Nine artificial reefs were deployed during the construction of the Hollandse Kust Zuid (HKZ) offshore wind farm. Two years on, it’s time for a first stock-take.

Sytske van den Akker, a marine biologist at Vattenfall’s Environment and Sustainability Department, works with the ecological impacts of offshore wind farms.

“When you construct an offshore wind farm, you face all kinds of environmental and other permit requirements. For us, too, the environment is a concern when we build a wind farm. With this in mind, we’ve taken several nature-inclusive measures for the HKZ project to further boost biodiversity. We set out to explore biodiversity trends at three different stages: in 2024, 2028 and 2033, in order to gain an understanding of long-term development.”

Vattenfall recently became a partner in the KOBINE project, which compares the costs of nature-inclusive measures with benefits to nature.

“This not only gave us a great opportunity to share our knowledge and learn from other participants in this project, it also allowed us to join an expedition earlier than expected to inspect the reefs in the HKZ. “We’re monitoring the reef for the first time ahead of our scheduled research effort.”

For example, before a mature community of a particular marine species establishes itself in and around the reefs, it could take as long as six to ten years.

“So, the data we’re collecting now gives us a first indication of the biodiversity that may develop.”

All life leaves traces

The KOBINE project investigates the state of fish, shellfish, starfish, anemones and other animals in two ways: water samples and video.

“All marine life leaves traces of its DNA behind. Scale particles from fish, for example, or flakes from the shell of a crab. Those water samples are filtered and examined in the laboratory. We can successfully trace fish using this method, but we can’t yet identify all species as it doesn’t yet work equally well for all species groups. As the technology develops, we’ll be able to identify more and more species.”

“There are also developments that will soon allow us to say something about the numbers of a particular species present in an area. However, even now, it already provides a good indication of biodiversity, making animals that you can’t see from video surveys visible, for example. Moreover, the method is quick and doesn’t disturb marine life.”

