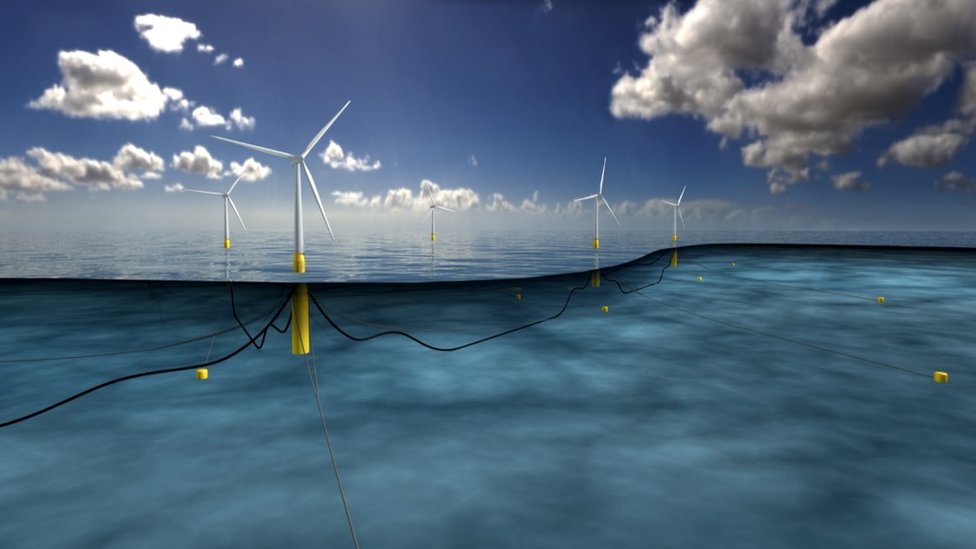

Wind turbines floating miles out to sea could one day provide electricity to our homes, experts believe.

Wales currently meets about 50% of its needs from renewable sources, including solar and wind.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson wants to see fixed offshore wind farms power UK homes by 2030, while Plaid Cymru believes Wales could be self-sustainable through renewables by then.

But how big a part could turbines floating off the Welsh coast play?

A 96 megawatt (MW) wind farm capable of powering 90,000 homes is proposed for an area of sea 28 miles (45km) off Pembrokeshire by 2027.

However, this could be just the tip of the iceberg, in light of other developments.

Successful trials in Scotland suggest floating turbines could have advantages over other types of renewables, including cost and environmental impact.

Tidal lagoons, for example, have proved hard to get off the ground because of the large upfront investment needed to build, with no return for a number of years, according to Cardiff University professor of renewable energy Nick Jenkins.

A proposed £1.3bn Swansea Bay project was shelved because of cost.

Placing solar panels and wind turbines on a large scale in rural Wales can also be difficult, with objections from campaigners and locals over the impact on the landscape.

As Wales has about 1,680 miles (2,704 km) of coast, generating electricity there could be the obvious solution.

“The fact that these (floating) turbines are so far out to sea make them less visible,” said Rhodri James, of global energy firm Equinor.

“It does help, as some people in certain areas don’t want to see them. And in protected areas, such as Pembrokeshire National Park, putting them close to the shore might be difficult.”

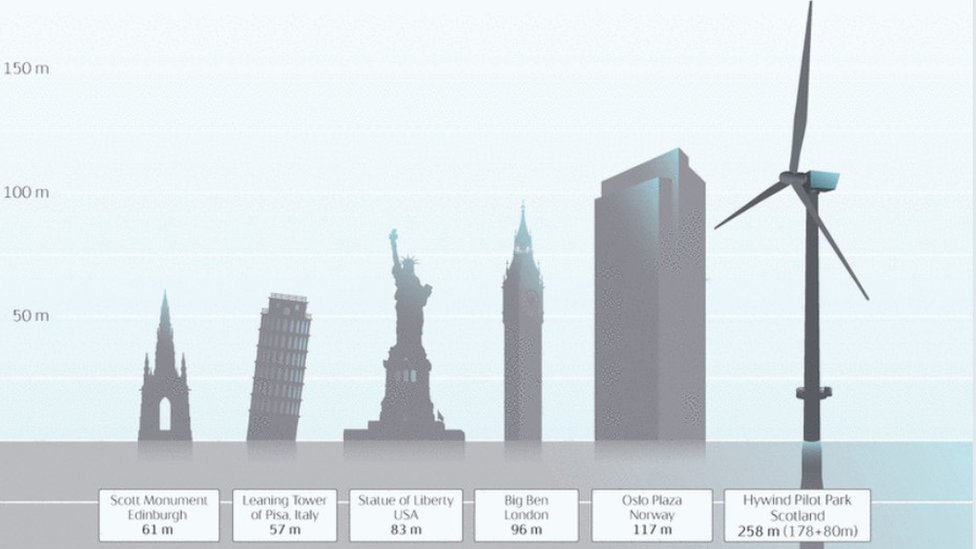

There are also other benefits, such as saving on the expense on steel to fix turbines 60m underwater into the seabed, and the higher wind speeds further out to sea and potentially more power generated.

