To achieve carbon neutrality, solar photovoltaic (PV) in China has undergone enormous development over the past few years. PV datasets with high accuracy and fine temporal span are crucial to assess the corresponding carbon reductions. In this study, we employed the random forest classifier to extract PV installations throughout China in 2015 and 2020 using Landsat-8 imagery in Google Earth Engine. The results were further visually inspected and refined by morphological filtering, cavity filling and manual adjustment. Validation analysis revealed that the initial classification achieved an overall accuracy over 96% for both 2015 and 2020. Further validation using independent test samples demonstrated that the final dataset outperformed the accuracies of existing PV datasets. In 2015, the total area of installed PV in China was 663.09?km2, which were mainly distributed in the northwest, Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei, and the Yangtze River Delta region. By 2020, the total area of PV reached to 2847.36?km2, with net increase of almost 3.3 times. Installed PV was intensified in the northwest and extended to eastern China.

Background & Summary

The accumulation of carbon dioxide resulting from the combustion of fossil fuels has contributed to global warming1,2. In order to achieve the goal of carbon neutrality, vigorous development of renewable energy has become a common goal for many countries in the world3. Solar energy is the most common renewable energy source that is clean, safe, and inexhaustible. It has a great potential to replace fossil fuels4,5. Photovoltaic (PV) technology utilizes solar panels to convert solar energy into electricity without the need for any thermal engines6. With the advancement of PV technology and the reduction of PV power generation costs, the number of PV installations has rapidly increased worldwide7. China is the largest and fastest-growing country in terms of PV installed capacity8. By the end of 2022, China’s cumulative installed PV capacity had reached 392.6?GW, with an additional installation of 87.41?GW in 2022 (National Energy Administration, 2023), ranking the first globally in terms of new installation rate. It has become the world’s largest PV power market, accounting for nearly one-third of global PV installations9. Therefore, understanding the details of existing PV installations and their development over time plays a crucial role in predicting PV power generation, assessing its environmental impact and carbon reduction benefits, and future PV industry planning.

There have been several regional, national and global scale PV distribution products derived from satellite remote sensing images at a certain year. Compared to household surveys and utility interconnection filings, remote sensing technology has advantages in obtaining the spatial and temporal information about PV development8. For instance, Kruitwagen et al. used deep learning methods and large-scale cloud computing infrastructure to provide a global inventory of commercial, industrial, and utility-scale solar installations from open satellite images10. Stowell et al. publicly released a PV dataset covering over 260,000 solar installations in the United Kingdom11. Zhang et al.12 combined machine learning and visual interpretation methods to map PV power plants in China in 2020 using Landsat 8 surface reflectance images. Yu et al. proposed the DeepSolar framework to map PV panels from very high resolution satellite imagery and created a comprehensive PV installation database of the contiguous US13.

However, none of the above studies provided multi-temporal PV distribution. In reality, PV installations are deployed at an unprecedented pace as introduced above. Multi-temporal PV datasets are very useful to analyze the spatial pattern of the development of PV industry. Wang et al. developed the DeepSolar++ model to identify the installation year of PVs from historical aerial and satellite images across 46 US states over the year 2006 to 201714. Xia et al. extracted the distribution of PV installations in northwestern China from 2007 to 2019 using Landsat images15. Unfortunately, their study only focuses on the five north-western provinces in China. Most recently, Chen et al. employed the TransUnet model to extract PV installation in China from Sentinel-2 images in the year 2022. Afterwards, the installation date was estimated by analysing the time series data of Landsat 5/7/8/9 within each extracted PV area. However, this method only detects PV installations which still exist in the year 2022, while failing to extract PV that once existed but dismantled before 2022. In addition, out of 138 test sites, their method correctly estimated the installation time in 124 sites, while producing wrong estimates in 14 sites (about 10%). Therefore, extracting PV using historical satellite images may be more appropriate to analyze the spatial-temporal distribution of PV development.

In this study, we aim to extract PV distributions across China in the year 2015 and 2020 using open satellite imagery. The release of this dataset can provide valuable references for researchers and users in the fields such as renewable energy, remote sensing, geography and environment sciences. The potential applications of this dataset include (1) analysing the spatial and temporal patterns of PV installation across China over different land cover and land use types; (2) providing PV samples in China which can be further used to train a deep learning model; (3) estimating the generated electricity and carbon mitigation effect from solar PV; (4) evaluating the environmental impact of PV on hydrology and local climate; (5) offering reference for future national and provincial energy planning.

