As Europe’s wind energy production rises dramatically, offshore turbines are proliferating from the Irish Sea to the Baltic Sea. It’s all part of the European Union’s strong push away from fossil fuels and toward renewables.

On a sunny October morning, our boat passes the run-down relicts of Liverpool’s maritime past and heads down the river Mersey and into the Irish Sea. As we steam offshore, I see in the distance a cluster of tall structures that soon reveal themselves to be towers of a wind turbine array. Arriving at the wind farm, six miles offshore, the turbines rise as high as 650 feet, taller than the tallest church in the world. Each of the turbines’ three shiny metallic rotor blades is nearly 300 feet long.

“A single rotation of an eight-megawatt turbine will cover the daily electricity consumption of an average British household,” says Benj Sykes,vice president of DONG Energy Wind Power, the company that is constructing and co-owns this wind project, as the boat rocks in five-foot swells.

Workers have been busy at the Burbo Bank Extension, named for this patch of the Irish Sea, since June, using gigantic cranes to drive foundations 50 feet into the sea floor. With a design capacity of eight megawatts each, the 32 turbines are the most powerful ever installed at a commercial offshore wind farm. Once the rotors start spinning later this year, the Burbo Bank wind farm will be able to power 230,000 households — enough to run Liverpool city, with its 466,000 inhabitants.

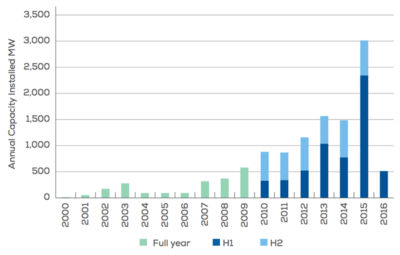

In Europe, offshore wind farms like the one at Burbo Bank are undergoing a boom. While still significantly outnumbered by wind farms on land, the importance of wind farms at sea has grown dramatically in the past several years. Until 2011, between 5 and 10 percent of newly installed wind energy capacity in Europe was offshore. Last year, almost every third new wind turbine went up offshore. That growth has helped boost the share of wind energy in the European Union’s electricity supply from 2 percent in the year 2000 to 12 percent today, according to Wind Europe, a business advocacy group.

New investments for offshore projects totaled $15.5 billion in the first half of 2016 alone, according to Wind Europe, and newly installed offshore wind energy capacity will double to 3.7 gigawatts this year compared to 2015. More than 3,300 grid-connected turbines now exist in the North Sea, the Baltic Sea, and the Irish Sea, and 114 new wind turbines were linked to the grid in European waters in the first half of this year alone. This is in stark contrast to the U.S. and Asia, where offshore wind use is only just getting started.

The offshore wind boom is part of a wider move from fossil fuels to renewable energy across the European Union. The overall share of renewable electricity sources in the EU — hydropower, wind, solar, biomass, and geothermal — has gone up from about 15 percent in 2004 to roughly 33 percent in 2014, according to data from Eurostat and Entso-E, the association of grid operators. Along with solar photovoltaic power, wind energy is driving this expansion. Newly installed wind energy capacity amounted to 13 gigawatts in 2015, twice as much as newly installed fossil fuel and nuclear capacity combined. Wind Europe claims that all European wind turbines taken together can now generate enough electricity for 87 million households.

This is not only a result of government subsidies and incentives, but also of dramatically reduced production costs for wind energy. The price for a megawatt hour is now between 50 and 96 Euros for onshore wind and 73 to 140 Euros for offshore wind, compared to around 65 to 70 Euros for gas and coal. Electricity generated from onshore wind farms is now the cheapest among newly installed power sources in the U.K. and many other countries. If environmental costs are considered, the picture looks even more favorable for wind power.

Annual installed offshore wind capacity in Europe, measured in megawatts. H1 and H2 represent installation in the first and second half of each year. Wind Europe

Germany now meets one-third of its electricity demand with renewable energy, Denmark 42 percent, and Scotland as much as 58 percent. On some sunny or very windy days, renewables can now fully supply the electricity demand in these countries.

The picture isn’t entirely rosy, though. The European wind industry says that grid and storage infrastructure hasn’t expanded fast enough to soak up surplus wind energy, and that the fossil fuel and nuclear industries are trying to sabotage what is called Energiewende, Germany’s transition from coal and nuclear power to renewable energy. The wind energy boom, with its recurrent surges of surplus energy, has led to a dramatic decline in electricity prices in spot market trading at the European Electricity Exchange, with the price per kilowatt hour falling by as much as 50 percent in the last five years. With preferential treatment from EU governments, wind energy is now outcompeting coal-fired power plants, posing major challenges for utilities heavily invested in fossil fuels.

Out in the Irish Sea, however, DONG Energy’s Sykes shows no mercy for the fossil fuel industry. “Wind power on land is becoming the cheapest form of newly installed electricity capacity,” he says. “And even out here at sea, we can’t say anymore that there are technical hurdles.”

DONG Energy — co-owned by the Danish state, Goldman Sachs, shareholders, and two pension funds — is the European leader in offshore wind projects, surpassing competing companies like RWE Innogy, Iberdrola and Northland Power. Its full name — Danish Oil and Natural Gas — reflects its less-than-green history. Sykes personifies this transition. Before he joined DONG in 2012, the Cambridge University-trained geologist spent almost 20 years exploring for oil and gas reserves for large fossil fuel companies like Shell and the Hess Corporation. He says he left the fossil fuel industry and joined the wind business in part because of criticism from his environmentally minded children.