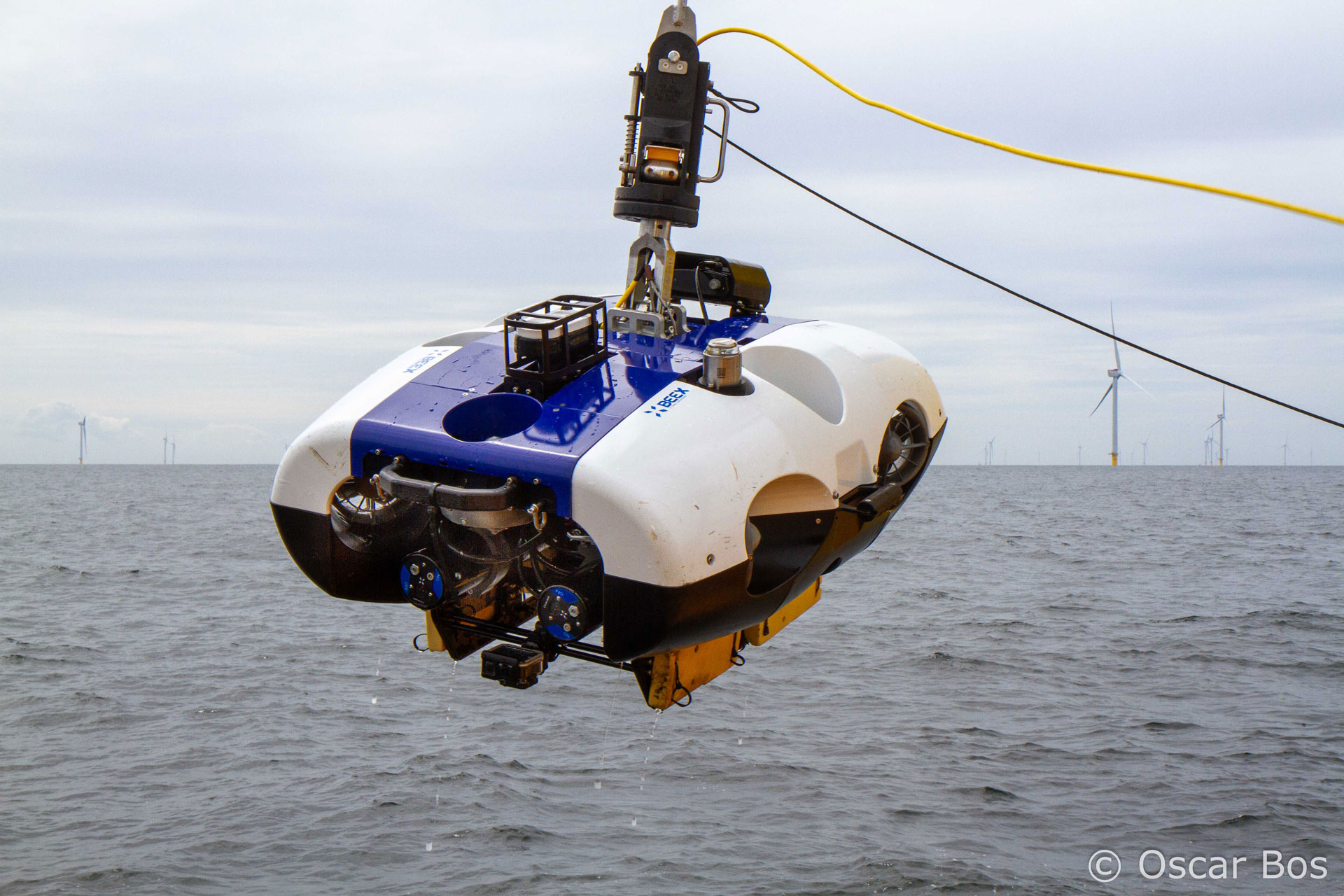

Video filming submarine

The other method of learning more about biodiversity on rocky reefs is to use video recordings.

“We use a small submarine for this purpose. Typically, we use an ROV, a vehicle that you operate remotely, but the KOBINE project has allowed us to use an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV). You can pre-programme it, and it will find its own way in the water. We were trying out one of these for the first time and we had a line of communication allowing us to follow device footage on a large screen on board. Being able to observe that marine life live was a special experience,” says Van den Akker.

Given the strong currents in the North Sea, tides play a major role in planning.

“As tides turn the current briefly becomes weaker than normal. This allows an AUV to easily sail against the current or stay put in a single place, meaning we get good image quality.”

The beauty of combining water sampling and video imaging is that these methods complement each other. On video, you see some species less clearly because sometimes the animals are really small, or they might be under a rock or swimming out of camera view. In addition, the water in the North Sea can be murky, making images less clear. Water samples provide important additional information.

“Of course, the most rewarding thing is when you measure something with DNA and you then spot the same species on the video, too”, says Van den Akker.

Using facts for the future

“I didn’t know exactly what to expect within just over a year of the artificial reefs being deployed, but I was pleasantly surprised. For example, there were already huge layers of mussels on the monopiles. And on the rocky reefs below, large anemones and starfish were already in existence, and we also saw many fish.”

Seeing that life on the sea bed with your own eyes like this is wonderful, but ultimately Van den Akker is all about getting the facts right.

“All the details of this project will be made public. The knowledge we are gaining now will be a useful asset when constructing wind farms in the future.”

KOBINE – nature-inclusive measures: costs versus revenue

KOBINE is short for Kosten en Biodiversiteit Natuurinclusieve Energie (Cost and Biodiversity Nature-Inclusive Energy). The KOBINE project looks at the cost of measures that help improve biodiversity and what they deliver for nature. The aim is to identify measures that are effective at a reasonable cost.

This project brings together De Rijke Noordzee, Wageningen Marine Research, Witteveen+Bos, Waardenburg Ecology and Vattenfall. Vattenfall provides access to the rock reefs.

By Clemens van Gessel