American offshore wind farms, of which there are 17 in the works for the Atlantic Ocean, are no longer far off on the horizon. The overall magnitude of this emerging renewable energy industry is starting to take shape.

Off the coast of New Jersey these days, surveillance vessels hired by European energy companies are taking measurements of the ocean depths, and underwater research drones are analyzing water temperatures to accumulate data on the Mid-Atlantic “Cold Pool.”

Onshore in places like the Port of Paulsboro along the Delaware River south of Camden and Philadelphia, labor unions, port officials and politicians are angling for new marine terminals to build and ship off massive steel monopiles.

And in weekly board meetings, state-appointed officials in charge of the Garden State’s public utilities are discussing massive overhauls to the power grid and many miles of new transmission lines.

Billions of dollars will be invested in the next several years — at sea and on land — to erect hundreds of wind turbines miles from the coast in order to bring New Jersey 7,500 megawatts of renewable energy. That’s enough to power half of the state’s 1.5 million homes.

Eight other states along the Eastern Seaboard of the United States have embarked on similar endeavors, preparing for the arrival of a new era in American energy.

“Wind energy is going to be real. It’s just a question of how much,” EnvironmentNJ executive director Doug O’Malley said. “Flooding down the shore is real. Our number one priority is how our coastal communities are going to be a generation from now. Who knows if we’re here in 2050? We need to study this as much as possible, but also understand we need to look at the full picture of climate change.”

Offshore Wind Farms: The Lease Areas and Developers

Seventeen federally leased areas are off the coasts of eight U.S. states. Click on each lease site to see how many turbines are expected or estimated, to which developer they belong and how much power will be generated. Turbine totals are either based on developers’ proposals or estimated using power generated by the largest turbine currently on the market.

Dire predictions of climate change and how to most quickly pivot to clean energy have fueled the embrace of offshore wind. And while most stakeholders seem on board with the nearly Eiffel Tower-sized turbines, the fishing industry remains a holdout. Meanwhile, the cumulative effect of so many turbines spread across the Mid-Atlantic Bight remains unknown. The bight stretches from the Outer Banks of North Carolina to the Gulf of Maine.

Only seven wind turbines currently rotate in American waters, but more than 1,500 are in planning or development stages from North Carolina to Massachusetts, according to an NBC10 Philadelphia analysis of the federally leased areas and the 19 projects currently in development. The analysis used data from federal and state agencies as well as individual project proposals. Some proposals have cited specifically how many turbines will be built. For others, an estimate was made using the megawatts approved for a project divided by the energy generated by the most powerful turbines on the market. Currently, General Electric is able to construct a 12-megawatt giant called the Haliede X that can power a single-family home for two days with just a single rotation of its blades.

The turbines will occupy areas of the continental shelf encompassing 2,722 square miles — larger than the state of Delaware — and most energy experts believe the ones currently in planning stage are only the first wave.

“We’re talking about a huge amount of offshore resources,” Theodore Paradise, senior vice president of transmission engineering firm Anbaric, said. “We’re talking about massively more than these numbers. (States are) making what feels very big in procurement targets.”

Several developers, all European, have submitted construction proposals to the federal government to build out wind farms by the late 2020s. None have been approved yet, even though the first few have sat in a queue at the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management since 2018.

