Investment required by 2026 if sector is to meet forecasted 5-fold growth in annual installations by 2030, with greater sum of US$100 billion needed to hit global government targets by the end of the decade.

The global offshore wind supply chain will require US$ 27 billion of secured investment by 2026 if it is to meet a fivefold growth in annual installations (excluding China) by 2030, according to latest Horizons report by Wood Mackenzie, a global insight business for renewables, energy and natural resources.

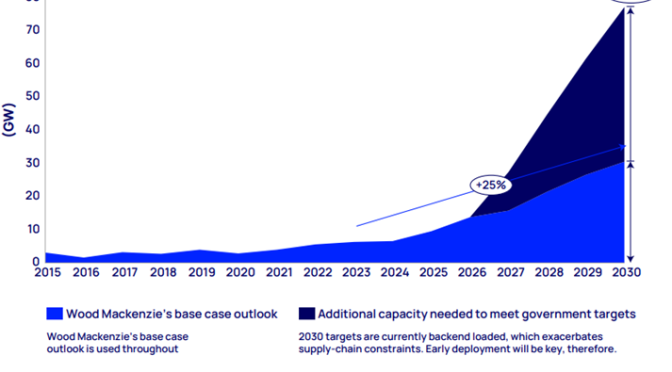

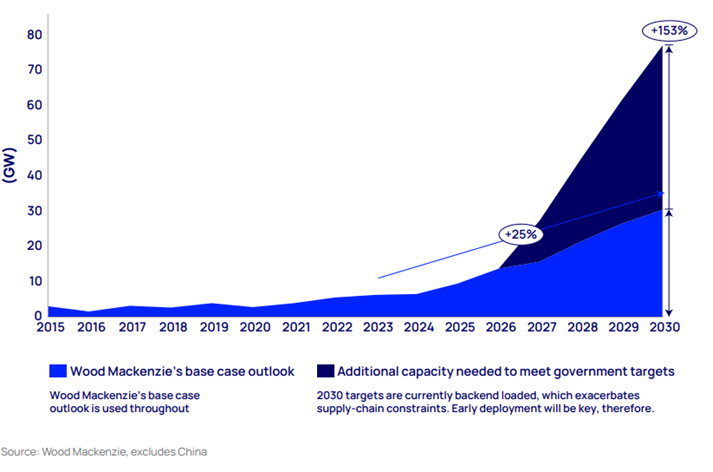

This figure is based on Wood Mackenzie’s base case outlook which forecasts annual capacity additions to hit 30 gigawatts (GW) by 2030, but is dwarfed by policymakers’ offshore wind targets, which would require nearly 80 GW per year. To hit this goal set by governments across the world, the supply chain is estimated to require more than US$100 billion in investment.

These findings come from: ‘Cross currents: Charting a sustainable course for offshore wind’, Wood Mackenzie’s analysis into current offshore wind supply chain constraints, investment barriers and what’s required to scale up.

Difference between Wood Mackenzie’s offshore wind outlook and 2030 government targets:

“Governments have made clear their commitment to offshore wind as an important pillar of decarbonisation and energy security. However, the supply chain is struggling to scale up and will be an impediment to achieving decarbonisation targets if change does not happen,” said Chris Seiple, Vice Chair, Power and Renewables at Wood Mackenzie, co-author of the report.

Seiple added: “Nearly 80 GW of annual installations to meet all government targets is not realistic, even achieving our forecasted 30 GW in additions will prove unrealistic if there isn’t immediate investment in the supply chain. Adjustments and new policies by governments and developers will be required to transform the supply chain to deliver offshore wind projects at industrial scale.”

Why is it hard to drum up investment?

- Low offshore margins make the investment case more challenging

“The oversupply that resulted from the 2015 supply chain buildout is one of the factors depressing profitability, which saw the industry boost its capacity to supply around 800 turbines, compared to the yearly average of 500 since then. Suppliers are now also having to cope with the inflation of the past two years and higher commodity input costs,” said Seiple.

Seiple added: “Burned once, current suppliers are cautious in their investment plans and the lack of profitability is hampering their ability to fund manufacturing capacity expansion – ultimately stalling innovation in the sector.”

