By the end of December, developers expect to flip the switch on the final electrical transmission projects built under the state’s Competitive Renewable Energy Zone initiative — a years-long effort to connect windy, largely secluded West Texas to growing cities that demand more power.

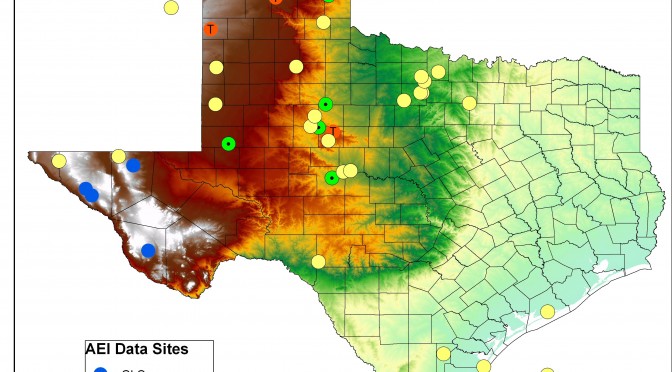

The finished product will stretch nearly 3,600 miles and will be able to send 18,500 megawatts of wind power across the state. That’s about 50 percent more capacity than is now installed in Texas — the country’s leader in wind energy production — and more than three times as much as any other state.

“It’s a major milestone,” said Terry Hadley, a spokesman for the Public Utility Commission. He said regulators will be on the lookout for any needed tweaks. Those changes could include adding equipment to decrease the energy lost over the longest-stretching lines.

Regulators and wind power advocates say the build-out, approved by the PUC in 2008, has spurred huge investments in wind energy by assuring developers that they’ll have markets for the energy their turbines churn out.

Texas isn’t the only state looking to add transmission for wind power, but other projects don’t match CREZ’s scope. Projects elsewhere — particularly those that stretch across state lines — have been slowed by a patchwork of sometimes conflicting federal and state regulations. Texas has avoided the biggest bureaucratic messes because most of its power lines stay within state borders.

And the presence of one grid operator — the Electric Reliability Council of Texas — in most of the state further simplifies the process.

That’s not to say planning for CREZ was a breeze. The routes, some of which proved controversial, were slowly mapped out in the PUC’s hearing room.

Landowners in the Hill Country were among those who tried to prevent the lines from crossing their property. They stopped one line and part of another after grid officials found it possible to upgrade infrastructure but serve the same purpose more cheaply.

The new transmission projects aren’t cheap. Texans will eventually shell out $6.8 billion to finance the entire build-out, according to a project update released this week by the PUC.

Electric ratepayers will bear the burden, but few have seen their bills creep up. The commission has approved CREZ fees from just three transmission service companies, with other filings winding through the system.

The new fees, Hadley said, will likely add several dollars to a residential customer’s monthly bill.

The estimated price tag has changed little over the past two years, but it is far higher than the $4.93 billion projection made in 2008. Inflation drove some of that increase, while the project’s changing shape was a bigger factor.

In calculating the original estimate, researchers assumed the power lines would follow the most direct routes. As the process played out, regulators minimized intrusion by redrawing routes to follow fences or roads. Those decisions added more than 600 miles of unplanned power lines.

Jeff Clark, executive director of the Austin-based Wind Coalition, sees the spending as well worth it. Texas’ wind portfolio is still growing, he said, and the cost of wholesale wind energy is falling as technology improves and grid operators find more ways to integrate wind with natural gas.

Across the state, grid operators are reviewing some 21,000 megawatts’ worth of new wind projects. Typically, about 20 percent of proposals are built, said Robbie Searcy, a spokeswoman for ERCOT. New projects in the Panhandle — including a planned 1,100-megawatt wind farm near Lubbock that promises to be the country’s largest — are expected to exceed the capacity of the region’s new transmission, meaning regulators may need to add even more lines.

“When we look back on the investment in CREZ,” Clark said, “it will be one of the most visionary investments the state has ever made.”