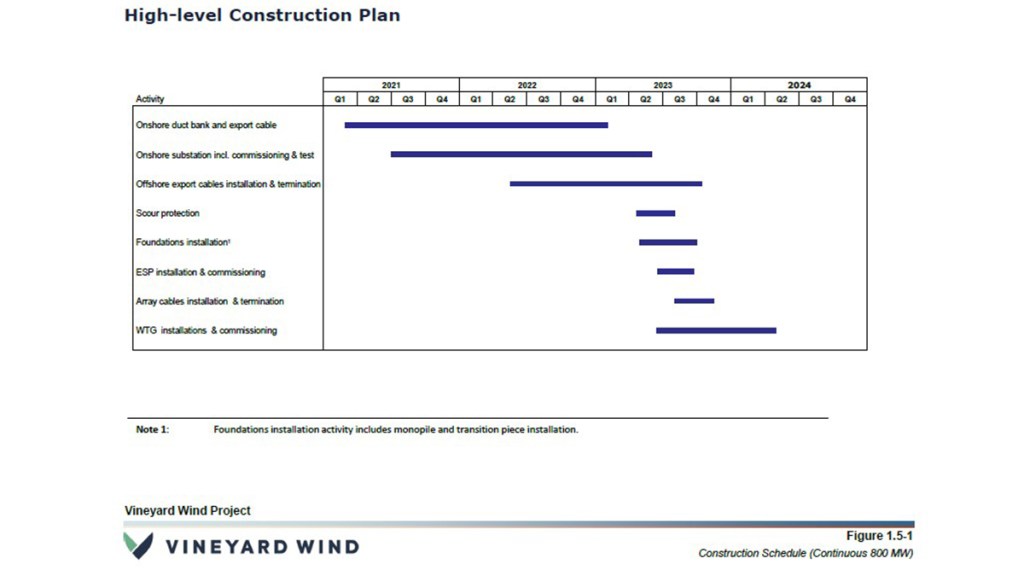

The first farm in the federal queue, Vineyard Wind off Massachusetts, was given its final environmental impact study by BOEM this month, and industry leaders now believe the federal permitting process will pick up under President Joe Biden.

“The United States is poised to become a global clean energy leader,” U.S. Interior Department Assistant Secretary Laura Daniel Davis said in announcing Vineyard Wind’s environmental approval on March 8. “To realize the full environmental and economic benefits of offshore wind, we must work together to ensure all potential development is advanced with robust stakeholder outreach and scientific integrity.”

Vineyard estimates turbines could begin powering Massachusetts homes in mid-2024, according to its most recent timeline presented to BOEM.

Politicians, environmentalists and European companies have invested interest in the plans. Big issues still to confront include lucrative North Atlantic fishing concerns; ecological effects on what is known as the Mid-Atlantic Bight’s “Cold Pool”; and the fundamental remaking of power grids that bring the electricity into homes and businesses of 100 million Americans.

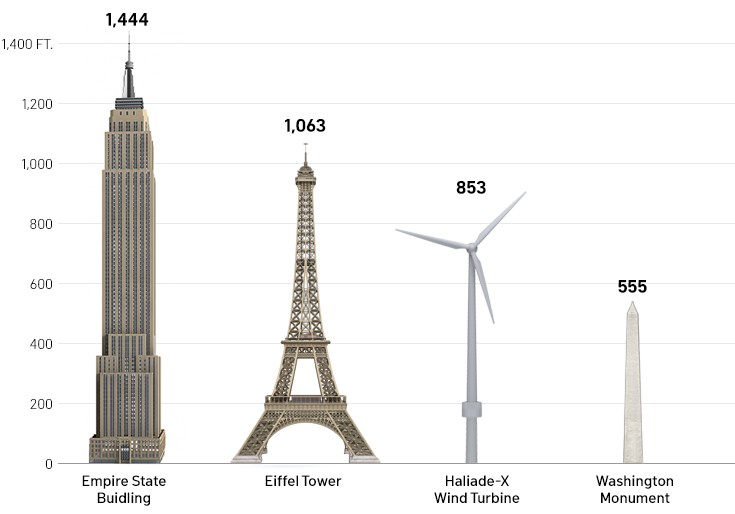

Rising Heights of Offshore Wind Turbines

Wind turbines in the ocean are much bigger than the on-land versions that dominate the landscape in places like the American Midwest. Here is how the largest turbine on the market, General Electric’s 12MW Haliede X, compares in size to some well-known structures.

What is the Mid-Atlantic Bight’s ‘Cold Pool’? How Would 1,000s of Turbines Affect It?

Every year off the coast of the eastern United States, from Cape Hatteras in North Carolina to Cape Cod in Massachusetts, forms a unique oceanographic feature called “the Cold Pool.”

It’s a layering of water temperatures that makes for breathtakingly cold water near the ocean floor and much warmer water near the surface and beaches. The effect is called stratification, and it is created each spring, peaks each summer and mixes up once again each fall.

The stark difference in water temperature during the late spring and summer months makes it one of Earth’s unique marine ecosystems. It gives the continental shelf off the northeastern United States a diversity of fauna that has persisted for centuries. Fishermen and scientists alike credit the Cold Pool with powering the renowned fisheries of New England, New Jersey and Maryland.

No one knows the extent to which thousands of wind turbines would have on the stratification process, or if the twirling horizon-scrapers will affect the Cold Pool at all.