Methods

The overall workflow includes satellite image compositing, sample collection, feature extraction, PV classification, post-processing, accuracy assessment, consistency evaluation and statistical analysis. As follows please see detailed descriptions.

Study area

China is located in East Asia along the western coast of the Pacific Ocean. It has a vast territory with a total land area of 9.6 million km2 and diverse land cover types. The terrain of China is characterized by a stepped distribution, with high mountains in the west and low plains in the east. Across the expansive and fertile land of China, solar energy resources are abundant, with most regions having an annual average daily solar radiation of over 4 kWh/m2 and more than 2,000?hours of annual sunshine in over two-thirds of the country16. The amount of solar radiation reaching the surface of the Earth in China in the year 2020 is displayed in Fig. 1. It can be observed that solar radiation is quite abundant in western parts of China. As the world’s largest carbon-emitting economy, China plays a crucial role in global low-carbon transition17. Since 2007, China began vigorously developing the PV industry. Due to the vast territory, complex environment and diverse land cover, China has developed various types of PV installations, including rooftop PV, fishery-solar complementary systems, desert PV plants, as well as agrivoltaic farming.

Satellite imagery

Landsat satellite images were employed for analysis as it has the longest observation record of the earth surface. We utilized the Landsat-8 atmospherically corrected surface reflectance product (LANDSAT_LC08_C02_T1_L2) on the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform, which has a spatial resolution of 30?m. The product has been atmospherically and geometrically corrected. Pre-processing operations were performed on this product including cropping, temporal filtering, and de-clouding of the images across China. We filtered images with cloud cover greater than 10% and then composited the cloud-removed images into one using the median value of each pixel for both years. The final remote sensing images of China were synthesized for the whole year of 2015 (January to December) and 2020 (January to December) respectively. We chose the year 2015 and 2020 for PV mapping due to the following reason. After examining the development history of China’s PV industry, we can observe that prior to 2015, the cumulative PV installed capacity in China remained consistently below 50?GW. However, since 2016, this figure surpassed the milestone of 77?GW, indicating rapid growth after 2015. By the year 2020, China’s cumulative PV installed capacity has exceeded 253?GW. Therefore, we adopted the year 2015 and 2020 for analysis.

