For a brief period over several weekends this spring, the state of South Australia, with a population of 1.8 million, did something no other place of similar size can hope to do: generate enough energy from panels rooftop solar panels to meet virtually all of your electrical needs.

This is a new phenomenon, but it has been happening for a while, since solar PV cells began being installed at a rapid pace across Australia in the early 2010s. About one in three Australian households, more than 3, 6 million homes now generate electricity nationwide. In South Australia, the most advanced state for rooftop solar, the proportion is almost 50%.

No other country comes close to installing small solar systems per capita. “It’s absolutely extraordinary by world standards,” said Dr Dylan McConnell, an energy systems analyst at the University of New South Wales. “We are way ahead.”

There was no overall plan to make Australia the world leader in domestic solar PV. Most analysts agreed that it was a happy accident, the result of a series of uncoordinated policies at all levels of government. Many were subsidy schemes that were derided as too generous and were gradually scaled back, but the most important – an upfront, easily accessible national rebate available to all – endured. It has helped make the panels cost-effective and easy to install.

Cost was a big consideration for the Jamiesons (Sean, Deb and their 19-year-old daughter, Molly) when they installed a system in their four-bedroom house in a beachside suburb in South Australia’s capital, Adelaide, ago. one of each. They upgraded to a larger 8kW system during a house renovation five years later, and installed two batteries, the first subsidized as part of a state government scheme testing home energy storage systems to help stabilize an electricity grid. which is increasingly powered by solar and variable wind energy.

Sean Jamieson, a pilot for airline Jetstar, said the setup had been “incredibly beneficial”, partly because his family uses a variety of energy-intensive equipment, including a swimming pool and hot tub. They first turned to solar energy after seeing the sharp rise in the price of grid electricity, mainly due to the cost of rebuilding electricity transmission poles and cables. He said it has continued to make sense.

“I’m looking at paying it off [through savings on what would otherwise have been annual energy bills] in three or four years, so it’s been a big investment,” he said of the home’s energy system. “Overall, solar is a no-brainer in South Australia. “We have lots of sunshine and the most expensive electricity in Australia, and at the beginning it was heavily subsidized.”

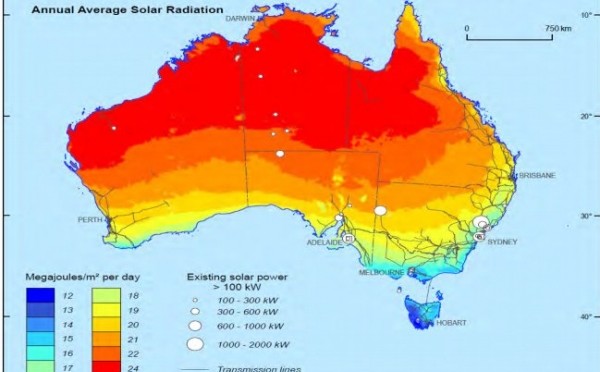

Dr Gabrielle Kuiper, an independent energy and climate change strategist, noted Australia was not the first country out of the gate on rooftop solar – that was Germany, which introduced the first subsidy scheme, and “none of us would be here without them” – but said it was one of the first to capitalise on the German model. It began with a natural advantage: more sun than nearly any other wealthy country. Even the southern island state of Tasmania is at a latitude that would place it level with Spain and California if it were in the northern hemisphere.

Kuiper said Australia had succeeded at solar for reasons beyond geography. Incentives were a big part of it, but the technology’s rise was accelerated by ordinary people embracing it to have some control over their power bills and, in some cases, play a small part in tackling the climate crisis by reducing the country’s reliance on coal.

The subsidies initially included a national rebate of A$8,000 for a small 1kW array – more than the sticker price in parts of the country. It was complemented by state government feed-in tariff schemes that paid households for the energy they fed back into the power grid and, in some cases, for all the electricity they generated.

There was little planning in how the various incentives fit together and critics attacked it as an expensive and inefficient way to cut greenhouse gas emissions. But it kickstarted an industry of installers, sales people, trainers and inspectors, and quickly made solar a viable option for people beyond the country’s wealthiest suburbs.

Today, the feed-in-tariffs have been cut, but the national rebate scheme survives, with bipartisan support despite deep divisions over other responses to the climate crisis. Analysts and industry players have praised its elegant design. The rebate is processed by and paid to the installer. The buyer may not even know it exists. It is reduced by about 8% each year, a rate that roughly keeps pace with the continuing fall in the cost of having panels installed.

The fall in cost has been significant. The sums vary depending on geography, but the SolarQuotes comparison site suggests many Australians can get a 6kW solar system for about A$6,000 (£3,100). The panels are likely to have paid for themselves within five years.

The influx of solar has brought challenges, including how to manage the flood of near-free energy in the middle of the day that risks making inflexible coal generators unviable before the country is ready for them to be turned off. Some states have responded by curtailing how much can be accepted into the grid, but Kuiper says this can be addressed through increasingly creative management. Answers include improving incentives for household batteries and fostering a two-way energy exchange between the grid and a growing electric vehicle fleet.

Rooftops provided 11% of the country’s electricity over the past year, part of a 38% total renewable energy share. The Australian government has set a challenging national goal of 82% of all electricity coming from renewables by 2030.

Simon Holmes à Court, a longtime clean energy advocate and convener of the political fundraising body Climate 200, said it was clear rooftop solar was playing a bigger part in reaching that than many people expected. “Not long ago renewables sceptics laughed at rooftop solar’s ‘tiny’ contribution. These days there’s no question solar is playing a major role in pushing coal out of our grid,” he said.

Tristan Edis, an analyst with the consultants Green Energy Markets, said the lesson for those watching on was pretty simple: the generous early subsidies worked. “It really was this fortuitous accident that happened,” he said. “The message from it is pretty clear: go hard and go big, or don’t bother.”

by Adam Morton