To synergize climate mitigation with poverty alleviation, China has implemented photovoltaic poverty alleviation (PVPA) projects since 2014, with Anhui Province being among the initial pilot regions. However, further exploration is needed to determine the extent to which this policy can improve the economic status of poverty-stricken areas. This study aims to evaluate the effects of PVPA projects in Anhui Province from a macroscopic perspective and via the panel data from 11 poverty-stricken counties, including 5 pilot counties, between 2011 and 2018. By employing the differences-in-differences (DID) model and synthetic control method (SCM) model, this study calculated the treatment effects of the PVPA policy. The analysis revealed that the policy did not significantly increase rural residential income at the county level. The insignificant treatment effects reflect a weak policy implementation. The PVPA policy tries to synergize the energy-climate-poverty nexus, requiring the coordination of various stakeholders and departments. Meanwhile, governance theory highlights the multivariate character of policy and considers the role of multiple social actors. Therefore, it is necessary to explore the governance factors when the policy implementation is weak. Further investigation of the PVPA projects reveals that the main governance challenges include insufficient motivation, information asymmetry, conflicts of interest, renewable energy curtailment, and the absence of proper maintenance and benefit distribution mechanisms. Considering the principles of good governance, recommendations for enhancing the effectiveness of the PVPA policy are proposed.

Introduction

As reported by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), the temperature in 2023 was approximately 1.4 °C above the pre-industrial level1. In light of the climate emergency, rapid and far-reaching transitions across all sectors are necessary to achieve deep emission reductions2. However, a timely energy transition should be integrated into more social agendas3. Achieving Agenda 2030 requires synergizing and resolving trade-offs between sustainable development goals (SDGs)4. The connections among the development of renewable energy, poverty reduction, and climate change mitigation create what is known as an energy-poverty-climate nexus5. Filho et al. (2023) described the synergies between these interconnected goals and climate action6. Despite widespread recognition and discussion of the relationship between energy and climate, Soergel et al. (2021) have highlighted a significant gap in the discussions on climate action and poverty alleviation7.

As the world’s most populous country and the most significant energy consumer and carbon dioxide emitter, China’s sustainable development and poverty reduction efforts are highly important. Recognizing the synergies within the energy-poverty-climate nexus, China has implemented photovoltaic poverty alleviation projects (PVPA) to combine renewable energy development with poverty reduction. Since 2014, Chinese energy regulators have announced an ambitious plan to help alleviate rural poverty by deploying distributed solar photovoltaic systems in poor areas. Anhui was chosen as one of the first batches of photovoltaic pilots8.

The policy analysis of China’s PVPA projects has focused mainly on the impacts evaluation and governance challenges. On the one hand, the positive effects of PVPA projects have generally been recognized9. For example, Xiao et al. (2023) noted that cost-benefit analysis indicates that community-based PVPA projects are cost-effective10. Li et al. (2024) found that the PVPA projects lead to an increase in per capita disposable income11. Moreover, the benefits for climate mitigation have also been confirmed. Wang et al. (2023) estimated that the cumulative carbon emission reduction benefits amounted to 636 million tons12. On the other hand, the effects of these projects are relatively weak because of governance defects. For example, using content analysis of policy instruments, Zhang et al. (2018) identified a need for more demand-oriented policy instruments for PVPA projects13. Scholars have noted obstacles to PVPA implementation, such as subsidy delays, insufficient infrastructure, low-quality equipment, and inflexible profit allocation mechanisms14. Wang et al. (2023) stressed the role of supervision and management in promoting the efficiency of the PVPA projects15.

However, the policy evaluations are mainly conducted from microscopic perspectives, such as the incomes of poverty-stricken families. Research that explores the effects of PVPA projects on residential income from a macroscopic level is rare. Moreover, quantitative analysis of the impacts of the PVPA projects on regional poverty alleviation needs to be expanded, and more discussions on governance issues are needed. In addition, the poverty reduction effect of the PVPA projects also shows strong regional heterogeneity16. Explorations at the provincial instead of the country level are also needed. The main research questions of this paper include whether the PVPA projects have significant and sustainable impacts on poverty alleviation and what the most challenging issues affecting its governance are. Based on a theoretical analysis of renewable energy and poverty alleviation and using the DID and SCM models, this paper aims to evaluate the effects of PVPA projects in Anhui Province, explore the governance challenges, and propose corresponding policy implications and recommendations.