PV extraction

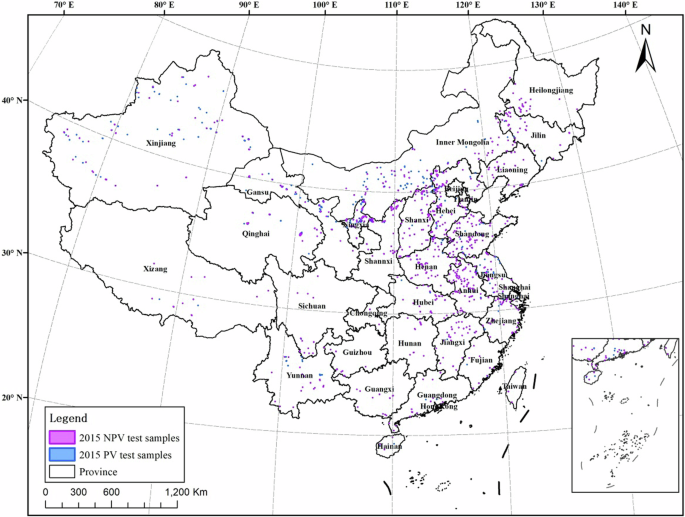

- Training and test samples for PV detection The study area was classified into two land cover types, i.e PV and none-PV (NPV). We used a stratified random sampling method to collect the PV and NPV samples. First, in selecting the PV samples, 4000 PV sample points were randomly generated across the country based on the 2020 China PV plant atlas published by Zhang et al.12. For these random points, a rectangular buffer area of 60?m?×?60?m was created. In addition, we visually inspected each sample with the help of high-resolution satellite images available on the Google Earth Pro platform, and retained 3975 polygons as PV samples. As for NPV, we generated 6800 random points based on the ESA land cover product CCI-LC202018 and constructed a 90?m?×?90?m rectangular buffer as NPV samples. Afterwards, 70% polygons were randomly selected as training samples and the remaining 30% were used as test samples. The spatial distribution of training and test samples for both PV and NPV in the year 2020 is shown in Fig. 2. As for the year 2015, we only selected test samples because we directly applied the previously trained classifier in 2020 to the year 2015. A total of 700 PV sample points were randomly generated across the country based on the global PV inventory published by Kruitwagen et al. Since their dataset were published in 2018, we visually checked whether each PV existed in 2015 with the help of historical satellite images on Google Earth Pro. A total of 676 polygons as PV samples were retained. As for NPV, we generated 1324 random points based on the ESA land cover product CCI-LC2015. The distribution of test samples for 2015 is shown in Fig. 3.Fig. 2

(a) The distribution of training and test samples for both PV and NPV objects in China in the year 2020; (b–d) examples of PV installations; (e–h) examples of non-PV objects.Full size imageFig. 3

The distribution of test samples for PV and NPV objects in China in the year 2015 (Note: the random forest classifier was trained using samples from 2020).Full size image

- Random forest classification We used the random forest (RF) classifier on GEE to classify the Landsat image composites into PV and NPV classes. The RF classifier is a widely used machine learning algorithm that can effectively handle high-dimensional data as well as multiple covariance feature problems with strong model generalization and good classification performance19. When using the random forest classifier, we set the number of trees to 100 and keep the remaining parameters as default values. Among these parameters, the minLeafPopulation is set to 1, and the randomization seed is set to 0. In this study, 16 variables were selected as classification features. These include 7 raw bands, 3 computed indices, and 6 texture features. The seven raw bands include the surface reflectance of four visible bands (B1, B2, B3, B4), the near-infrared band (B5), and the two shortwave infrared bands (B6, B7). In addition, three indices include the normalized difference built-up index (NDBI)20, normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI)21, and modified normalized difference water index (mNDWI)22 were adopted as suggested from previous studies23. In addition, we also incorporated the “sum average” texture of the B2, B6, B7, NDBI, mNDWI, and NDVI into classification as previous studies found that texture features can improve the detection accuracy of PV23,24. These classification features were used as variables to train the random forest classifier to distinguish between PV and NPV.

- Post processing

As the initial classification was conducted on a pixel basis, pepper noise occurred in the results. In order to remove these misclassifications, a series of post-processing operations were performed on the initial classification results to refine the detection of PV.

Firstly, we conducted morphological opening using a circular kernel with 1 pixel radius on the PV classification results on the GEE platform to filter out speckle noise. In addition, PV installations are more likely to be located near human-inhabited areas rather than in desolate and uninhabited areas in order to reduce energy losses in the transportation of electricity. Utility-scale PVs may be a bit far away from human-inhabited areas as it prefers flat areas, abundant solar potential, and cheap land. Nighttime light data from satellite observations can provide a visual representation of humans on Earth25. Therefore, we used the VIIRS nighttime light data to filter the classification results after morphological manipulations to eliminate PV detection errors in uninhabited areas. City limits were extracted by setting an intensity threshold (>3) on the nighttime light radiance products and a 20?km buffer zone was generated around the extracted city area to filter the initial classification results26.

Afterwards, we exported the PV extraction results from GEE to local hard drive as polygon vectors. Last but not least, we performed further post-processing operations on the exported PV polygons to refine the contours of each PV. It was found that some PV installations appeared as small patches or having polygonal cavities because the background objects beneath PV panels sometimes led to mis-classification errors. In order to reduce unnecessary area loss, we aggregated neighbouring polygons which were within 270?m distance to each other and eliminated holes in the PV vectors using the Arcgis 10.7 software. Hollow polygons with holes less than 8100 m2 (90?m?×?90?m) were set to be filled. Due to the complexity of land cover types in China, some PV plant classification errors still exist. To ensure the accuracy of our data products, we used Google Earth Pro to visually check each post-processed PV polygon and manually adjusted the contours when necessary. Afterwards, the PV polygons were overlaid with the administrative map of China to determine in which province each PV locates. The PV polygons were also overlaid with the global urban boundary data to determine whether each PV was installed in urban areas (inside the urban boundary) or rural areas (outside the urban boundary).

