This story was produced in collaboration with Grist, a nonprofit media organization covering climate, justice, and sustainability for a national audience. Cover illustration by Amelia Bates/Grist.

It was a scorching August day at the Hoover Dam as three Trump administration officials gathered for a little celebration honoring pollution-free hydroelectricity. Inside the dam’s Spillway House Visitor Center, air conditioning thankfully kept people comfortable as the president’s appointees heaped praise on hydropower. A U.S. Department of Interior news release about the event calls hydroelectric dams such as Hoover —where the Colorado River slips between Arizona and Nevada — a “unique resource critical to America’s future, which supports the integration of other renewables like wind and solar onto the grid.”

But what went unsaid at the grip-and-grin was that one of those high-ranking officials, Dan Simmons of the U.S. Department of Energy doesn’t appear to fully support renewables. In fact, he has presided over his agency’s systematic squelching of dozens of government studies detailing its promise.

One pivotal research project, for example, quantifies hydropower’s unique potential to enhance solar and wind energy, storing up power in the form of water held back behind dams for moments when the wind isn’t blowing and the sun isn’t shining. By the time of the Hoover Dam ceremony, Simmons’ office at the Energy Department had been sitting on that particular study for more than a year.

In all, the DOE has blocked reports for more than 40 clean energy studies. The department has replaced them with mere presentations, buried them in scientific journals that are not accessible to the public, or left them paralyzed within the agency, according to emails and documents obtained by InvestigateWest, as well as interviews with more than a dozen current and former employees at the Energy Department and its national labs.

Bottling up and slow-walking studies is already harming efforts to fight climate change, according to clean-energy experts and others, because Energy Department reports drive investment decisions. Entrepreneurs worry that the agency’s practices under the current White House will ultimately hurt growth prospects for U.S.-developed technology.

“There are dozens of reports languishing right now that can’t be published,” said Stephen Capanna, a former director of strategic analysis for the Energy Department’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy —the office that Simmons runs — who quit in frustration in April 2019. “This is a systemic issue.”

Political interference is a pervasive practice targeting research funded by the DOE’s efficiency and renewables office, say federal researchers, who add that the pattern is intensifying. The broad scope of meddling revealed by InvestigateWest’s two-month investigation is also affirmed by a letter sent last week to Secretary of Energy Dan Brouillette from the U.S. House Science Committee. The letter cites an August 2020 InvestigateWest story that detailed the political takedown of a study dating back to 2016. Ir also lists six more DOE-funded studies that were “unduly delayed or modified by senior DOE officials” and another four completed reports that “are yet to be released.”

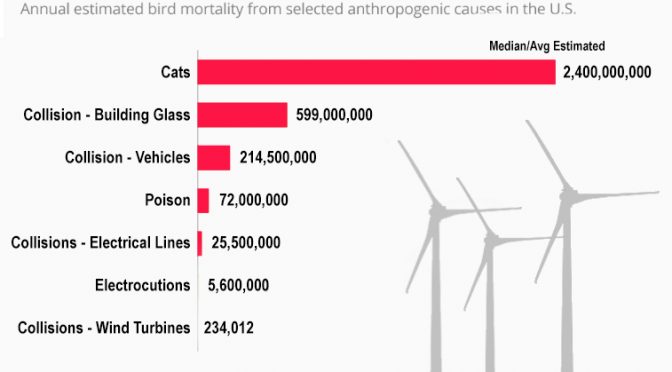

Trump appointees blocked a report estimating that Energy Department-funded research and development on wind energy has created $31.4 billion in economic and societal benefits. Pictured: A wind turbine in Pennsylvania. (Peter Fairley/InvestigateWest)

Meanwhile, insiders contacted by InvestigateWest point to two recent developments escalating the political impact on science in the Energy Department.

First, in January, Simmons’ office began cutting the frequency of annual or quarterly market updates to every other year. The delay could hurt U.S. competitiveness on clean energy innovation, according to renewable energy entrepreneurs.

“Many investors, inventors and companies use those reports to guide their decision-making about how, where and when to deploy capital, so the politicization and adulteration of this critical scientific process introduces the risk of slowing down investments or causing companies to make bad bets,” said Michael Webber, chief science and technology officer for Paris-based multinational energy firm ENGIE, and a professor at the University of Texas at Austin. “That will take a toll.”

And then in the spring, word trickled down that scientists would need political appointees’ signoff to publish their work in peer-reviewed science journals, according to inside sources. Energy researchers say such a demand was previously unthinkable, because government scientists have long been able to share their work with other scientists without political interference. Dan Kammen, a veteran energy expert at the University of California, Berkeley, calls this development “chilling.”