For much of the last decade, offshore wind advocates analyzed the potential — and ecological effects — of the renewable energy at the individual turbine level and at the farm level.

A third way of looking at the new energy source has only recently emerged.

“The third level is, what happens if you have 10 of these wind facilities that are near each other?” said Josh Kohut, a marine biologist at Rutgers University’s Center for Ocean Observing Leadership.

Kohut and his colleagues at RU COOL released a research paper in late January that looked for potential effects on the Cold Pool through the lens of European offshore wind projects.

“The scale of the impact of these wind farms has the potential to alter the unique and delicate oceanographic conditions along the expansive Atlantic continental shelf,'” the report summary reads.

Northern Europe, from Scotland to Germany, has a two-decade head start on the United States in the offshore wind realm. More than 5,000 turbines currently operate off the coasts of eight countries there, pumping 25 gigawatts of energy into power grids.

The Rutgers team studied the continent’s 110 farms, looking for similar ecological areas to compare with the Mid-Atlantic Bight and its Cold Pool.

Two places, in particular, stood out: the Irish Sea off Scotland and the German Bight in the North Sea.

But the report found that differences in the stratification of the European bodies of water make the research conducted off the other continent difficult to directly compare with the Mid-Atlantic Bight.

“The potential for these multiple wind energy arrays to alter oceanographic processes, and the biological systems that rely on them is possible,” the report summary said. “However, a great deal of uncertainty remains about the nature and scale of these interactions.”

The Rutgers team concluded more data and analysis is needed. Kohut said technology makes it possible to get a better sense of the cumulative effect of the Cold Pool in the next couple years.

He said his team continues looking at European wind farms’ effects on ocean stratification there while also deploying an underwater drone off of the New Jersey coast to get data from the Cold Pool.

“Our objective is to get the latest and best science available to the people making these decisions,” Kohut said.

The European study was funded by the Science Center for Marine Fisheries, a group with fishing industry affiliations that seeks to promote sustainable fisheries.

“We didn’t know the scale and depth and rate at which wind mills would develop,” SCEMFIS chairman Greg DiDomenico, of Cape May, N.J.-based Lund Fisheries, said in an interview. “It’s now at a tremendous pace. We have not heard what will be the impact of that type of development on the Mid-Atlantic ecosystem. And if in fact, it’s wind mills at any cost, then someone needs to tell us that.”

O’Malley, the executive director of EnvironmentNJ, which advocates for environmental issues in the Garden State, said more studies on the ecological impact of offshore wind is welcome. But, he added, studies have been going on for years already and “the Cold Pool is going to be affected by climate change like the rest of ocean” if nothing is done to stem the reliance on fossil fuels.

“We’ve been strongly advocating for offshore wind and also for looking at all the site locations and the impacts,” O’Malley said. “The ocean is a big place but also a busy place. The hope is there is a way to accommodate for offshore wind and also the ecology of the ocean.”