Data Records

Following the above methods, we created a vectorized dataset containing PV installations across China in the year 2015 and 2020 and named it “ChinaPV” hereafter27. The dataset can be downloaded at https://zenodo.org/records/14292571. ChinaPV contains the specific location as well as the size of each PV installation. This study generated two vectorized solar PV installation maps in China for the year 2015 and 2020. It includes the location and size of each PV installation. ChinaPV is delivered in “ESRI Shapefile” formats in the WGS-84 coordinate system. The attributes table of the PV polygons include the PV polygon ID, latitude and longitude coordinates of the centre point in each PV installation, the area (km2) and perimeter (km) of each PV, the name of province this PV locates, as well as whether this PV locates in urban areas or rural areas. The area and perimeter for each PV was calculated in the Asia North Albers Equal Area Conic projection in Arcgis. Besides, we are making efforts to produce China’s PV power station map at an annual basis. These maps will be released once generated in the future.

Technical Validation

PV classification results

Through visual interpretation of the misclassified cases, it was found that major PV detection errors distributed in areas with exposed rocks, mountain shadows, and polyethylene materials of urban buildings which exhibited reflection characteristics similar to PV panels. In addition, there were some salt-and-pepper noise and some small patches that could not be differentiated accurately. The presence of these patches may be attributed to environmental factors, where their spectral characteristics were similar to those of PV features, making it difficult to distinguish them accurately. After post-processing operations, the final results were significantly improved, as demonstrated in Fig. 4. Not only some hollow areas were filled (see Fig. 4b1–b4), but also the contour of each PV polygon was adjusted to better delineate the distribution of PV (see Fig. 4a1–a4).

Accuracy assessment on the PV classification results

After classification, we assessed the accuracy of PV classification results based on the 30% validation samples obtained in section “Training and test samples for PV detection”. Statistical measures including the overall accuracy, producer accuracy, user accuracy and kappa coefficient were calculated based on the confusion matrix of PV and NPV in the validation dataset. According to Table 1, the results revealed that the classification achieved an overall accuracy over 96% for both 2015 (OA?=?96.71%) and 2020 (OA?=?99.06%). The relatively lower accuracy in 2015 than 2020 is probably because the Random Forest classifier was trained using samples collected in 2020, while directly applied to the composite image in 2015.Table 1 The accuracy of final PV classification results.

