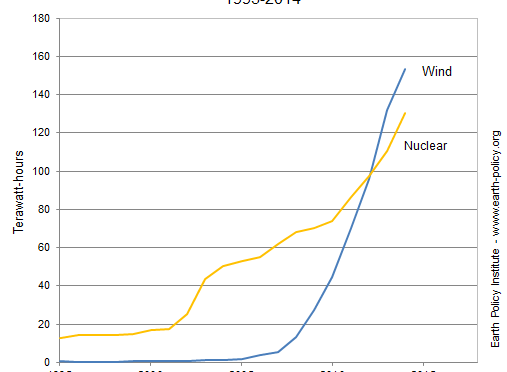

China, the country that is building more nuclear reactors than any other, continued to get more electricity from the wind than from nuclear power plants in 2014. This came despite below-average wind speeds for the year. The electricity generated by China’s wind farms in 2014—16 percent more than the year before—could power more than 110 million Chinese homes.

China added a world record 23 gigawatts of new wind power capacity in 2014, for a cumulative installed capacity of nearly 115 gigawatts (1 gigawatt = 1,000 megawatts). Some 84 percent of this total—or 96 gigawatts—is connected to the grid, sending carbon-free electricity to consumers.

As China’s wind power installations took off in the mid-2000s, electric grid and transmission infrastructure expansion could not keep pace. But the situation is improving: China is building the world’s largest ultra-high-voltage transmission system, which is connecting remote, wind-rich northern and western provinces to the more populous central and eastern ones. At the same time, the government is providing incentives for wind farm development in less-windy areas nearer to population centers. Advances in wind power technology can allow greater capture of energy in spots without the strongest wind resources.

China’s wind power goal is to have 200 gigawatts connected to the grid by 2020. According to China’s National Energy Administration, the country has some 77 gigawatts of wind capacity now under construction, bringing this goal that much closer to being realized. Efforts to bolster the grid and connect more turbines are reducing the amount of potential wind generation lost each year due to curtailment, when turbines must stop producing because the grid cannot take on any more electricity. Since 2012, the rate of this curtailment at China’s wind farms has dropped by more than half; however, further improvements are still needed.

Even as it pursues the world’s most ambitious wind power goal, China also undeniably has the world’s most aggressive nuclear construction program, currently accounting for 25 of the 68 reactors being built worldwide. Six reactors totaling 6 gigawatts of capacity went online in China in 2013 and 2014. Another reactor connected to the grid in January 2015, bringing national nuclear capacity to 20 gigawatts at 24 reactors. But to meet the government’s nuclear target of 58 gigawatts by 2020, China will not only need to complete the reactors now under construction—most of which are behind schedule—it will need to start and finish another dozen or so by then.

Several factors stack the odds against China meeting its nuclear power goal. After a massive earthquake and tsunami induced the 2011 nuclear meltdown in Fukushima, Japan, the Chinese government suspended approvals for new reactors as it conducted safety reviews of those operating and under construction at the time. The moratorium was lifted in late 2012, yet for more than two years no new reactors received permission to build. In February 2015, a nuclear plant in northeastern Liaoning province reportedly got the go-ahead for a two-reactor expansion. Once construction begins, it typically takes six years to complete a reactor in China (compared with one year or less for the average wind farm).

Further complicating China’s nuclear picture is that suitable real estate for new reactors along the coast—with ready access to cooling water—is in increasingly short supply. Following the Fukushima disaster, public opposition to reactors in China’s earthquake-prone inland provinces grew, prompting officials to put off consideration of proposed reactors in non-coastal provinces until 2015 at the earliest. Regardless of when the government decides to begin approving inland reactors, nuclear developers will face dwindling freshwater resources.

Perhaps the biggest question facing the future of nuclear power in China is the fate of the 1-gigawatt Sanmen reactor under construction in Zhejiang province. Designed by Westinghouse, this is a “Generation III” reactor billed as much safer than previous nuclear technologies, due to its earthquake and flood resistance features and its ability to continue cooling in the event of a prolonged loss of power. Sanmen is both the basis for Chinese-designed third generation reactors and a test case for the technology closely watched worldwide.

When construction got under way at Sanmen in 2009, completion was projected by the end of 2013. Blaming increased safety concerns and design changes post-Fukushima, the developer pushed this date back to 2015. Then in January 2015, the chief engineer of China’s State Nuclear Power Technology Corp., Wang Zhongtang, announced that Sanmen would not generate electricity until 2016, if that soon. As the project runs further behind schedule and goes further over-budget, more doubt is cast on the design’s ability to catalyze faster nuclear power growth in China.

China’s energy landscape is changing rapidly. Consumption of coal, which supplies about 75 percent of Chinese electricity, dropped nearly 3 percent in 2014, according to official data from China’s National Bureau of Statistics. Meanwhile, in addition to the impressive growth in wind power, China is quickly expanding its solar generating capacity. With 28 gigawatts by the end of 2014 and plans for another 15 gigawatts in 2015, China may overtake Germany for the top solar spot in a matter of months. As China looks to energy solutions to reduce the air pollution choking its cities, to conserve water, and to rein in its carbon emissions, it is becoming clear that renewables offer a more expeditious path than nuclear power does.

http://www.earth-policy.org