Last year was a record breaker for the UK’s wind power industry.

Wind generation reached its highest ever level, at 17.2GW on 18 December, while wind power achieved its biggest share of UK energy production, at 60% on 26 August.

Yet occasionally the huge offshore wind farms pump out far more electricity than the country needs – such as during the first Covid-19 lockdown last spring when demand for electricity sagged.

But what if you could use that excess power for something else?

“What we’re aiming to do is generate hydrogen directly from offshore wind,” says Stephen Matthews, Hydrogen Lead at sustainability consultancy ERM.

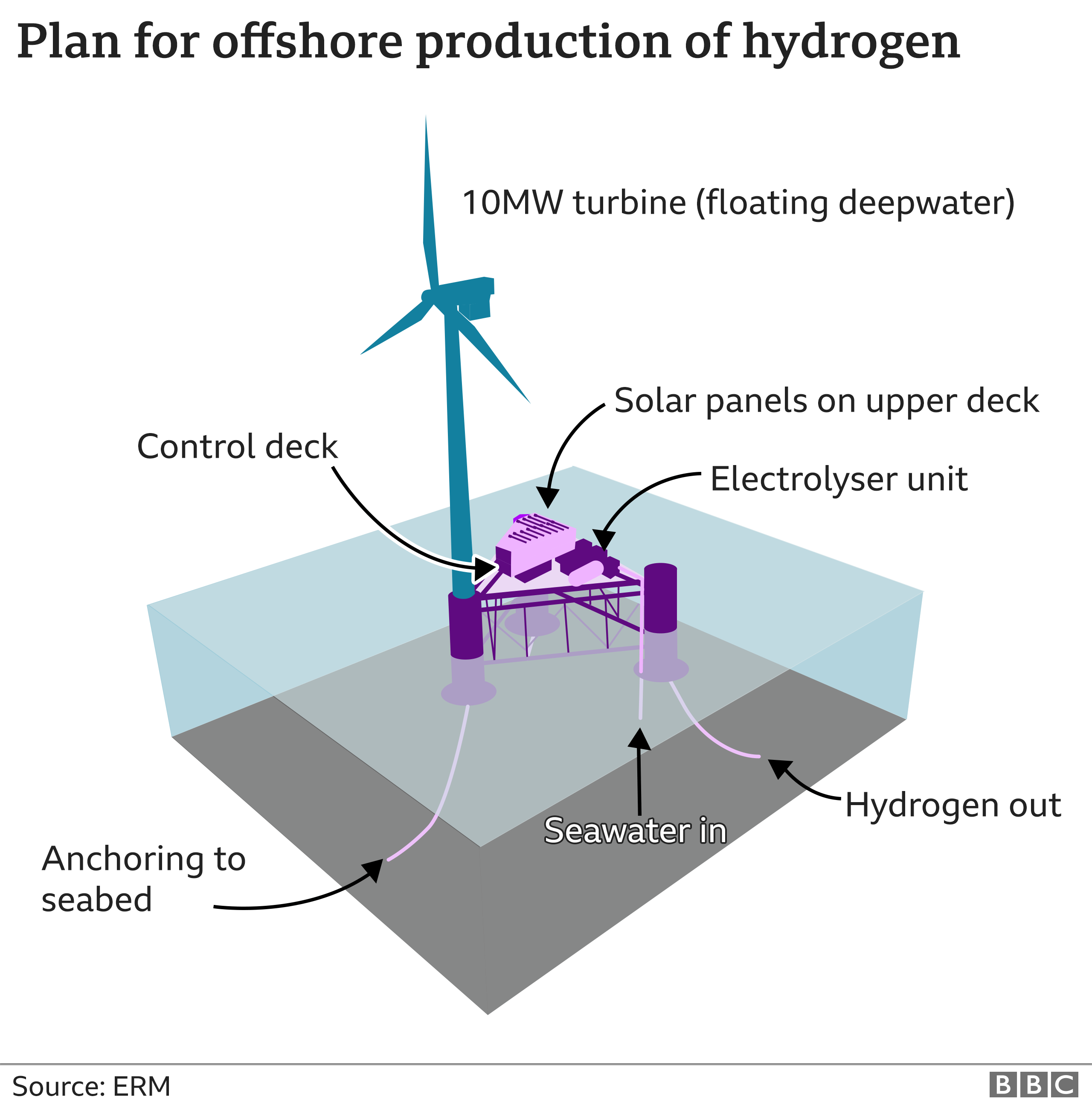

His firm’s project, Dolphyn, aims to fit floating wind turbines with desalination equipment to remove salt from seawater, and electrolysers to split the resulting freshwater into oxygen and the sought-after hydrogen.

The idea of using excess wind energy to make hydrogen has sparked great interest, not least because governments are looking to move towards greener energy systems within the next 30 years, under the terms of the Paris climate agreement.

Hydrogen is predicted to be an important component in these systems and may be used in vehicles or in power plants. But for that to happen, production of the gas, which produces zero greenhouse gas emissions when burned, will need to dramatically increase in the coming decades.