Consistency evaluation and accuracy comparison with existing PV dataset

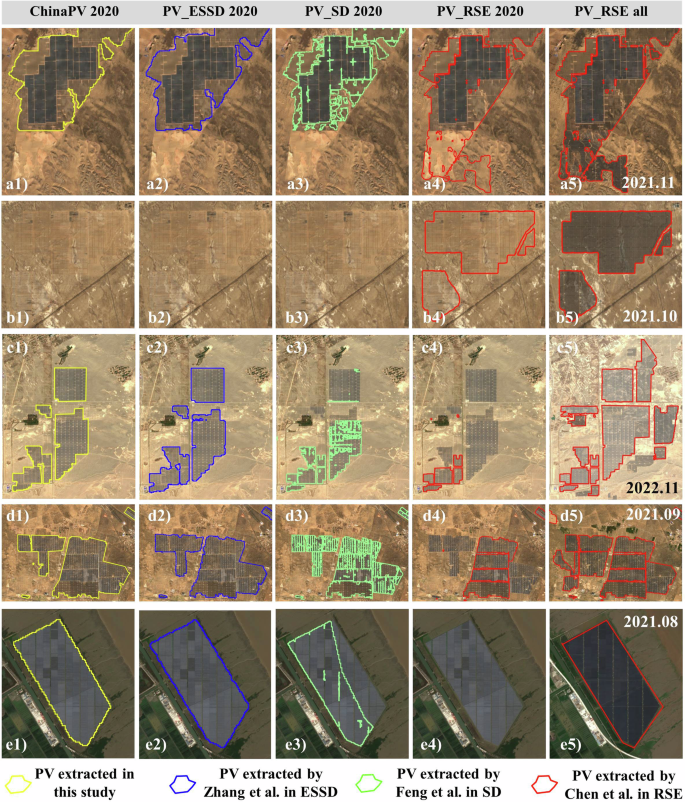

To verify the quality of our dataset, we compared ChinaPV27 in the year 2020 with three existing PV datasets in 2020. For simplicity, they were referenced as PV_ESSD28, PV_RSE29, as well as PV_SD30. The PV_ESSD is also a vectorized PV installation dataset in China, for the year 202012. It was produced by Zhang et al. using machine learning and visual interpretation methods with Landsat satellite data. The PV_RSE is also in vectorized format. It was extracted by Chen et al. using deep learning method from Sentinel-2 images of China in 2022. Each PV plant had an attribute of installation year, which was estimated from time series analysis using Landsat 5/7/8/9 images within each extracted PV area images. For comparison, we extracted polygons which were installed in 2020 and before 2020 in PV_RSE. The PV_SD is a 10?m resolution raster PV detection dataset in China, which was extracted from Sentienl-2 images for the year 2020 by Feng et al.30. For comparison, we converted the raster results to shapefile format using Arcgis.

First, the area of all detected PV installations in China for the year 2020 in four datasets were compared and presented in Fig. 5 and Table 2. According to Fig. 5, ChinaPV is generally in consistence with the previous datasets including PV_ESSD and PV_RSE. The total area of PV installed in 2020 is very close to each other among ChinaPV, PV_ESSD and PV_RSE. However, the total area of PV_SD is only 1936.58?km2, much lower than the other three datasets. This is very likely because PV_SD utilized a higher resolution at 10?m. The spatial resolution differences may lead to scale effect of the resulting PV area. Besides, unlike other dataset, PV_SD did not eliminate medium cavities inside each PV polygon (see Fig. 6c3). Another possible reason is that ChinaPV employed visual inspection and adjusted the contours when necessary, while PV_SD mainly removed salt-and-pepper noises and filled tiny holes in the post-processing. As a result, there were many undetected PV pixels in PV_SD (see Fig. 6c3, 6e3).

Table 2 Consistency of ChinaPV 2020 with existing PV database.

By overlaying ChinaPV with existing PV dataset and calculating the overlapping fraction, we conducted consistency evaluation and presented the results in Table 2. According to Table 2, ChinaPV has more similar performance with PV_ESSD than with PV_RSE and PV_SD. This is possibly because both ChinaPV and PV_ESSD are extracted from Landsat images. However, when referred to PV_RSE, the overlapping fraction is lower. This is probably due to two reasons: (1) PV_RSE can detect fine scale PV due to the use of Sentienl-2 images, which has a higher spatial resolution at 10?m compared to Landsat-8 at 30?m; (2) PV_RSE wrongly estimated the installation date of many PV polygons. For example according to Fig. 6a4, 6a5, PV_RSE overestimated installed PV in 2020. The southern parts of PV in Fig. 6a4 were actually built in the year 2021 instead of 2020. The same errors can also be observed in Fig. 6b4, 6b5. Sometimes, such time estimation errors lead to underestimation of PV in PV_RSE. For instance in Fig. 6c4, 6d4, 6e4, PV_RSE failed to detect PV already installed in 2020. It is worth noting that Chen et al. also pointed out that such time detection errors exist in PV_RSE, out of 138 test sites, their method wrongly estimated the installation time in 14 sites (about 10%).

Furthermore, we employed the accuracy evaluation approach adopted by previous studies29 to quantitatively compare the accuracy of the above four PV datasets. First, we asked a different graduate student to randomly and manually digitized PV polygons across China with the help of Google Earth Pro. This resulted in a total of 9417 PV polygons as test samples. These test samples included PV polygons situated across various landscapes. Their spatial distribution is shown in the Fig. 7 below. These test samples were also uploaded with ChinaPV dataset at https://zenodo.org/records/14292571.

Afterwards, these test samples were used to evaluate and compare the accuracy of the four PV products, including ChinaPV27 in this study, PV_RSE29, PV_ESSD28, and PV_SD30. Metrics including accuracy (ACC), Precision, Recall, F1 score and IoU were used. The formulas for these metrics are as follows:

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

where TP (true positive) is the number of PV pixels corrected identified as PV, TN (true negative) is the number of NPV pixels corrected identified as NPV, FP (false positive) is the number of NPV pixels wrongly identified as PV, FN (false negative) is the number of PV pixels wrongly identified as NPV. For these metrics, higher values indicate more accurate results and better performance. The results are presented in Table 3 as follows. As can be seen, ChinaPV performs the best in terms of Accuracy, F1 and IoU. The PV_SD dataset has the highest precision and lowest recall, implying that there are more un-detected PV installations in this dataset, further corroborating our previous analysis in Fig. 6.Table 3 Accuracy evaluation of the four PV datasets in the year 2020.

