Advances in technology, improved economics, and broad political support are making wind power a formidable twenty-first century energy resource. Top-ranking Denmark draws 41% of its electricity from wind; Ireland follows with 28%; the European Union as a whole gets 14% of its power from wind.

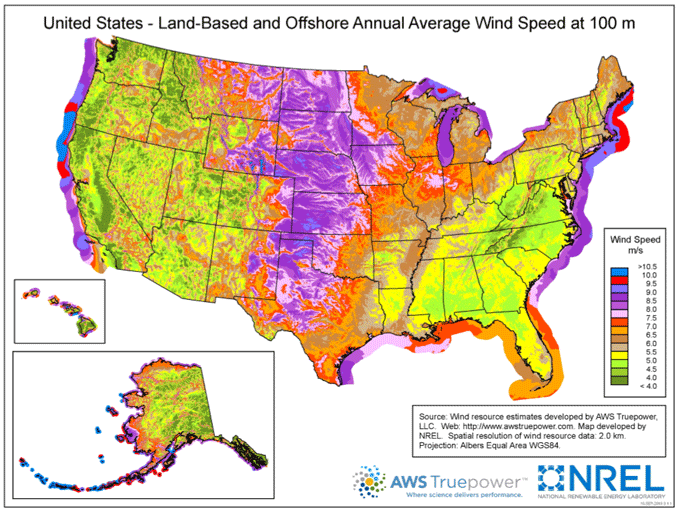

America’s wind farms currently produce 6.6% of the nation’s electricity. As a share of total power generation, that may sound relatively modest, but the U.S. ranks second only to China in the quantity of power-generating capacity that comes from wind. Moreover, the U.S. has scarcely begun to tap its vast wind power potential. On land, U.S. wind resources are capable of yielding about nine times the nation’s power needs. Offshore wind – wholly unexploited to date – could meet nearly twice the nation’s electricity demand.

Looking ahead, the Department of Energy has prepared a scenario for 35% wind reliance by 2050. While that level of wind generation sounds like major progress, it may be substantially less than is needed for renewable energy resources to be the primary drivers of a net-zero carbon U.S. economy.

Wind power’s evolution

Wind power has served various purposes in America since colonial times, but it first became available as a source of electricity in the early 20th century, when modestly scaled wind chargers supplied power to thousands of American homesteads and farm operations. Soon, however, a built-out grid brought centrally generated electricity to the nation’s rural areas, leaving little room for small-scale wind. It wasn’t until the mid-1970s that the Arab oil embargo and a growing interest in renewable energy gave rise to a second wave of American wind power.

In 1978, the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act (PURPA) broke open the U.S. power market by requiring utilities to buy electricity from independent companies so long as they could generate electricity at less than the “avoided cost” of new utility-generated power. That law paved the way for America’s first commercial wind farm developers. A federal investment tax credit gave wind farms an additional push, particularly in California where a matching state tax credit earned renewable energy investors a 50% combined tax break.

These incentives created a super-heated climate for eager wind energy entrepreneurs. Often relying on minimally tested technology, California’s early wind farms experienced a high rate of mechanical and structural failure, supplying ample fodder to politicians who much preferred mining domestic coal and drilling for oil and gas.

The federal investment tax credit lapsed in 1985 and the California tax credit ratcheted down over the subsequent two years, slowing commitments to new wind projects. A federal incentive for wind was revived in 1992, but this time it was reformulated as a production tax credit that rewarded the actual generation of electricity. Hampered by repeated delays in reauthorization, the federal production tax credit has nevertheless been a key catalyst to wind power’s ascent, reinforced by widely adopted state-level renewable electricity standards that require utilities to increase their reliance on wind and other sources of renewable energy.