Mr Matthews says his firm’s project is just getting going, with a prototype system using a floating wind turbine of roughly 10 megawatt capacity planned, but not yet built.

It’s possible that the system could be based in Scotland and the aim is to start producing hydrogen around 2024 or 2025.

But there are many other ventures in this area besides Dolphyn.

Wind turbine maker Siemens Gamesa and energy firm Siemens Energy are ploughing 120m euros ($145m; £105m) into the development of an offshore turbine with a built-in electrolyser.

German energy company Tractebel is exploring the possibility of building a large-scale, offshore hydrogen production plant powered by nearby wind turbines; and UK-headquartered Neptune Energy is seeking to convert an oil platform into a hydrogen production station, which will pump hydrogen ashore to the Netherlands via pipes that are currently transporting natural gas.

All of the excitement around hybrid wind energy and hydrogen generation systems is partly down to climate commitments but economics are also involved.

Large-scale hydrogen electrolysers are becoming more available while the costs of installing wind turbines has fallen “dramatically”, says James Carton, assistant professor in sustainable energy at Dublin City University.

He and others think the time is right to kick-start large-scale hydrogen electrolysis at sea, though the idea has been around for many years.

Oyster is yet another project in this area, and involves a consortium of companies including Danish energy firm Ørsted and British electrolyser specialists ITM Power, among others.

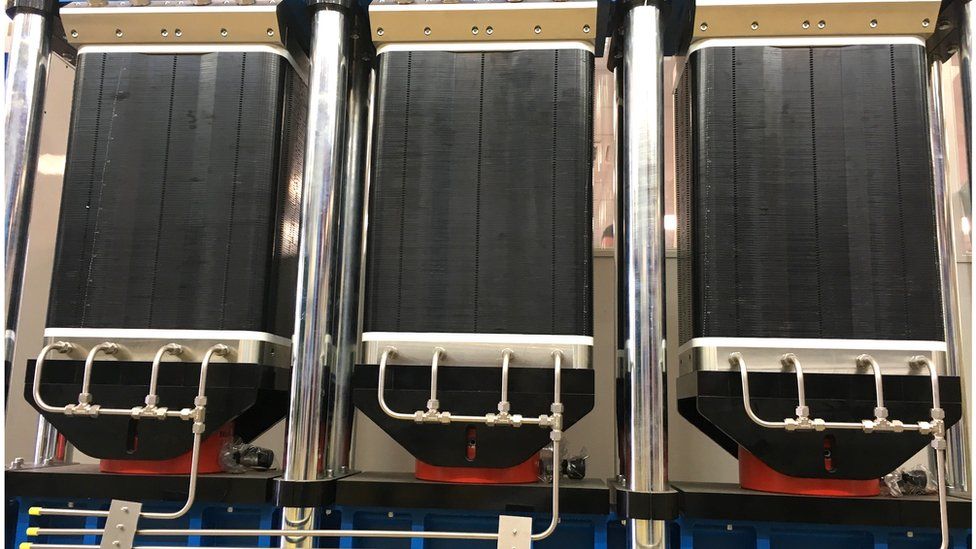

In the first instance, a wind turbine will power an onshore electrolyser that will churn out hydrogen. The device will be exposed to sea spray to simulate, to a degree, the harsh environment facing offshore equipment. ITM intends to design a system compact enough to fit into a single wind turbine.

The firm’s chief executive, Graham Cooley, points out that it is much easier to store molecules such as hydrogen than electrons in batteries.

“All the renewable energy companies… they’ve realised they’ve got a new product,” he adds. “Now they can supply renewable molecules to the gas grid and industry.”

The Oyster consortium hopes to have shown off a demonstrator of its system within 18 months.

Among the many potential uses for hydrogen is as a fuel for gas-burning boilers in homes. Converting the domestic gas grid to provide hydrogen, and fitting homes with boilers capable of burning it, would be a huge task.

However, it would mean that excess wind energy could in principle be used to supply this giant system, meaning very little of that energy would go to waste, says Mr Carton, referring to the gas main pipes scattered around the UK and Ireland: “We have a big tank, it’s just a really long tank in the ground.”

For some, this is all very exciting. But there are hurdles yet to overcome. A spokesman for the wind energy industry body WindEurope says that while renewable hydrogen produced via wind-powered electrolysis is “future-proof”, a decade or so of technological development is required before these systems will have a larger impact.

Jon Gluyas, Ørsted/Ikon chair in geoenergy, carbon capture and storage at Durham University, adds that the real question is whether it is cost-effective to set up such equipment at scale. Proponents, unsurprisingly, argue it is – but with energy systems the proof is only ever in the pudding. Ultimately, Prof Gluyas says a mix of different technologies and approaches will be needed for countries like the UK to be carbon neutral.

For Mr Carton, the vision remains tantalising. Schemes that solve the problem of wind’s variability by using excess power to good use could be transformative, he argues: “It’ll change the way we look at renewables.”

By Chris Baraniuk

Technology of Business reporter, BBC