The reasons for the European offshore wind energy boom are manifold: For one, European governments and the EU as a whole have supported wind projects with favorable incentives as part of their CO2 reduction goals. In addition, the cost per megawatt hour has dropped by about 50 percent in the last few years alone for many projects, with a record low of $81 for DONG’s Borssele 1 and 2 projects — two soon-to-be-built wind farms off the Dutch coast. That’s compared to $155 for offshore wind installations just a few years ago.

Costs have fallen because production of wind turbines has become more industrialized and standardized and the size of turbines and generators has increased, thus harvesting wind more efficiently. In addition, offshore wind projects can reap the stronger winds found at sea, compared to land, and are far less likely to attract protests by neighbors who often object to their presence. There are also environmental concerns about how these industrial facilities affect sea birds and marine life, but so far this has not limited the expansion of offshore wind.

Benj Sykes, vice president of DONG Energy Wind Power, which is constructing new 8 megawatt turbines in the Irish Sea. Christian Schwägerl/Yale e360 & DONG Energy

Sykes’ colleagues in the wind energy industry are more cautious about the future. At the WindEurope Summit in Hamburg last month, where several hundred industry representatives gathered, Dickson, chief executive officer of Wind Europe, said that European political and administrative leaders hadn’t come up with detailed plans of how each nation will achieve the goal to generate 27 percent of all energy (including transport and heat) from renewable sources by 2030, which would mean renewables would have to generate 47 percent of the continent’s electricity.

Maroš Šef?ovi?, vice president of the European Commission, the union’s administrative body, said that while Europe has created 300,000 jobs in the wind industry, China, the U.S., and India are catching up fast.

Sigmar Gabriel, Germany’s former environment minister turned economics and energy minister, said it was time for the continent’s wind industry to rely less on subsidies and incentives and become more independent. “After years of guaranteed prices and feed-in tariffs,” Gabriel told the meeting, “the wind industry doesn’t need a puppy license any more.”

Analysts say that the main obstacle to further rapid expansion of Europe’s wind sector, offshore in particular, stems largely from political failure. European governments have yet to build up the new electricity grid infrastructure that could transport large quantities of renewable energy from often sparsely populated northern coastal areas to the industrial centers farther south. Germany, in particular, has not created favorable conditions for additional wind expansion. Despite being at the heart of Europe geographically and being a driving force in renewable advances, the country’s federal and state governments were not able so far to build long-promised north-south “power autobahns” to expand grid capacity and transport offshore wind to areas with heavy electricity consumption. Politicians have often given in to local opposition to new power lines, while putting cables underground, as is now envisaged in Germany, is costly and experiencing long delays.

This grid bottleneck means that in 2015 alone, 4,100 gigawatt hours of wind electricity — enough to power 1.2 million households — could not be transported through the grid, according to the German Federal Grid Agency. “What is lacking in particular is a smooth expansion of grid connections and grid capacity to take up the electricity we produce,” Dickson said at the wind energy summit. What he got from German vice chancellor Gabriel in response wasn’t a promise to speed up power line construction, but a policy statement on limiting newly installed capacity for offshore and onshore wind.

“In the past, our goal was maximum expansion and the motto was ‘the faster the better,’” said Gabriel. “But we have now reached limitations as the expansion of the grid system hasn’t kept pace.”

While in the past investors were able to simply add wind turbines to the grid and receive feed-in tariffs for their electricity, they now have to bid for a limited grid capacity.

A second obstacle is a lack of major storage sites for surplus wind energy. For many years now, European governments have pledged to support new storage technologies, such as large-scale batteries or using the growing network of electric cars for storage. Yet projects haven’t succeeded beyond pilot phases because of technological and economic challenges.

To long-term players in the field like Henrik Stiesdal, a Danish wind power pioneer and former chief technology officer of Siemens Wind power, the situation is ironic: “While there were warnings in the past that wind energy would never be able to meet demands, politicians are now confronted with its abundance,” he said. Stiesdal sees storage technologies and better grid integration as opportunities, rather than problems — wind energy’s “golden bullets.”

“Once these problems are solved, wind will be able to cover the greatest part of the world’s electricity needs,” he says. The Wind Europe business group says it could easily double the amount of wind electricity for EU consumption to almost 30 percent by the year 2030. The group argues that the recent ratification of the Paris Agreement on climate change means the EU will have to pursue a more ambitious energy transition.

A visit to DONG Energy’s Burbo Bank project demonstrates the rapid progress the industry has made from its modest beginnings in the 1990s. It will take engineers and workers just a few months to assemble a facility that will provide electricity for a quarter-million households.

Like Stiesdal, DONG’s Sykes sees a bright future for offshore wind. He expects no impact from the U.K.’s Brexit and notes that the Burbo Bank Extension is co-owned by an unlikely player in power production: the parent company of Lego, the toymaker. “Offshore is a reliable and increasingly cheap source of energy, with no lasting harm to the environment,” Sykes says. “It will soon be simply unbeatable.”

http://e360.yale.edu