Usage Notes

Users can employ our ChinaPV dataset in (1) analysing the spatial and temporal patterns of PV installation across China and in different administrative provinces; (2) analysing the spatial and temporal patterns of PV installation over different land cover and land use types; (3) collecting PV samples to train a deep learning model; (4) estimating the generated electricity and carbon mitigation effect from solar PV; (5) evaluating the environmental impact of PV on hydrology and local climate. These analyses can be achieved via GIS software and programming packages, such as ArcGIS, QGIS, GDAL, and GeoPandas.

Code availability

The code for initial PV classification on GEE as well as the training and test samples are available at https://github.com/qingfengxitu/ChinaPV. The post-processing was conducted using ESRI Arcgis 10.7 as well as Google Earth Pro.

References

- Luderer, G. et al. Residual fossil CO2 emissions in 1.5–2?°C pathways. Nat Clim Change 8, 626–633, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0198-6 (2018).Article ADS CAS MATH Google Scholar

- Walsh, B. et al. Pathways for balancing CO2 emissions and sinks. Nature Communications 8, 14856, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14856 (2017).Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

- Wang, P., Zhang, S. N., Pu, Y. R., Cao, S. C. & Zhang, Y. H. Estimation of photovoltaic power generation potential in 2020 and 2030 using land resource changes: An empirical study from China. Energy 219, ARTN 119611 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.119611 (2021).

- Gunderson, I., Goyette, S., Gago-Silva, A., Quiquerez, L. & Lehmann, A. Climate and land-use change impacts on potential solar photovoltaic power generation in the Black Sea region. Environmental Science and Policy 46 (2015).

- Zhang, X., Zeraatpisheh, M., Rahman, M. M., Wang, S. & Xu, M. Texture is important in improving the accuracy of mapping photovoltaic power plants: A case study of ningxia autonomous region, china. Remote Sensing 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13193909 (2021).

- Parida, B., Iniyan, S. & Goic, R. A review of solar photovoltaic technologies. Renewable and sustainable energy reviews 15, 1625–1636 (2011).Article CAS MATH Google Scholar

- Zou, H., Du, H., Brown, M. A. & Mao, G. Large-scale PV power generation in China: A grid parity and techno-economic analysis. Energy 134, 256–268, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2017.05.192 (2017).Article MATH Google Scholar

- Jiang, W., Tian, B., Duan, Y., Chen, C. & Hu, Y. Rapid mapping and spatial analysis on the distribution of photovoltaic power stations with Sentinel-1&2 images in Chinese coastal provinces. Int J Appl Earth Obs 118, 103280, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2023.103280 (2023).Article Google Scholar

- IEA, P. Snapshot of Global PV Markets 2021. (2022).

- Kruitwagen, L. et al. A global inventory of photovoltaic solar energy generating units. Nature 598, 604–610 (2021).Article ADS CAS PubMed MATH Google Scholar

- Stowell, D. et al. A harmonised, high-coverage, open dataset of solar photovoltaic installations in the UK. Sci Data 7, ARTN 394 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-00739-0 (2020).

- Zhang, X., Xu, M., Wang, S., Huang, Y. & Xie, Z. Mapping photovoltaic power plants in China using Landsat, random forest, and Google Earth Engine. Earth Syst Sci Data 14, 3743–3755, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-14-3743-2022 (2022).Article ADS MATH Google Scholar

- Yu, J., Wang, Z., Majumdar, A. & Rajagopal, R. DeepSolar: A Machine Learning Framework to Efficiently Construct a Solar Deployment Database in the United States. Joule 2, 2605–2617, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2018.11.021 (2018).Article MATH Google Scholar

- Wang, Z., Arlt, M.-L., Zanocco, C., Majumdar, A. & Rajagopal, R. DeepSolar++: Understanding residential solar adoption trajectories with computer vision and technology diffusion models. Joule 6, 2611–2625 (2022).Article Google Scholar

- Xia, Z. et al. Mapping the rapid development of photovoltaic power stations in northwestern China using remote sensing. Energy Reports 8, 4117–4127, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2022.03.039 (2022).Article MATH Google Scholar

- Liao, M. et al. Mapping China’s photovoltaic power geographies: Spatial-temporal evolution, provincial competition and low-carbon transition. Renewable Energy 191 (2022).

