn’t want measures that increase electricity prices and pass unnecessary costs to the public.

His treasurer, Joe Hockey, went further, describing windfarms as “utterly offensive” and “a blight on the landscape”.

In comparison, last year Mr Abbott described coal – a major Australian export – as “good for humanity”.

Under current federal government policies, wind power, although hugely successful in South Australia, faces an uncertain future.

Energy companies such as Trust Power, which operates wind farms in Australia and New Zealand, want a stable energy policy.

“I guess what we see is the current government struggling to provide that,” says Ian Lees, Trust Power’s engineering manager.

“We’d like to see some indication that renewables are a favourable option to invest in. Unless there’s a stable economic platform for development then there will be no development.”

Prof Nathan says a large number of wind farm projects that have been approved by the South Australian government are on hold because of the uncertain policy environment.

“There’s no incentive for people to install new generating capacity of any kind. If the renewable target were increased, that would provide a mechanism to drive investment in renewable energy. Without that, it’s unlikely to happen.”