Investment in new renewable energy is on course to total $2.6 trillion in the years from 2010 through the end of 2019, according to a study by BloombergNEF for the United Nations Environment Program and Frankfurt School’s UNEP Center published Thursday.

The boom in the capacity to generate electricity from low-carbon sources gives credibility to an effort by world leaders to slash climate-damaging greenhouse gases. Falling costs of wind and solar power plants is making more projects in new markets economically competitive with generation fed by fossil fuels.

“Investing in renewable energy is investing in a sustainable and profitable future, as the last decade of incredible growth in renewables has shown,” said Inger Andersen, executive director of UNEP. “It is clear that we need to rapidly step up the pace of the global switch to renewables if we are to meet international climate and development goals.”

The scale of investment going into clean energy represents a growing chunk of the money flowing into the power industry. Renewables such as wind, solar and hydro-electric plants will draw about $322 billion a year through 2025, according to separate forecasts from the International Energy Agency. That’s almost triple the $116 billion a year that will go into fossil fuel plants and about the same as what will be invested in power grids.

By far the biggest contributions to new investment have been made in solar and wind farms. Global solar power capacity increased by more than 2,500% in the decade, from 25 gigawatts at the beginning of 2010 to 663 gigawatts anticipated by the end of this year.

Still, the end of the decade showed some cracks. Funds moving into solar declined in some of the biggest markets in 2018 compared with the year prior.

The cost of renewable technologies has fallen precipitously over the last few years. That’s also helped make renewables less reliant on government support. BNEF’s data shows the levelized cost of electricity is down 81% for solar photovoltaics since 2009.

“Sharp falls in the cost of electricity from wind and solar over recent years have transformed the choice facing policy makers,” said Jon Moore, chief executive officer of BloombergNEF. “Now, in many countries around the world, either wind or solar is the cheapest option for electricity generation.”

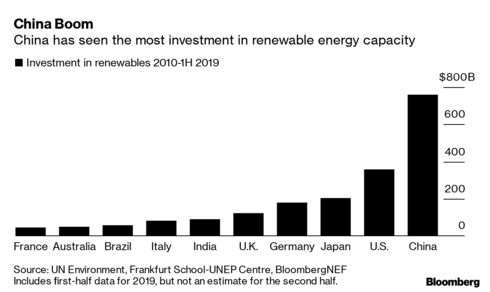

China has had by far the most investment in new renewable energy, making up nearly a third of the global total. The boom in solar hit a setback last year after the Chinese government announced restrictions on the number of new solar installations that would qualify for support. That led solar investment in China in the second half of 2018 to fall about 56% compared with the same period a year earlier.

Despite the significant investment, renewables still makes up a relatively small proportion of global power generation. China led the way in buying wind and solar plants but also poured money into new coal power generation units.

Many more renewable projects will come online in the coming decades. Wind and solar are set to contribute 48% of generation by 2050, according to BloombergNEF.

Overall, there’s been a net increase of 2.4 terawatts of installed capacity globally. While much of that has been from clean sources like wind, solar and hydro, a significant portion of that came from plants fired by coal and natural gas.

Europe and the U.S. have closed down coal plants, but that has been offset by an increase in Asia, especially in India. That’s helped to increase carbon emissions from the global power industry by at least 10% from the end of 2009 through 2019.