Background

Theoretical basis

The implementation of PVPA projects reflects the energy-poverty-climate nexus5. The World Energy Council (WEC) proposed the concept of the energy trilemma to explain the inherent conflict of energy policy objectives17. The energy trilemma refers to the trade-offs among energy-related socioeconomic and environmental goals. Energy policies often fail to achieve the three goals of energy equity, energy security, and ecological sustainability. Although the energy trilemma reveals conflicts in energy development, the energy-poverty-climate nexus implies that renewable energy is a feasible choice for simultaneously realizing poverty alleviation and climate change mitigation5. Since a lack of access to modern energy services hinders poverty alleviation, access to clean, efficient, and sufficient energy sources is an essential complementary measure for alleviating poverty. As a result, energy security, climate change mitigation, and poverty alleviation can all be complementary, and their overlap defines an energy-poverty-climate nexus5.

Renewable energy sources can provide various socioeconomic and environmental benefits for sustainable development. Because energy is nearly related to all development goals, strategies that recognize the role of renewable energy solutions will, both directly and indirectly, benefit various stakeholders18. For example, renewable energy is conducive to diversifying the energy supply, creating employment opportunities, and expanding income sources while emitting much fewer GHGs than fossil fuels and reducing health risks. However, the synergizing energy-poverty-climate nexus faces many challenges. First, the components of this nexus are related to various departments and stakeholders. A public-private partnership model that integrates the government, corporate, and civil society is needed19. The coordination and interest balance are challenging. Second, impoverished groups generally lack the economic, technological, and political capacities to secure their interest in the process of PVPA projects. Third, as a policy innovation, implementing PVPA projects or other similar projects requires more institutional and legislative support. These defects will negatively affect the efficiency of synergizing the energy-poverty-climate nexus through PVPA projects. As a result, it is necessary to evaluate the performance of PVPA projects in practice and identify the need for improving governance.

PVPA pilots in Anhui Province

The development of infrastructure construction provides an opportunity to eliminate energy poverty. It is estimated that less than 60% of the population in China has access to clean cooking, which increases the emissions and health risks. Residents in energy-poverty areas mainly use biomass fuels and cheap coal for heating and cooking to reduce energy expenditures20. PVPA projects refer to using photovoltaic power generation to provide a new model for poverty alleviation. It is a type of industrial poverty alleviation. As a significant source of clean and renewable energy, solar energy helps mitigate the adverse effects of climate change. It avoids releasing greenhouse gases and other pollutants from fossil fuel combustion. Since 2009, the implementation of photovoltaic construction projects has promoted the rapid development of photovoltaics. Photovoltaic power generation projects have sprung up everywhere and have also played a role in rural development and construction. In 2014, Yuexi, Funan, Sixian, Jinzhai, and Lixin, five poverty-stricken counties in Anhui, were chosen as the first batch of PVPA pilots. On March 9, 2015, the New Energy and Renewable Energy Department of the National Energy Administration issued the Outline of the Implementation Plan for PVPA projects, which stipulates that local governments should provide 35% investment subsidies for household and agricultural facility-based PV poverty alleviation projects and 20% investment subsidies for large-scale ground power stations, while the central government will allocate initial investment subsidies according to the same proportion; household and agricultural facility-based PVPA projects will be repaid for five years and enjoy a total discount of banks, and large-scale ground power stations will have a repayment period of 10 years.

The implementation of PVPA projects results from the requirements of various tasks or strategies in China. Poverty reduction, rural revitalization, energy revolution, and climate change mitigation are the main drivers of the PVPA projects. According to statistics disclosed by the National Bureau of Statistics, there were still 584 poverty-stricken counties in China by 2019, and 5.51 million people in rural areas still live in poverty21. Furthermore, relative poverty remains a serious social challenge. Townsend defines relative poverty as the lack of resources to obtain the types of diet, participate in activities, and have living conditions and amenities customary or at least widely encouraged and approved in the societies to which they belong22. More work is needed for China to narrow the income and welfare gap between different groups and regions.