The scaling up and declining cost of wind power

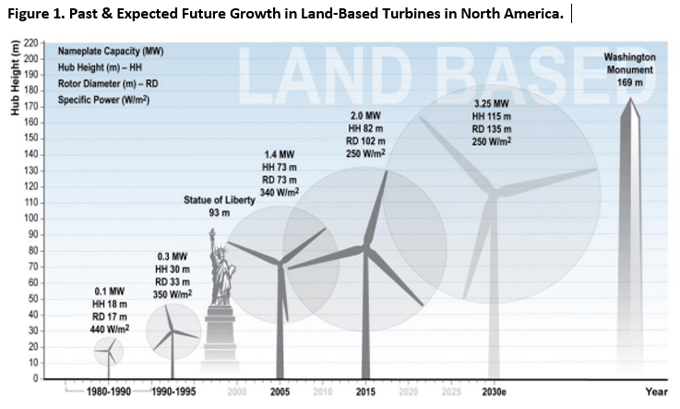

The average wind turbine today is nearly three times taller than turbines built in the early 1990s. [See Figure 1.] This allows modern wind farms to tap the stronger, more constant winds that prevail at higher altitudes. Because wind power increases as the cube of wind speed, the gains from taller towers are particularly momentous.

A further boost to output comes from development and use of much larger rotors. Applying the formula for the area of a circle (A= ??r2), an increase in blade length (i.e. rotor radius) translates into a disproportionate expansion of the rotor’s “swept area,” a key to determining the amount of wind that is captured and converted into electricity.

While wind turbines have grown dramatically in size, the cost of building and operating U.S. wind farms has dropped in recent years, making them now fully competitive with the two other leading sources of new power generation: solar photovoltaics and combined cycle gas. According to Lazard, the levelized cost of land-based wind power ranges from $29 to $56 per megawatt-hour; photovoltaics cost from $36 to $46 per megawatt-hour; and combined cycle gas runs from $41 to $74 per megawatt-hour. Nuclear power is much more expensive at $112 to $189 per megawatt-hour.

The geopolitics of wind

As a non-carbon-emitting technology, wind power has a big environmental advantage over its leading fossil fuel competitors. Onshore and offshore wind has a life cycle carbon footprint of 20 grams or less of CO2 equivalent per kilowatt-hour. The “cleanest” natural gas power plants – those that use combined cycle technology – produce more than 400 grams of CO2 equivalent per kilowatt-hour. Supercritical coal plants – the least polluting in the industry – generate close to 800 grams of CO2 equivalent per kilowatt-hour.

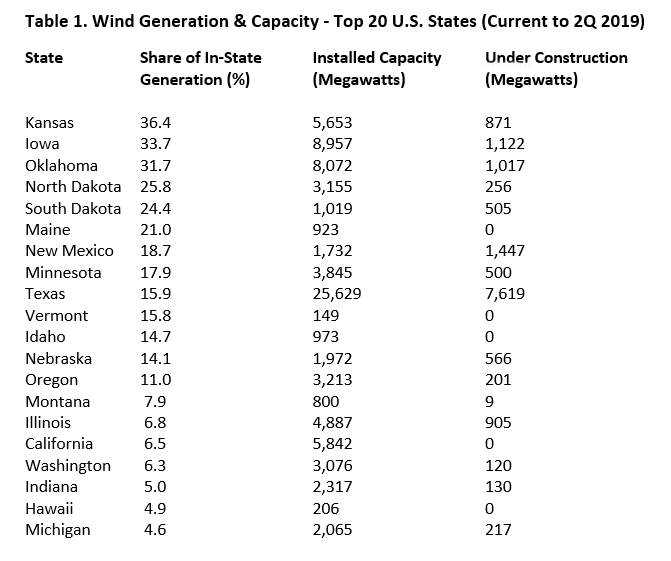

While attractive to many who see climate change as a real and immediate threat, wind power has developed much of its momentum in relatively conservative rural states [see Table 1]. In 2018, 13 states in the nation’s interior region accounted for more than 80% of new wind capacity additions.

