Solar thermal power/electric generation systems collect and concentrate sunlight to produce the high temperature heat needed to generate electricity. All solar thermal power systems have solar energy collectors with two main components: reflectors (mirrors) that capture and focus sunlight onto a receiver. In most types of systems, a heat-transfer fluid is heated and circulated in the receiver and used to produce steam. The steam is converted into mechanical energy in a turbine, which powers a generator to produce electricity. Solar thermal power systems have tracking systems that keep sunlight focused onto the receiver throughout the day as the sun changes position in the sky. Solar thermal power plants usually have a large field or array of collectors that supply heat to a turbine and generator. Several solar thermal power facilities in the United States have two or more solar power plants with separate arrays and generators.

Parabolic trough power plant

Source: Stock photography (copyrighted)

Solar thermal power systems may also have a thermal energy storage system component that allows the solar collector system to heat an energy storage system during the day, and the heat from the storage system is used to produce electricity in the evening or during cloudy weather. Solar thermal power plants may also be hybrid systems that use other fuels (usually natural gas) to supplement energy from the sun during periods of low solar radiation.

Types of concentrating solar thermal power plants

There are three main types of concentrating solar thermal power systems:

- Linear concentrating systems, which include parabolic troughs and linear Fresnel reflectors

- Solar power towers

- Solar dish/engine systems

Linear concentrating systems

Linear concentrating systems collect the sun’s energy using long, rectangular, curved (U-shaped) mirrors. The mirrors focus sunlight onto receivers (tubes) that run the length of the mirrors. The concentrated sunlight heats a fluid flowing through the tubes. The fluid is sent to a heat exchanger to boil water in a conventional steam-turbine generator to produce electricity. There are two major types of linear concentrator systems: parabolic trough systems, where receiver tubes are positioned along the focal line of each parabolic mirror, and linear Fresnel reflector systems, where one receiver tube is positioned above several mirrors to allow the mirrors greater mobility in tracking the sun.

A linear concentrating collector power plant has a large number, or field, of collectors in parallel rows that are typically aligned in a north-south orientation to maximize solar energy collection. This configuration enables the mirrors to track the sun from east to west during the day and concentrate sunlight continuously onto the receiver tubes.

Parabolic troughs

A parabolic trough collector has a long parabolic-shaped reflector that focuses the sun’s rays on a receiver pipe located at the focus of the parabola. The collector tilts with the sun to keep sunlight focused on the receiver as the sun moves from east to west during the day.

Because of its parabolic shape, a trough can focus the sunlight from 30 times to 100 times its normal intensity (concentration ratio) on the receiver pipe, located along the focal line of the trough, achieving operating temperatures higher than 750°F.

Parabolic trough linear concentrating systems are used in one of the longest operating solar thermal power facilities in the world, the Solar Energy Generating System (SEGS) located in the Mojave Desert in California. The facility has had nine separate plants over time, with the first plant in the system, SEGS I, operating from 1984 to 2015, and the second, SEGS II, operating from 1985 to 2015. SEGS III–VII (3–7), each with net summer electric generation capacities of 36 megawatts (MW), came online in 1986, 1987, and 1988. SEGS VIII (8) and IX (9), each with a net summer electric generation capacity of 88 MW, began operation in 1989 and 1990, respectively. SEGS 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 all ceased operation in 2021, leaving only SEGS 9 in operation as of December 31, 2021.

In addition to the SEGS 9, the other parabolic-trough solar thermal electric facilities operating in the United States as of December 2021, and their net summer electric generation capacity, location, and year of initial operation are:

- Solana Generating Station: a 296 MW, two-plant facility with an energy storage component in Gila Bend, Arizona, that started operating in 2013

- Mojave Solar Project: a 2275 MW, two-plant facility in Barstow, California, that started operating in 2014

- Genesis Solar Energy Project: a 250 MW, two-plant facility in Blythe, California, that started operating in 2013 and 2014

- Nevada Solar One: a 69 MW plant near Boulder City, Nevada, that started operating in 2007

Linear Fresnel reflectors

Linear Fresnel reflector (LFR) systems are similar to parabolic trough systems in that mirrors (reflectors) concentrate sunlight onto a receiver located above the mirrors. These reflectors use the Fresnel lens effect, which allows for a concentrating mirror with a large aperture and short focal length. These systems are capable of concentrating the sun’s energy to approximately 30 times its normal intensity. Compact linear Fresnel reflectors (CLFR)—also referred to as concentrating linear Fresnel reflectors—are a type of LFR technology that has multiple absorbers within the vicinity of the mirrors. Multiple receivers allow the mirrors to change their inclination to minimize how much they block adjacent reflectors’ access to sunlight. This positioning improves system efficiency and reduces material requirements and costs. A demonstration CLFR solar power plant was built near Bakersfield, California, in 2008, but it is currently not operational.

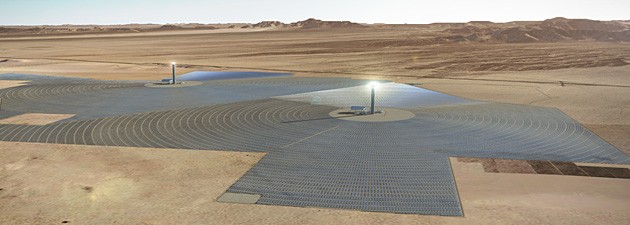

Solar power towers

A solar power tower system uses a large field of flat, sun-tracking mirrors called heliostats to reflect and concentrate sunlight onto a receiver on the top of a tower. Sunlight can be concentrated as much as 1,500 times. Some power towers use water as the heat-transfer fluid. Advanced designs are experimenting with molten nitrate salt because of its superior heat transfer and energy storage capabilities. The thermal energy-storage capability allows the system to produce electricity during cloudy weather or at night.

The U.S. Department of Energy, along with several electric utilities, built and operated the first demonstration solar power tower near Barstow, California, during the 1980s and 1990s. In 2021, there were two solar power tower facilities operating in the United States:

- Ivanpah Solar Power Facility: a facility with three separate collector fields and towers with a combined net summer electric generation capacity of 393 MW in Ivanpah Dry Lake, California, that started operating in 2013

- Crescent Dunes Solar Energy Project: a 110 MW one-tower facility with an energy storage component in Tonapah, Nevada, that started operating in 2015

Solar power tower

Source: National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL)

Solar dish/engines

Source: Stock photography (copyrighted)

Solar dish/engines

Solar dish/engine systems use a mirrored dish similar to a very large satellite dish. To reduce costs, the mirrored dish is usually composed of many smaller flat mirrors formed into a dish shape. The dish-shaped surface directs and concentrates sunlight onto a thermal receiver, which absorbs and collects the heat and transfers it to an engine generator. The most common type of heat engine used in dish/engine systems is the Stirling engine. This system uses the fluid heated by the receiver to move pistons and create mechanical power. The mechanical power runs a generator or alternator to produce electricity.

Solar dish/engine systems always point straight at the sun and concentrate the solar energy at the focal point of the dish. A solar dish’s concentration ratio is much higher than linear concentrating systems, and it has a working fluid temperature higher than 1,380°F. The power-generating equipment used with a solar dish can be mounted at the focal point of the dish, making it well suited for remote locations, or the energy may be collected from a number of installations and converted into electricity at a central point.

There are no utility-scale solar dish/engine projects in commercial operation in the United States.