Methods

To evaluate the effects of PVPA projects on poverty reduction, this study uses annual data at the county level to analyze the relationship between rural residents’ income (income) and the implementation of PVPA policies. Previous studies have stressed the price of agricultural grains, industrial development, rural education level, and local financial capacity as the main factors affecting rural residents’ income. For example, Peng et al. (2022) noted that raising the price of grain is necessary to increase farmers’ income23. Upgrading the industrial structure is conducive to narrowing the urban-rural income gap at the country level, but the effects have regional heterogeneity24. Rural residents with more education will obtain more opportunities off the farm and more favorable labor market outcomes25. In addition, public expenditure and economic growth are important for poverty alleviation26. Financial income (FI), financial expenditure (FE), industrial rate (IR), rural education level (EDU), and the minimum purchase price of wheat (MP) are included as control variables. This paper used related data from Anhui Province from 2011 to 2018, where five counties were chosen between 2014 and 2018 as PVPA pilots. The rural residents’ income data was obtained from the Anhui Statistical Yearbook (2011–2018). The data for the last four items were collected from the China Statistical Yearbook (County-Level) from 2011 to 2018. The income data, FI, FE, and MP, are converted to logarithmic forms to eliminate possible heteroscedasticity. The DID model is used to evaluate the implications of the PVPA projects for income. Then, specific treatment effects were calculated via the synthetic control method (SCM).

DID model

As a widely used policy assessment method, DID quantifies a policy’s causal effect by comparing the treatment group with a control group before and after an intervention. It can effectively control research subjects’ prior differences and isolate the policy’s actual intervention effect13. In a panel data structure framework, the study measures the differences between the treatment and control groups in the outcome variable that occur over time. The baseline case for DID is the one with two periods. The observed outcomes are given by:

(1)

Where represents the period before treatment and is the period after treatment. is unit ’s untreated potential outcomes before treatment. is unit i’s untreated potential outcomes after treatment. is unit i’s treated potential outcomes after treatment. is for units in the treated group, and

is for units in the untreated group.

The main parameter of interest in most DID designs is the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT). It is given by:

(2)

The DID method identifies the ATT under the parallel trends (PT) assumption. The parallel trends assumption states that the trends in outcomes between the treated and comparison groups are the same before intervention.

(3)

………

Furthermore, the DID regression technique can provide the same estimator and the significance level27. The two-way fixed effects Regression (TWFE) is the most common approach to estimating the effect of a binary treatment.

(4)

Where is the constant item. and represent the estimated parameter. is the core estimation parameter, representing the average effect of participating in the treatment. . represents the region dummy variable. indicates the control group, and indicates the treatment group. represents the time dummy variable. means before treatment, and means after treatment. represents the control variables. and represent the county-fixed effect and time-fixed effect, respectively.

is the perturbation term.

The samples from Anhui province are divided into two groups. The treatment group comprises five pilot counties: Yuexi, Funan, Sixian, Jinzhai, and Lixin. To compare poverty reduction progress and evaluate the effectiveness of PVPA policies, six other poverty counties at the state level in Anhui were selected into the control group. The PVPA projects implemented in 2014 are taken as a quasi-natural experiment, and the DID model is used for policy analysis.

The model is as follows:

(5)

Where represents the rural residents’ income of county in period . is the average treatment effect estimator after PVPA projects implementation. for the 5 poverty-stricken counties after 2014, while

in other situations.

SCM model

SCM is most commonly used alongside DID methods28. Abadie and Gardeazabal (2003) proposed the SCM to overcome the limitations caused by the DID method29. SCM has several advantages over alternative approaches to evaluating policy interventions. First, it offers an approach suitable for a small number of treated and control units. Second, unlike DID approaches, SCM does not rely on parallel trends before implementation. Finally, SCM allows for unmeasured time-varying confounders, whereas DID only allows for measured time-varying confounders29. According to the different objects in the control group, the weights are given, respectively, and a composite control group is created by the weighted average method. The difference between the intervention group and the hybrid control group is the influence of policy intervention30. Suppose the outcome variables of counties and periods are observed, the th county was affected by PVPA in phase, while other counties were unaffected. It belongs to the control group to be synthesized. The treatment effect of PVPA on county

is expressed as:

(6)

Where represents farmers’ income, while 1 and 0, respectively, indicate whether the county is affected by PVPA. Assuming that

represents the dummy variable of whether PVPA impacts it, the model can be further set as follows:

(7) represents the treatment group’s income after being affected by PVPA. When t?>?T0, is the income before the PVPA and cannot be directly observed and it is needed to construct a “counterfactual variable” to represent

. The model is as follows:

(8)

Where represents the time-fixed effect. indicates an unknown parameter. represents the observable variable that is not affected by PVPA. stands for common attractor. is the fixed effect.

expresses a temporary shock. Based on Eq. (8), the policy treatment effect can be obtained so that the specific impact of PVPA on each county can be evaluated.