Good work = Bad news

The political shenanigans within the Department of Energy’s clean energy research operation stem from a fundamental misalignment between Simmons’ $2-billion-a-year-plus operation and its masters. Congress has tasked the efficiency and renewables office with advancing alternatives to fossil fuels. But President Donald Trump is a fossil fuel booster who belittles renewable energy, calling solar panels expensive and linking, without evidence, wind turbines to cancer. His annual budget proposals have consistently targeted the office for funding cuts of 65% to 71% — though bipartisan Congressional votes have spared its coffers each time.

That discrepancy put Trump’s original appointees — Simmons and Alex Fitzsimmons, Simmons’ chief of staff until he was promoted within the office last year — in a no-win situation. “They were never going to get a pat on the back for anything that we put out that was talking about how we could support renewables or efficiency or electric vehicles or anything like that,” Capanna said. “They were only going to hear about it if we pissed off somebody who cared about coal or nuclear or [blocking] carbon pricing.”

Trump’s Energy Department professes to follow an “all-of-the-above” energy strategy, which purportedly includes support for renewable energy. However, Secretary Brouillette and his deputy secretary, Mark Menezes, are both former lobbyists — Brouillette for Ford Motor Company and Menezes for power utilities. The industries they represented stood to lose money due to technological advances paid for by the efficiency and renewables office. For example, power plants combining solar panels and big batteries can — like hydroelectric dams — reduce demand for natural gas “peaker” plants favored by the electric power producers Menezes used to serve. And shifting to electric vehicles requires costly retooling by automakers.

When government scientists’ reports began appearing in the news — announcing innovations or market growth in the renewable space, or exploring policy options and grid upgrades that would further boost renewables — Trump administration political appointees were initially caught off guard. Then, they hit back.

A document obtained by InvestigateWest shows that Fitzsimmons in May 2018 established a system that enabled the appointees to intervene and, if necessary, consult their superiors before politically sensitive reports went out. It mandated that those addressing topics of greatest sensitivity — including studies that compared different energy sources or projected the future prospects of renewables — be designated “Tier 1” and flagged for review by Simmons and Fitzsimmons. (All other research was designated “Tier 2.”)

China is electrifying its economy by building high-voltage direct current power lines such as this one in the arid northwestern province of Gansu. Similar lines are contemplated by several studies buried by the Trump administration, including NREL’s Electrification Futures Study. (Peter Fairley/InvestigateWest)

Prepublication review of Tier 1 reports enabled the Energy Department’s top political appointees to scrutinize scientists’ findings and demand changes or prevent their release. Such interference has occurred regularly since, according to emails, documents and interviews obtained or conducted by InvestigateWest.

Federal research staffers told InvestigateWest that they did not immediately grasp the full import of the novel review requirements after Fitzsimmons issued the new reporting demands. They didn’t have much time to think. National Renewable Energy Laboratory researchers were given just six days in late May 2018 to declare any reports due out in the following three months, according to an email from the lab’s leadership. Researchers said it was August 2018, when that lab’s Interconnections Seam Study hit a wall, that the implications sank in.

Fitzsimmons, along with another official who temporarily subbed in for Simmons during his Senate confirmation, buried the report, known as the “Seams” study, because it projected the accelerated demise of the coal industry, as documented previously by InvestigateWest. “Now we’re getting real on this,” is how Charlton Clark, a former grid integration program manager at DOE’s Wind Energy Technologies Office, remembers the message amid the study’s fall 2018 takedown.

Last month, the chair of the U.S. House Science Committee, Democratic Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson of Texas, wrote to Brouillette and cited InvestigateWest’s reporting in demanding action and answers regarding the Energy Department’s “efforts to suppress” the Seams study. Two days later, on September 24, the House passed an energy bill that ordered its release. Last week, two years and two months after erasing Seams’ results from its website, the National Renewable Energy Lab posted a new version approved by the Energy Department. “The end result of these changes is that the findings are diluted,” one study author told InvestigateWest.

After Seams was ensnared, the number of studies caught up by the political crackdown snowballed. According to a May 2019 email obtained via FOIA, for example, a pile of wind energy studies were stuck. “We are getting a backlog of reports in Tier One situation,” wrote Valerie Reed, then acting director of the Wind Energy Technologies Office, to her boss’ chief of staff.

The pileup left scientists — and their work — dangling. “There’s no feedback,” one National Renewable Energy Laboratory researcher said. “It just goes into a black hole.”