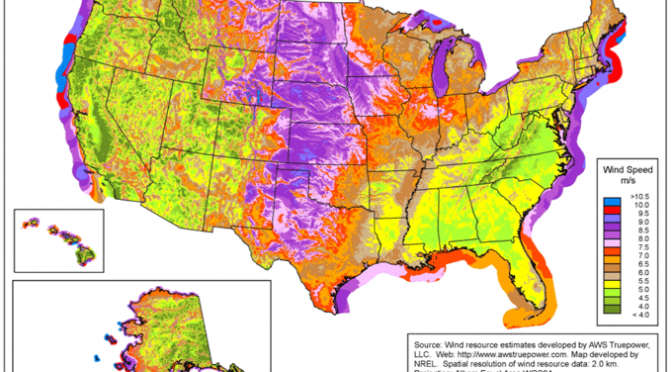

Robust and relatively steady winds in the so-called Wind Belt, from Texas on up through the Dakotas, partially account for the heartland’s heavy investment in wind [see map]. Economics are also at play. Not only are many of the 111,000 American wind power jobs located in rural areas, but substantial financial benefits accrue to farmers and ranchers who lease out small sections of their lands to wind developers. Wind farm-generated tax revenues have also aided many cash-strapped rural communities.

Watching out for birds and bats

Estimates vary, but hundreds of thousands of birds per year are thought to be killed by wind turbines, and those numbers are expected to rise as wind power’s use expands.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has an Avian Radar Project that helps wind developers identify and steer clear of major bird migratory corridors when siting new wind farms. At some operating wind farms where raptors and other vulnerable bird species may be present, specialized detection equipment and human monitors can halt turbines as birds approach.

While bird fatalities are certainly cause for concern, wind energy proponents urge that they be viewed in perspective. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates that 365 to 988 million birds die each year by crashing into building windows, and 89 to 340 million die in collisions with cars. Communication towers and electric utility lines cause millions of additional bird deaths annually. And the ravages of climate change caused by fossil fuel burning will wipe out vastly greater numbers of birds as entire ecosystems are disrupted.

Efforts are also being made to minimize harm to bats living near wind farms. Because bats generally fly in low winds hunting for insects, studies have shown that their mortality rates can be minimized by curtailing wind operations during these times – precisely when there are limited economic gains from keeping turbines running. The Beech Ridge Wind Energy Project, located in a wooded area of West Virginia, has been particularly engaged in these curtailment efforts.

Wind noise

Another commonly expressed concern involves noise resulting from wind power, with neighbors’ complaints ranging from irritability, headaches, and insomnia caused by audible sound to more tenuous claims of inner ear and sense of balance disturbances attributed to ultra-low frequency infrasound. While the transmission of turbine-generated sound can vary with topography and weather conditions, setting a minimum setback for wind turbines from the nearest inhabited buildings and outdoor public spaces is one important step that state and local governing bodies can take to protect wind farm neighbors and reduce public resistance to proposed projects.

Offshore wind – the next frontier

Though well advanced in several European nations, U.S. offshore wind got off to an unfortunate start with New England’s hotly contested Cape Wind project. Proposed for shallow waters near upscale vacation communities on Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard, and Nantucket, Cape Wind met with vigorous opposition. Substantially funded by fossil fuel interests, opponents objected to the project’s high cost to ratepayers, but the anticipated visual impact of turbines on Nantucket Sound drew particular hostility. Backers abandoned Cape Wind in 2018.

There’s new and increasing hope for U.S. offshore wind, with numerous federal leases opening up large expanses of ocean acreage from New England down through the mid-Atlantic. Technology advances, including floating turbines, make it possible to place wind farms in deeper waters, farther from populated coastal areas. Equally important, much lower project costs now make offshore wind a realistic competitor with other sources of power generation. Public concern and official analyses now focus on balancing wind development with fisheries and marine mammal protection and with navigational safety.

The way forward

As U.S. reliance on wind power grows, there is an increased need to build enough energy storage and demand response capability to absorb surplus power when it’s generated and adjust to shortfalls when they occur. Modernized and expanded transmission also will be required, to manage the flow of electricity from diverse energy resources across broad geographical areas. Prioritizing these investments will be essential if wind is to meet its potential as a bulwark against runaway U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.

AUTHOR

Philip Warburg, an environmental lawyer and former president of the Conservation Law Foundation, is the author of Harvest the Wind: America’s Journey to Jobs, Energy Independence, and Climate Stability.