Results and discussions

Baseline regression results

Table 1 shows the baseline regression results. The coefficients of range from 0.0242 to 0.5642, reflecting a positive correlation between the PVPA projects and an increase in farmers’ income. However, all of the coefficients of in Models (2) to (4) are insignificant. The coefficient of in Model (1) represents a 75% average increase after intervention. Although the coefficient of in Model (1) is significant, the of this model is only 0.3800, which means more variables should be included to provide more reliable estimations. The results also show that local finance can significantly affect farmers’ income in Model (3). Local financial income and expenditure reflect economic development in general and the local government’s ability to improve facilities and social welfare for farmers in their jurisdiction. Specifically speaking, an increase of 1% in financial revenue and expenditure will increase rural residents’ income by 0.2273% and 0.4753%, respectively. The two coefficients also reflect that public expenditure has a greater impact on poverty alleviation. The expenditure will generally provide more infrastructure (such as roads, irrigation, power, transport, and communication) needed for development in rural areas. The rate of industrial added value in the total gross domestic product remains stable during the sampling years and only has a slightly negative effect on farmers’ income in Model 3. This means that the slow industrialization process in impoverished counties has little impact on rural residents’ income. Their income is mainly from agriculture. This is also proved by the coefficients of the price of wheat, which are all significant in both Model (3) and Model (4) at the 1% level. In a regional fixed effect model, a 1% increase in the price will cause a 0.8211% increase in income, whereas a 3.6592% increase will occur when considering the time-fixed effect. The coefficients of

are 0.0242 and 0.0257 in Model (3) and Model (4), respectively, representing a nearly 2.5% average increase in rural residents’ income after implementing the PVPA project. However, the coefficients are insignificant even at the 10% significance level. Therefore, the PVPA policies have not significantly improved the economic status of farmers, and the path-dependency of farmers’ livelihoods has not been heavily shocked by the industrial poverty reduction projects through the PVPA.Table 1 Baseline regression results.

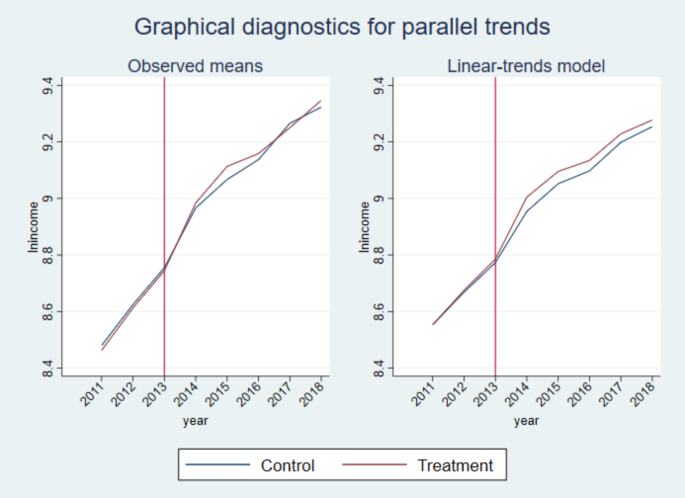

Parallel trend test results

The parallel trend hypothesis is an essential premise of the differences-in-differences model. It should be affirmed that pre-intervention trends in outcomes are the same between treated and comparison groups. The parallel test was conducted in Stata 17 after DID regression. The null hypothesis is that linear trends are similar. Through the parallel-trend test, the sample’s value is 0.7500, and the

is 0.3909. This indicates a parallel trend existed between the treated and comparison groups before PVPA implementation. The trends of the control and treatment groups can be seen in Fig. 1.

SCM results

The PVPA pilots in Anhui consist of five counties, each with its own unique socioeconomic context. There are variations in the effectiveness and impact of PVPA implementation among these counties. This paper employs the SCM model to examine these differences by assessing the specific treatment effects for each county. The average treatment effects for the pilots are presented in Table 2.Table 2 The average treatment effects over the post-treatment period.