- Zhang, X. & Xu, M. Assessing the Effects of Photovoltaic Powerplants on Surface Temperature Using Remote Sensing Techniques. Remote Sensing (2020).

- Liu, P. et al. Evaluating the Accuracy and Spatial Agreement of Five Global Land Cover Datasets in the Ecologically Vulnerable South China Karst. Remote. Sens. 14, 3090 (2022).Article ADS MATH Google Scholar

- Belgiu, M. & Dr?gu, L. Random forest in remote sensing: A review of applications and future directions. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 114, 24–31, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2016.01.011 (2016).Article ADS MATH Google Scholar

- Zha, Y., Gao, J. & Ni, S. Use of normalized difference built-up index in automatically mapping urban areas from TM imagery. Int J Remote Sens 24, 583–594, https://doi.org/10.1080/01431160304987 (2003).Article MATH Google Scholar

- Tucker, C. J. Red and photographic infrared linear combinations for monitoring vegetation. Remote Sens Environ 8, 127–150, https://doi.org/10.1016/0034-4257(79)90013-0 (1979).Article ADS MATH Google Scholar

- Xu, H. Modification of normalised difference water index (NDWI) to enhance open water features in remotely sensed imagery. Int J Remote Sens 27, 3025–3033, https://doi.org/10.1080/01431160600589179 (2006).Article MATH Google Scholar

- Wang, J., Liu, J. & Li, L. Detecting Photovoltaic Installations in Diverse Landscapes Using Open Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sensing 14, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14246296 (2022).

- Zhang, X. H., Zeraatpisheh, M., Rahman, M. M., Wang, S. J. & Xu, M. Texture Is Important in Improving the Accuracy of Mapping Photovoltaic Power Plants: A Case Study of Ningxia Autonomous Region, China. Remote Sensing 13 (2021).

- Elvidge, C. D. et al. Fifty years of nightly global low-light imaging satellite observations. Front. Remote Sens 79 (2022).

- Wang, J., Liu, J. & Li, L. Detecting Photovoltaic Installations in Diverse Landscapes Using Open Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sensing 14, 6296 (2022).Article ADS MATH Google Scholar

- Liu, J., Wang, J. & Li, L. ChinaPV: the spatial distribution of solar photovoltaic installation dataset across China in 2015 and 2020 (v1.1) [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14292571 (Zenodo, 2024).

- Zhang, X. H., Xu, M., Wang, S. J., Huang, Y. K. & Xie, Z. Y. Mapping photovoltaic power plants in China using Landsat, random forest, and Google Earth Engine. Earth System Science Data 14, 3743–3755 (2022).Article ADS MATH Google Scholar

- Chen, Y. H., Zhou, J. Y., Ge, Y. & Dong, J. W. Uncovering the rapid expansion of photovoltaic power plants in China from 2010 to 2022 using satellite data and deep learning. Remote Sens Environ 305, ARTN 114100 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2024.114100 (2024).

- Feng, Q. L. et al. A 10-m national-scale map of ground-mounted photovoltaic power stations in China of 2020. Sci Data 11, ARTN 198 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-02994-x (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (No: BK20200722), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No: U2003201), and the Jiangsu Province Innovation and Entrepreneurship Doctor Program (No: 184080H10840).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Jiangsu Centre for Collaborative Innovation in Geographical Information Resource Development and Application, Nanjing, 210023, ChinaJing Liu, Jinyue Wang & Longhui Li

- Key Laboratory of Virtual Geographic Environment (Nanjing Normal University), Ministry of Education, Nanjing, 210023, ChinaJing Liu, Jinyue Wang & Longhui Li

- State Key Laboratory Cultivation Base of Geographical Environment Evolution and Regional Response, Nanjing, 210023, ChinaJing Liu, Jinyue Wang & Longhui Li

Contributions

Jing Liu: conceptualization, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing; Jinyue Wang: data curation, formal analysis, writing – review & editing; Longhui Li: conceptualization, writing – review & editing, supervision.