- Uncertainty of project timing could result in very different supply-chain needs

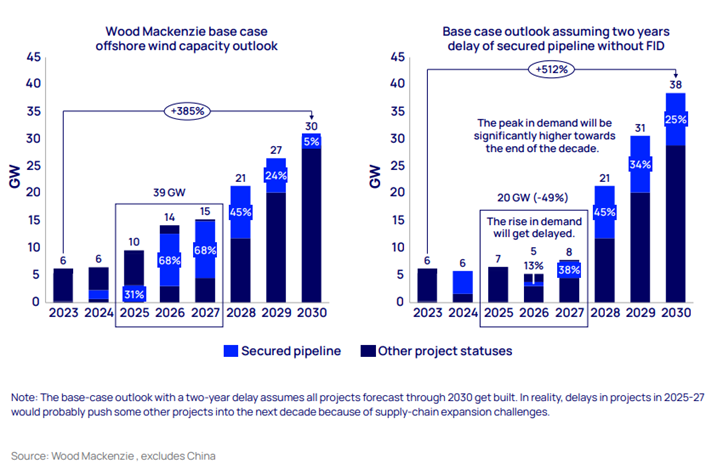

Some 24 GW of projects scheduled to come online between 2025 and 2027 have secured a route to market, through either some form of subsidy or power purchase agreement (PPA), but not yet made a financial investment decision (FID). This is the stage where developers look to firm up project orders with the suppliers, but multiple global projects now find themselves delayed as they look to renegotiate offtake contracts given increased supply costs and inflation.

Delaying projects at this stage will shift the anticipated equipment demand from 2025-27 to 2028-30. While the result would be less need for manufacturing expansion in the shorter term, there would be an even greater need for investment to expand to meet the demand from 2028-30.

Finlay Clark, Senior Research Analyst at Wood Mackenzie and co-author, said: “In reality, if this occurs, certain projects might not get built at all in 2028-30, meaning governments will risk falling further behind their targets. The uncertainty surrounding project timing is a large reason why supply chain participants hesitate to expand further.”

Many investors are concerned that if the supply chain were built out to satisfy peak installation demand in 2030, in order to meet government wind targets, there would be insufficient demand for equipment to support it after 2030.

“This seems eerily similar to the post-2015 drop in margins across the supply chain. This is an important consideration for suppliers, in particular, as they need to be confident in the demand 10-plus years ahead to earn a return on their investment,” Clark added.

How do we scale up?

Scaling up the offshore wind supply chain will require a number of adjustments by governments and developers. First, target setting and plans for power market infrastructure to support offshore wind need to extend beyond 2030 in places where they do not already do so. Other factors for policymakers to consider include the impact on the supply chain when deciding whether or not to renegotiate existing contracts and pausing the turbine size arms race with a size cap.

Finally, Soeren Lassen, Head of Offshore Wind at Wood Mackenzie and co-author noted: “It’s not all up to governments. Developers also need to consider innovative partnerships with suppliers to provide the demand stability that suppliers need to increase capacity.”

Offshore wind supply chain and policymakers need to pull together

“The sector – most notably the policymakers – must take this opportunity to chart a more sustainable path for offshore wind. This will not just influence the projects being installed today or in 2030, but also the 1.4 terawatt (TW) offshore wind capacity that Wood Mackenzie expects to be connected by 2050,” Seiple concluded.

Until very recently, China had developed its own supply chain, largely to meet its own demand. For this analysis, Wood Mackenzie has excluded projects and manufacturing facilities in China, unless otherwise specified. However, the report does look at how China could potentially factor into the larger global supply chain in the future.

About the report: ‘Cross currents: Charting a sustainable course for offshore wind’.

The offshore wind sector is navigating uncharted waters as it grapples with a fresh set of challenges in cost escalation and supply chain pressures. Much recent focus has homed in on a number of problematic projects in the US and UK. These projects won competitive tenders that locked in their remuneration schemes but have recently found themselves facing low projected returns due to unanticipated cost increases. Developers, used to declining costs for offshore wind projects, had assumed that these would continue, or at least not increase. These unwelcome headwinds have even prompted a few of the projects to halt development and pay contract termination fees for early exit.

This has left the offshore wind industry at a critical juncture. Dealing with such challenged projects is a real set-back for the industry and the energy transition. More importantly, however, they contribute to a larger issue lurking just around the corner ? ramping up the supply chain to meet developer and government objectives. These supply-chain challenges need to be addressed as a matter of urgency, as lead times on new manufacturing facilities are typically three to five years, with an additional one to two years until fully up and running. This edition of Horizons looks at these supply-chain constraints and the challenges and opportunities they present.