Wind power accounted for 23 percent of new capacity, with coal taking a share of less than 1 percent.

California saw three concentrated solar power plants come fully online in 2014: the Genesis project in Riverside County and the Ivanpah and Mojave projects in San Bernardino County, collectively accounting for another 767 megawatts of new generating capacity. Instead of traditional solar panels, concentrated solar projects use sunlight to heat water or another liquid, ultimately creating steam that can be used to turn turbines and generate electricity.

But even though 2014 was a record-breaking year for the industry, there are storm clouds in the distance, solar advocates say. A federal investment tax credit for solar power is scheduled to drop from 30 percent to 10 percent at the end of 2016, which could slow the industry’s rapid growth.

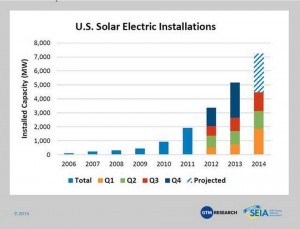

More than 6,200 megawatts of traditional solar energy capacity came online in the United States in 2014 — 30 percent more than the previous year, and enough to power more than one million homes, according to a report released earlier this week by GTM Research and the Solar Energy Industries Association. California was responsible for more than half of that growth, with about 3,550 megawatts.

The past two years were something of a “coming out part for the solar industry,” said Cory Honeyman, a solar analyst for GTM Research, a clean-tech consulting firm. While tax incentives and renewable energy mandates are still critical to the market, he said, the costs of solar fell substantially in 2013 and 2014.

“There really was this growing up process over the past 24 months, where I think a lot of the drivers of growth really expanded beyond regulatory-driven reasons,” Honeyman said.

For at least the eighth year in a row, California led the nation in new solar capacity, installing more than three times as much solar as it did in 2012. California ran laps around the other 49 states, installing nine times more capacity than its closest competitor, North Carolina.

California’s rooftop solar industry has also experienced “unprecedented geographic diversification,” the report notes. Last year, 73 cities in Southern California installed at least one megawatt of rooftop solar — up from 56 cities in 2013, and just 22 cities in 2012. Six of those 73 cities were in the Coachella Valley, although Honeyman said confidentially agreements prevented him from naming those cities.

In a separate report earlier this year, the Solar Foundation reported that the solar industry employed nearly 55,000 people in California in 2014.

The state’s booming solar industry is a result of several factors: abundant sunlight, plenty of open space to build large-scale projects, and legal mandates intended to limit California’s contribution to climate change. The state’s major utilities are on track to buy 33 percent of their electricity from renewable sources by 2020, as required by state law, and policymakers are discussing a new 50 percent mandate.

The potential impact of that change is reflected in Tuesday’s report, which projects an 84 percent drop in large-scale solar installations between 2016 and 2017. Still, the report projects that the industry would recover even without the 30 percent tax credit, with overall solar photovoltaic installations coming close to 2016 levels by 2020.

Ken Johnson, a spokesman for the Solar Energy Industry Association, said several factors bode well for solar: falling prices, the potential for new renewable energy mandates in states like California, and President Barack Obama’s “Clean Power Plan” to curb planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions. Still, the solar association plans to lobby Congress to extend the 30 percent tax credit, without which 2017 will be “a very difficult year” for the industry, Johnson said.

“In the end, no one knows how for sure this is going to shake out,” Johnson said in an email, referring to the future of the solar industry. “It’s a real crapshoot — and markets hate uncertainty.”

Advocates say concentrated solar power has a major advantage over traditional solar panels: the ability to store energy, and thus generate electricity even after the sun goes down.

“The challenges still come with how much it actually still costs to develop (concentrated solar) projects,” Honeyman said. “There have to be a certain amount of cost reductions.”