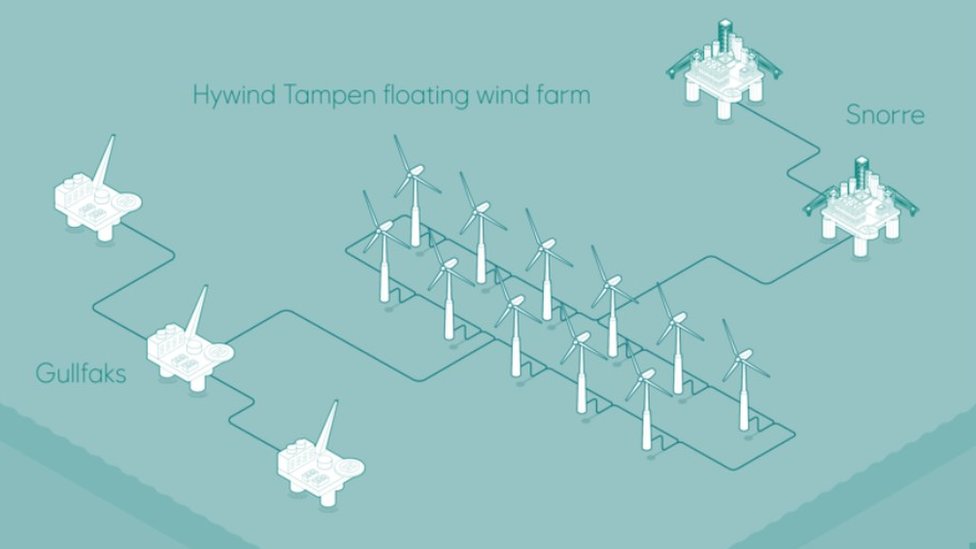

Global energy company Equinor first had the idea of floating turbines in 2001, to power offshore oil and gas platforms in Norwegian waters.

These were run off diesel, which proved expensive and bad for the environment.

While the initial aim was to provide clean energy at low cost, Mr James said Equinor quickly realised this was scratching the surface, adding: “It had the potential to feed into the National Grid if done on a utility scale.”

Mr James said adding more turbines reduced costs because of more power generated and saw expenditure per megawatt reduced by 70% with hopes of a further 40% cut.

Fixed platforms are generally placed up to a depth of 60m, with floating turbines able to go in waters up to 1,000m.

“Pembrokeshire is the most favourable part of Wales as it has deep waters. There is a fair bit of offshore generation off north Wales, but they are fixed platforms in shallower waters,” Mr James added.

“Wales is well-placed as an area to look into further as is Cornwall, Ireland, the Celtic Sea, but it’s currently more extensive in Scotland, where there will be more tests and demonstrations and we are very confident of moving to full scale.”

Currently, UK offshore farms produce about 10 gigawatts (GW) of power, with a target of 40GW by 2030.

A recent Welsh Government report said just two or three farms could provide 2GW of power, enough for more than a million homes.

Graham Ayling, of the Energy Saving Trust, said the potential to create infrastructure “looks promising” and Wales could be self-sufficient from green energy within a decade.

“Given the pace that renewable technologies have been deployed and developed, and the cost reductions that have been seen in recent years, it is possible that Wales may well meet 100% of its electricity needs from renewable sources by 2030,” he said.

Being self-sustainable in renewables by the end of the 2020s was something proposed by Plaid Cymru in its 2019 General Election manifesto.

Environment spokesman Llyr Gruffydd said wave and tidal sources off Pembrokeshire, in the Celtic Sea and off Anglesey were “some of the best potential renewable energy resource in the world”.

He said utilising these should be “a strategic priority”, but also the most promising forms of renewable energy are emerging technologies and will not be fully utilised until the end of the decade.

Meanwhile, Mr Gruffydd wants to see investment in research, development and building skills in the workforce, so the country is ready to take advantage in areas such as floating wind technology.

The Welsh Conservatives’ energy spokeswoman Janet Finch-Saunders said Wales’ natural resources provide the opportunity to help stimulate the economy with the creation of “long-term green-collar jobs”.

By Chris Wood

BBC News