Career employees call the lack of transparency a self-serving shield that protects the administration from accusations of censorship. They also call it a dereliction of duty. As one efficiency and renewables office staffer put it: “They’re not doing their jobs. Period. Because they don’t want to have to say no. They don’t want to get caught saying no.”

Unprecedented interference

All administrations exercise some level of control over Department of Energy research, according to veteran scientists interviewed by InvestigateWest. What distinguishes the Trump administration, they say, is the scale of the censorship and the secrecy surrounding it. “Unprecedented,” is what three senior national laboratory researchers who emailed InvestigateWest call the logjam at the efficiency and renewables office. They say they are personally aware of at least 25 reports just from the national labs that have been delayed for over six months during Trump’s term. For comparison, they claim they can count on one hand the studies held up that long during Barack Obama and George W. Bush’s combined 16 years in the Oval Office.

Interviews and emails reveal that the affected studies originate throughout the efficiency and renewables office’s programs. Many of the blocked studies favor renewables over the fortunes of traditional energy sources. One is a congressionally mandated study of a national “zero-emissions energy credit” scheme that incentivizes renewable energy, capture of carbon dioxide from coal and gas-fired generators, and nuclear power. Capanna argues that the study was delayed because it projected that incentives for zero-carbon power would protect existing nuclear plants from shuttering, but might not prompt construction of new reactors favored by the Trump administration. A group of stalled solar power studies, meanwhile, affirm prior research showing multiple mechanisms to cost-effectively scale up solar in the western U.S., undermining Trump administration efforts to protect aging power plants.

In addition to studies held in limbo, others sent for review at the efficiency and renewables office have been downgraded to conference presentations or canceled outright. The National Renewable Energy Lab, or NREL, based in Golden, Colorado, reviews all reports that it sends to Washington and, according to insiders, holds some back entirely. “We have a whole review process that involves upper management where anything controversial gets reviewed and discussed and most likely taken out,” said a lab researcher contacted by InvestigateWest.

Some studies slated for publication as official Energy Department or national lab reports, meanwhile, have been submitted instead to scientific journals. Articles in journals are usually less detailed and are published outside the public domain, thus reducing a study’s impact. But it is preferable to not publishing at all.

Researchers and some high-ranking career staff have tried in vain to push back against what they see as violations of the Energy Department’s scientific integrity policy. That rule, created in 2014 and updated a few weeks before Trump’s inauguration, is intended to protect the freedom of Energy Department researchers to openly discuss and publish their research, and expressly prohibits direct actions or coercion to “suppress or alter scientific or technological findings.”

But neither of the Energy Department’s deputy secretaries, Brouillette or Menezes, appointed a scientific integrity officer, as the policy requires, to police its provisions and resolve disputes. And federal researchers say complaints to lab directors and Energy Department officials have been ineffectual. Multiple sources within the agency report that David Solan, a political appointee who arrived at the efficiency and renewables office last year, has pushed back against allegations from staff that blocking publication violates Energy Department guidelines. He has told career employees that the policy does not protect those researchers producing the kind of “techno-economic analysis” frequently designated as Tier 1. (In fact, the policy explicitly covers all Energy Department employees and contractors.)

Johnson, the chair of the House Science Committee, zeroed in on scientific integrity in her Sept. 22 letter to the Energy Department. She told Brouillette that InvestigateWest’s reporting “suggests a number of violations of your own Scientific Integrity Policy.” She has demanded a briefing on what happened to the Seams study, as well as the Energy Department’s failure to appoint a scientific integrity officer — something Brouillette promised to do last year.

Johnson’s committee has also been searching for whistleblowers. DOE researchers say they have, until now, shied away from taking complaints to the department’s inspector general, Congress or the media. They fear retribution that will harm their careers and perhaps even prompt them to leave their federal positions — which Aaron Bloom, the manager of the Seams study, did in late 2018. And they say lab leaders fear collective retribution against their institutions. As the NREL researcher said of the reasoning of his lab’s director: “I get his position to some degree. Pissing off people within DOE or the administration more broadly could make it more difficult to get the large investments in infrastructure that the lab has been good at getting in recent years.”

NREL spokesperson David Glickson told InvestigateWest that the lab’s internal review process did not delay or cancel any reports. He also denied that agency director Martin Keller had said that challenging the Energy Department’s reviews might jeopardize the lab’s infrastructure projects. InvestigateWest also reached out to Energy Department officials for this article, including Brouillette, Menezes, Simmons, Solan and Fitzsimmons. Neither they nor the agency responded to our repeated requests.

