Mohamed Shaker, the minister of electricity and renewable energy, announced in mid-October that the country is to inaugurate the 1.4-GW Benban Solar Park by November.

Located in the Aswan Governorate in Upper Egypt, the solar park has attracted some $2bn in investment, with around 30 companies already establishing energy projects and commercial operations at the site.

Those which have set up operations include international firms such as the Norwegian-headquartered Scatec Solar, Germany’s ib vogt and French company Voltalia.

An important aspect of Benban’s success has been the government’s commitment to purchase electricity produced at the site for the next 25 years, which has helped to incentivize foreign companies.

On top of attracting international investment, the project has involved more than 100 Egyptian companies, creating 640 permanent jobs and 18,000 temporary ones.

The announcement of the official opening at Benban comes at a time when other renewable projects are being expanded.

On October 14 construction officially began on the 250-MW West Bakr wind farm, located 30 km north-west of the town of Ras Ghareb on the east coast.

A total of 96 wind turbines will be constructed at the site, which will produce enough electricity to power 350,000 homes once fully operational in 2021.

The project is being undertaken by Africa-focused renewable energy company Lekela under the government’s build-own-operate scheme and is expected to increase Egypt’s wind energy capacity by 18 percent.

The expansion of solar and wind power forms part of the government’s plans to diversify the energy mix by rapidly expanding the country’s renewable energy capacity.

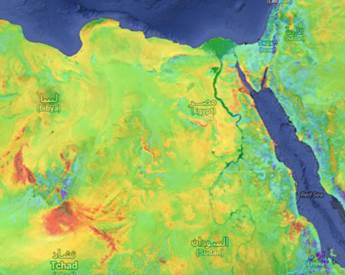

Making up 2 percent of installed generation capacity in 2017, Egypt has set targets to increase this to 20 percent by 2022 and to 42 percent by 2035. Daily sunshine levels range between 9 and 11 hours per day, while median wind speeds reach 8-10 meters per second on the Red Sea coast, and 6-8 meters per second on both the south-west banks of the Nile and southern part of the Western Desert.

Solar and wind are expected to take the place of hydro as the drivers of the country’s renewables mix.

Hydro is the country’s most mature form of renewable energy and made up around half of national power in the 1960s and 1970s. While it is still the largest form of renewable energy in the power mix, with an installed capacity of 2800 MW, it is expected to be eclipsed by solar and wind by FY 2021/22.

In broader terms, the investment in renewables mirrors developments globally, with emerging markets accounting for 63 percent of worldwide investment in renewables in 2017, according to figures from the Frankfurt School of Finance & Management.

Expansion to boost bottom line

In addition to building additional capacity, this expansion will assist Egypt in its efforts to improve its fiscal situation and become a real energy hub.

First, an increase in the amount of renewable energy connected to the grid will cut consumption of oil and gas, which will, in turn, reduce the amount spent on subsidies. The government has recently slashed energy subsidies as part of a series of fiscal reforms, reducing public spending on subsidies from a high of 5.9 percent of GDP in FY 2013/14 to 2.4 percent in FY 2017/18. This shift towards renewables will help achieve its goal of eliminating subsidies completely by 2022.

Furthermore, meeting domestic power needs through renewable resources will free up oil and gas supplies to be used either for export or in other value-added industries.

“While Egypt continues to be a net importer of oil, it has become self-sufficient in the production of natural gas. By shifting the burden of power production to renewables, extracted resources can be diverted to industries where they will have a more significant economic impact,” Mohamed Amer, country director of Scatec Solar Egypt, told OBG.

“The economic argument for this is strengthened, as the cost of producing renewable energy has fallen below the cost of energy from traditional sources.”

Last year, the country was given an example of how shifts in energy availability can impact state finances. After achieving gas self-sufficiency by increasing production at the Zohr offshore field, the government announced that it had halted liquefied natural gas imports – a decision expected to save the country $3bn annually.

By Oxford Business Group