A Fundamental Change to the Way Power Is Delivered

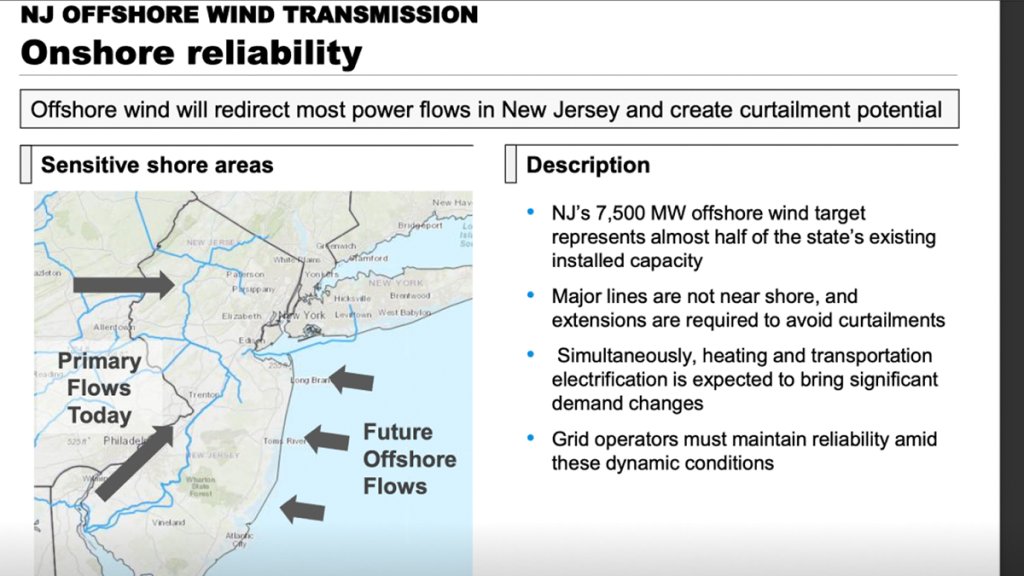

For the last century, the energy grid has connected power plants, fueled by coal, oil and gas, to homes and businesses through a network of utility lines and power substations. In more recent decades, nuclear plants helped wean the country off of a strictly fossil fuel diet. Still, every decade or so, a meltdown — whether it was in Pennsylvania, or Russia, or Japan — as well as the fossil fuel industry hindered a full embrace of nuclear power.

Traditionally, power plants have been closer to the center of the country — places like Ohio, West Virginia, western Pennsylvania, Tennessee where fossil fuels were mined.

At a conference of offshore wind industry leaders and experts in energy infrastructure hosted by the New Jersey Board of Utilities in late February, one utility executive said the power grid is “used to a west-east flow of energy” and “as we move into this new era, we’re going to encounter a very different set of problems.”

Re-routing the flow of energy is not a cheap problem.

In traditional terms, energy experts say adding a mile of transmission line can cost $1 million. Many miles of new offshore transmission lines will be part of the cost to connect to offshore wind farms. But it won’t be the only cost.

Power grid operators like the PJM Interconnection have to upgrade many of the onshore power substations where the new wind farms off the coast will connect to the grid. PJM is a regional transmission operator headquartered in Valley Forge, Pa., that connects power to 65 million Americans in 13 states. It was formed in the late 1920s when New Jersey and Pennsylvania combined their public utility grid, and grew to incorporate other states as far west as Ohio and Tennessee and south to parts of North Carolina. New York state has its own system, as does New England.

The cost to upgrade substations up and down the coast will likely run into the billions, for each state.

Take New Jersey, where two would-be projects, Ørsted’s Ocean Wind and EDF Renewable/Shell New Energies’ Atlantic Shores, have already put in requests to PJM for substation upgrades.

Their requests collectively add up to $3.5 billion, according to an NBC10 Philadelphia review of wind energy entries in the PJM New Service Queue.

And that cost is only for projects that would provide up to 3,000 megawatts from wind farms, less than half the 7,500 megawatts from offshore wind that Gov. Phil Murphy has mandated by 2035.

Officials with New Jersey’s Board of Public Utilities and PJM have told NBC10 Philadelphia that all of those costs will never be realized. They say that prudent planning now in order to integrate the eventual 7,500 megawatts will save consumers in the long run.

The $3.5 billion in current requests, according to BPU and PJM officials, will change or disappear altogether when some of the first upgrades are completed. They also say the total doesn’t reflect the work being done now to avoid “pancaking” upgrades to the transmission grid.

New Jersey became the first state in November 2020 to sign a “state agreement” approach to offshore wind upgrades with PJM. The initiative is designed to account for future offshore wind projects that are not yet proposed.

“We are blazing the trail as we walk,” BPU manager of regulatory affairs Joseph DeLosa said. “We’re the first do the state agreement approach with PJM.”

Additionally, developers will pick up part of the tab for transmission upgrades and spread that cost across many years, officials with BPU and the state’s public utilities say.

“Everything we’re doing, all of our clean energy objectives, taking the state to 100% clean energy depends on the transmission system being able to take the power to customer,” BPU’s general counsel, Abraham Silverman, said. “If you don’t have that, we’re just really behind.”

Infrastructure experts believe the upgrades in the end are integrating a renewable energy with more reliable market prices than fossil fuels.

“Is this going to be $3 or $4 billion? That seems like a lot of money, but it’s (spread) over decades,” Paradise, the senior vice president at Anbaric, said. “The exciting thing for customers is the power you get from that is a free source.”

He noted that the biggest cost in any energy user’s bill now is the price of the commodity itself, be it oil or gas. That won’t be the case with offshore wind.

“Wind is free. You don’t have to fill up the tank everyday,” Paradise said.

nbcphiladelphia.com