The most significant treatment effect is 0.0582, reflecting a 5.99% increase in income compared with the synthetic outcome of Lixin County. Yuexi County experienced a 5.41% increase after the policy intervention. The highest treatment effect in Funan, Sixian, and Jinzhai is 0.0201, representing an increase of nearly 2.03%. The average treatment effect of the five counties is 0.0303, which means an average increase of less than 3.12%. However, the results’ regional heterogeneity and relatively small value indicate less significant impacts of the PVPA policies.

The inconsistent and insignificant efficiency reflects a weak policy implementation. It is recognized that policies do not succeed or fail on their own merits but rather in the implementation process31. Governance issues are directly linked to policy implementation. Governance theory highlights the multivariate character of policy and considers the role of multiple social actors32. Governance structures are necessary to guarantee and implement rights and duties when coordinating transactions33. Therefore, synergizing climate change mitigation, renewable energy development, and poverty alleviation requires good governance institutions.

Governance factors affecting PVPA efficiency

Due to the relatively immature governance institutions and the particular political and economic contexts, the PVPA pilots have not sufficiently realized their potential. Based on the evaluation of PVPA projections in Anhui and related literature and investigations, the following challenges and barriers during the implementation of these projects have negatively affected their efficiency, expansion, and sustainability.

Insufficient motivation for implementation

The initial investment of photovoltaic power generation projects constitutes the main cost during their whole life cycle. As renewable energy is generally less competitive than traditional energy, the cost always exceeds the affordability of low-income groups. Moreover, enterprises are only willing to take risks with sufficient subsidies and access to the grid. As a result, the current existing PVPA projects mainly depend on the government’s investment.

The PVPA projects are only possible with governmental funds because of the need for initial investment. In addition to excessive reliance on government investment, subsidies account for a large proportion of the income from these projects. It is estimated that approximately 2/3 of the payment is from subsidies. If the subsidy policy changes, such as through reduction or even cancellation, or if the subsidy cannot be fully and timely distributed, the poverty-alleviating effect and sustainable development of PVPA projects will be negatively affected.

However, raising funds for PVPA projects requires a solid and lasting political will. The development and maintenance of PVPA projects involve a heavy financial burden, and the government needs more motivation to maintain them continuously.

Fraud caused by information asymmetry

PVPA projects involve various actors and information. Because they are limited by their economic and educational ability to obtain sufficient information about the details of those projects, people in poverty tend to be passive acceptors. The information asymmetry herein has created opportunities for illegal actions in PVPA projects.

Since PVPA projects involve a tremendous amount of subsidies and investment, the government and low-income people have been victims of fraud in various forms due to information asymmetry. Regarding government subsidies, some companies defraud related funds through fake contracts or false data. For example, in 2016, the National Audit Office of China verified that 38 of the 45 sub-projects of the Xiangxi Lantian company had different problems and were suspected of defrauding 266 million yuan of subsidy funds from the Golden Sun project. Among them, 16 projects had yet to be installed or reported more installed capacity. In addition, 15 projects were not connected to the grid for electricity generation after installation, and the equipment was left idle or subsequently dismantled, involving an installed capacity of 14 megawatts and a subsidy of 61.84 million yuan34.

Market obstacles due to conflicts of interest

In China, the power grid, the sole buyer of power from power plants and the exclusive seller of power to consumers, has a monopoly from transmission to sales. The grid could be more enthusiastic about the power grid connection of new energy and even hinder the relationship of renewable energy. Even if they are all connected and sold to the grid, the cost of generating electricity from unknown sources is several times higher than that from traditional sources. Even with state subsidies, it is not cost-effective for the grid to buy and sell renewable electricity. What’s more, more infrastructures have to be constructed. As a result, the grid has less incentive to purchase electricity generated from renewable energy. Furthermore, energy regulators are leading the projects, and as an extension of their traditional energy management function, their motivation for poverty alleviation is limited35.

Despite the rapid development of renewable energy in China, the problem of renewable energy curtailment has yet to be effectively solved. The implementation of PVPA projects will also be significantly affected by the overall development context of renewable energy. Currently, China’s clean energy consumption faces the following difficulties:

- The reverse distribution of resources and demand limits the efficiency of electricity consumption. Most scenery resources are distributed in the northern region. At the same time, the electricity load is located mainly in the central, eastern, and southern areas, resulting in more significant inter-provincial transmission pressure.

