Concentrated solar power, in which reflective troughs heat up water that is then fed to heat exchangers and turbines to produce electricity, could play a key role in India’s energy future.

In central Karnataka state, 120 miles north of Bangalore, the lush jungle of India’s west coast gives way to dry scrubland. Sunflowers, onions, chilis, and groundnuts grow in parched fields. In scattered, populous villages, concrete buildings alternate with ramshackle thatched huts. Cows nose through the garbage, and wooden carts drawn by horned oxen crowd the streets. Rough brick-producing factories belch black smoke into the air. Much of the scene appears as it did a century ago. But in a walled compound just beyond the town of Challakere sits an installation that could hold one of the keys to India’s energy future.

The project, run by the Bangalore-based Indian Institute of Science (known as IISC), is a test array for concentrated solar power. Rows of shallow parabolic troughs, made of specially coated aluminum, stretch for more than the length of two and a half football fields. Above them are water pipes set to catch sunlight reflected from the troughs. When the project begins operation in a few weeks, the water in the pipes will be heated to 200 °C (392 °F); the hot water will go to a heat exchanger attached to a small turbine that will produce 100 kilowatts of electricity.

A part of the Solar Energy Research Institute for India and the United States (SERIIUS), this small solar array will be used to test various reflective materials and heat-transfer fluids (including, for instance, molten salt in addition to water) from multiple manufacturers. Dozens of small wireless sensors will collect data and send it via the Internet to a dashboard at IISC, where it can be analyzed and catalogued. The objective, says Praveen Ramamurthy, a professor of materials engineering at IISC, is to find the combinations of components that best suit conditions in India, which under the National Solar Mission of Prime Minister Narendra Modi is poised to become one of the world’s largest solar markets in the next seven years.

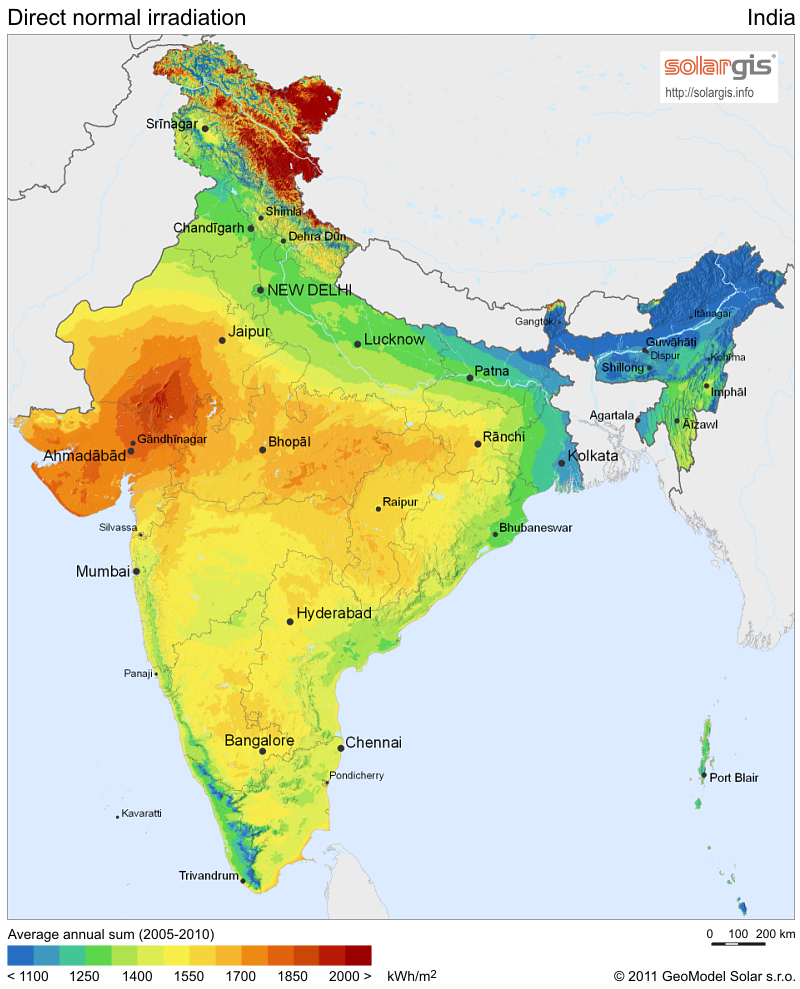

The Indian subcontinent, as has often been noted, is a world unto itself, encompassing the rainforests of Assam, the deserts of Rajasthan, and the Himalayan plateaus of Ladakh. Finding solar panels that will stand up to these extreme conditions will be critical to Modi’s goal of building 100 gigawatts of solar capacity by 2022. “Nobody is testing for the aging [of solar equipment] in India,” says Ramamurthy. “We get solar panels, but they’re certified for moderate climates in the U.S. and Europe, and we just adapt.”

India’s solar mission is important not only to India but to the entire world. The world’s third-largest emitter of greenhouse gases, India is an energy-starved, coal-dependent country, where more than 300 million people, according to official estimates, live without electricity and millions more have only spotty service from the grid. Modi has pledged to create dozens of “ultra mega solar power parks,” of 500 megawatts and above, to feed power to the grid, even as the National Institute for Rural Development embarks on a program to bring rooftop solar panels to thousands of India’s impoverished villages. Piyush Goyal, the minister of power, has said that the government’s energy policies will reduce annual carbon dioxide emissions by 550 million tons. Whether India can industrialize and provide universal electricity access while reining in greenhouse-gas emissions will help determine whether the world can avoid catastrophic climate change.

The Challakere test array will eventually include solar photovoltaic installations, as well as concentrated solar. Ramamurthy’s own research focuses on developing polymers to encapsulate solar panels and seal them against high temperatures and humidity, which tend to rot the adhesives that hold conventional solar panels together. Dust and degradation are also major problems in India. And then there are the monkeys.

Like many places in India, IISC’s leafy Bangalore campus abounds with tribes of monkeys that like to lick the dew off solar panels and chew the electrical cables. Various methods have been tried to drive them off, but so far none have worked, including an ultrasonic monkey repeller that actually seems to attract the primates. “We’ve tried giving them food to lure them away, but they just sit there,” says an exasperated Ramamurthy. “I don’t know what to do.”

While solar PV is expected to provide the majority of solar power generation in India, concentrated solar is also of keen interest, as it can be put to a variety of non-electricity applications. Those brick factories in Karnataka, for instance, are mostly illegal, and they bake the bricks using firewood. That causes deforestation and heavy emissions of carbon dioxide. Using concentrated solar power to bake bricks would be a huge boon to the environment.

In other words, the work being carried out at Challakere will help India, whose energy sector in many ways has progressed little since the 1960s, leapfrog its way to a 21st-century solar industry.

By Richard Martin

termosolar, Concentrated Solar Power, Concentrating Solar Power, CSP, Concentrated Solar Thermal Power, solar power, solar energy, India, Karnataka, Indian Institute of Science,