- The rapid development of renewable energy is different from the growth rate of electricity consumption in recent years. With the active support of national policies, the installed capacity of renewable energy, especially wind power and photovoltaic power generation, has maintained a fast growth rate, far exceeding the growth rate of society’s electricity consumption.

- Wind and photovoltaic power generation is affected by natural conditions and is relatively volatile. Large-scale grid connection brings significant challenges to the dispatch and operation of the power systems36.

Renewable energy curtailment has aggravated the difficulty of selling electricity produced by PVPA projects. Access to the grid and market is necessary for sustainable income to exist. The poverty alleviation target through renewable energy will not be achieved, and the investment will become a new burden for people experiencing poverty.

Absence of proper maintenance and benefit distribution mechanisms

The maintenance of PVPA facilities is critical for the performance of related projects. If the maintenance is improper or neglected, it will shorten the efficiency and life of the project. If sustainable development strategies are implemented to promote poverty reduction in remote rural areas, robust technology, adequate maintenance, and financing strategies are needed37. Centralized PV power plants are generally installed in remote areas, which makes them difficult to monitor. Moreover, household-distributed power plants are scattered, so the maintenance and management of PVPA projects are more complex. In addition, maintenance requires relatively stable professional and technical teams, but poor areas need more personnel resources. However, many local governments usually emphasize construction, and there needs to be a clear explanation or regulation for the operation and maintenance of PVPA projects.

The income distribution mechanism of existing PVPA projects is another thorny challenge. Poor households nominally own the income of the household power generation system. Nevertheless, some low-income families also need to use the payment of power generation to repay enterprise advances or bank loans, which leads to the final income of some poor households being lower than expected. The income from power generation at the village level is distributed proportionally by village collectives and low-income families, but there are also some drawbacks to this distribution mechanism: first, it is easy to cause low-income but non-poor households’ objections to related projects; second, it is difficult to ensure that low-income families obtain a reasonable income. Without a proper income distribution mechanism and effective supervision mechanism, even if the PVPA projects can make an expected profit, it is still uncertain whether or not they can accurately benefit poor households or to what extent they can accurately benefit low-income families.

Policy implications

As the government has provided advantageous policies for PVPA projects, a proper institution is needed to ensure that those policies can be effectively and efficiently implemented. Poverty is considered to be closely connected with institutions. Institutions reflect the way of governance, whereas governance relates to ideas about political power, economic and social resource management, political processes, personal rights, and the relationships among the government, the market, and the general society38. Good governance is a determining factor for poverty alleviation and development39. Several criteria are proposed to evaluate good governance, including transparency, accountability, predictability, democracy, respect for human rights, and the rule of law. The problems and challenges facing China’s PVPA projects are closely related to the lack and irrationality of institutional arrangements, which are reflected in the neglect of their sustainability and potential risks, the excessive pursuit of short-term alleviation of poverty, and the failure to pay attention to the prevention of many illegal acts in the process of project implementation. Poverty alleviation is a systematic project that cannot be solved by government investment alone. The society’s overall political and economic background affects its effective and sustainable implementation. It must be implemented and continuously promoted by practical governance mechanisms to fully use renewable energy in poverty alleviation, climate change combating, and energy security enhancement.

Expanding the function and value of PVPA projects

Rural electrification through grid extension is most viable when the principal focus is facilitating productive applications instead of simply providing social services such as street lighting and improved health and education services. For example, the “PV?+?modern agriculture” mode combines PVPA projects and modern agriculture. The rural economy mainly comes from the production, processing, and marketing of primary outputs. The electricity from PVPA projects can be used to improve the efficiency of agriculture40. The other is the “PV?+?carbon trade” mode. A carbon market can compensate for the positive externality of PV projects, and it will transform environmental effects into economic benefits, bringing more income to poor areas while protecting the ecological environment and improving the efficiency of renewable energy utilization41.

In addition, implementing the project requires a proper combination of government and market mechanisms. To realize the economic value of carbon reduction from PVPA projects, China should accelerate the construction of green energy markets, such as environmental taxes and green certificates, internalize the environmental costs of fossil energy, such as coal, and gradually replace fossil energy with wind and solar power through market regulation42.

Improving transparency of related policies

The policies regarding the construction and subsidies for PVPA projects should be well-known to low-income people. Communication and transparency are significant barriers to renewable energy deployment. However, some areas in China have yet to make public poverty alleviation funds and implementation processes for projects, and the channels of public disclosure and publicity among rural people are limited. Some places only make public announcements at the level of township and village committees or substitute public statements with meetings. In addition, people experiencing poverty generally need more resources to get information, and some are also incapable of understanding the financial arrangements and risks of the projects.

To overcome information asymmetry, the government should consider the costs of policy transparency. Owing to the various effects of energy policy, the energy sector cannot decide on the policies alone. A cooperative and multi-sectoral approach to energy policy formulation and implementation will be constructive for poverty reduction43. During this process, primary-level organizations and grassroots organizations play essential roles. Public participation in decision-making is necessary for improving transparency44. The government should ensure that people with low incomes understand related policies through extensive publicity and education and encourage social actors such as volunteers to improve the transparency of the guidelines.

Increasing the level of the rule of law in renewable energy poverty alleviation

Poverty alleviation by renewable energy involves the redistribution of interests and adjustment of existing claims. It is imperative to consider institutional inertia and resistance from vested interests. The rule of law is the key to ensuring its effectiveness. As renewable energy poverty alleviation is related to renewable energy development and poverty reduction, laws regarding the two fields need to be implemented. The Renewable Energy Act 2005 is a typical law for renewable energy development, but there are no rules about poverty reduction through renewable energy. The Renewable Energy Law provides grid access for renewable energy, but institutional capacity needs to be developed to interpret and implement the law. For example, the fully guaranteed acquisition institution stipulated by this act could be more effective. Furthermore, detailed rules for constructing and maintaining renewable energy poverty alleviation projects are also required.

Thus, the rule of law should be guaranteed if the blooming of renewable energy development is pursued. Since the main target of those projects lies in poverty reduction, the legal rules should mainly stipulate laws regarding poverty reduction. However, there is no law specifically regulating poverty reduction in China. Thus, a Poverty Reduction Act is urgently needed to secure the implementation of poverty reduction measures, including those through renewable energy development.

Establishing proper maintenance and benefits distribution mechanisms

Considering the technical and economic requirements of PVPA facility maintenance, the installation enterprise is responsible for the maintenance services, including power generation equipment maintenance, daily maintenance training, and issuing maintenance manuals for the installation households. Specific maintenance teams in related villages or counties are also needed, with operation funds provided by the installation enterprise. These teams can provide employment opportunities. In addition, insurance for accidents and equipment quality can mitigate related risks and improve acceptance of PVPA facility installation and operation. The power generation income of village-level PVPA power stations is owned collectively and used to provide job opportunities, develop infrastructures, and relieve subsidies. The benefit distribution mechanisms should stipulate the collective and households’ share. The distribution and expenditure arrangements should also be determined with transparency and supervision.

Effective control over fraud and corruption by grass-roots village committees in poverty alleviation is urgently needed. As Amartya Sen noted, exchange entitlements play an essential role in poverty, and civil and political rights are necessary for promoting effective development and growth18. In China’s rural areas, the factors that significantly impact the exchange entitlements lie in the villagers’ right to participate and supervision. The government needs to place more importance on supervising rural management and improving the awareness of the rights of low-income people.

Conclusions

The PVPA projects have the potential to integrate the energy-climate-poverty nexus, but their success depends on ensuring high implementation efficiency and avoiding more economic risks and burdens for the poor. This issue involves dealing with the correlations between implementation and governance. The PVPA policy has a good policy vision, but it needs to overcome government failure, market failure and governance failure caused by inadequate incentives, asymmetric information, imperfect legal provision and unbalanced interests based on the principle of good governance. Good governance is evaluated based on transparency, accountability, predictability, democracy, respect for human rights, and the rule of law. The challenges are largely due to the lack of rational governance institutional arrangements. The successful implementation of these projects is influenced by societal, political, and market factors. Institutions should adhere to the principles of good governance and undergo political reforms in rural governance to commercialize village-level renewable energy projects successfully. This will enable the synergistic effects of renewables in combating climate change and reducing poverty. This study expands the literature on China’s PVPA projects from a macroscopic perspective and explores the governance challenges. However, this study has limitations in sampling distribution, and more qualitative data is needed to explore the views of various stakeholders. Future studies should consider expanding the sample size to validate the findings and improve generalizability. Additionally, qualitative methods such as in-depth interviews can provide deeper insights into the implementation and governance issues in the PVPA or similar projects.

Scientific Reports volume