Reports on integrating more solar power on U.S. grids have been collecting dust on the desk of Energy Department Deputy Assistant Secretary David Solan since his appointment 17 months ago. Pictured: Solar panels at Anahola on Kauai, Hawaii. (Peter Fairley/InvestigateWest)

Unnatural consequences

What worries scientists inside and outside of the Energy Department is a broad stifling of intelligence and expertise within its ranks— resulting in potentially serious environmental and economic consequences. Researchers say attacks on their work — and the anemic protection their managers can muster – is undermining morale, and degrading federal clean-energy research. Entrepreneurs worry about the U.S. falling behind.

Many researchers, such as Bloom and Stephen Capanna, have already left. There could be a further flood of departures if Trump wins reelection. Dan Kammen, the UC Berkeley scientist, says that even if there is a change of administrations in 2021, Trump’s first term may have driven out enough “outstanding and committed” civil servants to have a lasting impact on federal research.

“Censorship drives these individuals out,” Kammen said. “It is a death blow to the employees the agencies most need.”

The impact of that brain drain could radiate beyond the agency. Less expertise in-house diminishes the Energy Department’s ability to make informed decisions about the science that it funds at the national labs, in academia and in industry. “We’re literally here spending billions of dollars on behalf of the American taxpayer; we need that knowledge to do so as well as possible,” says one career employee in the efficiency and renewables office.

Other experts see more pernicious effects. Solar entrepreneur and investor Jigar Shah says the cancellation of quarterly and annual solar benchmarks will directly disadvantage solar energy’s market appeal.

State public service commissions and other agencies use the Energy Department’s benchmarks to assess investment plans put forward by utilities, Shah noted, and less frequent reporting will delay the incorporation of solar’s rapidly falling costs into those evaluations. “Our costs have come down so dramatically that if the numbers are not updated regularly, then government regulators and others are kept in the dark,” he said.

An Energy Department insider says the new reporting schedule came down from Menezes in January, and was justified as a cost-saving measure. That rationale is debatable since data collection, which represents the greatest cost, has not slowed down. Shah sees it as part and parcel of a preference by both Trump and his administration for fossil fuels over solar and wind energy.

True to its pattern, the Trump administration proposes cutting the funding of the efficiency and renewables office by 75% in its latest proposed budget, once again undercutting its claimed all-of-the-above approach for future energy sources. In contrast, the administration’s Fiscal Year 2021 budget requests only a 3% trim for DOE’s fossil fuel energy office.

If clean energy research remains stalled at the Energy Department — or, worse still, a second Trump administration succeeds in defunding it — it’ll be bad news for hopes of accelerating a transition to cleaner energy and slowing climate change.

The die may have already been cast at Lake Mead. Behind Hoover Dam’s 72-story wall of concrete, the nation’s largest reservoir has been hit hard by two decades of drought — so hard that plummeting water levels are suppressing the dam’s energy output.

According to recent research, the 21st-century megadrought in southwestern North America marks the region’s driest spell in 500 years. The scientists who made that assessment blame 47% of the drought’s severity on warmer temperatures and lower precipitation driven by climate change. In other words, greenhouse gases, primarily from the combustion of fossil fuels, turned an “otherwise moderate drought” into a catastrophe.

And the latest projection by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the federal agency that operates the dam, shows five more years of drought ahead.

With a Trump victory in November, federal researchers may expect nearly five more years of a publishing drought, as well.

TRUMP ADMINISTRATION’S CLEAN ENERGY RESEARCH LOCKBOX

Documents obtained by InvestigateWest identify at least 46 reports from almost every program within the U.S. Energy Department’s energy efficiency and renewables office and seven national labs that have been stalled, downgraded, or spiked. They include:

- A study of hydropower’s future value and up to five more studies commissioned by DOE’s hydropower office from four national labs, including Pacific Northwest, Idaho, and Argonne National Labs.

- At least two dozen reports from the Energy Department’s solar program, of which at least 10 have been trapped in review since 2019. Among those stuck in review is a pair of National Renewable Energy Lab studies on grid integration of solar power in the western U.S., which is sitting with Energy Department Deputy Assistant Secretary David Solan since his appointment 17 months ago.

- As many as 16 reports managed by the efficiency and renewables office’s strategic priorities and impact analysis team. They include a congressionally mandated study, requested in 2017, exploring the impact of a national “zero-emissions energy credit” scheme incentivizing renewable energy, nuclear power, and CO2 capture by coal and gas-fired generators.

- At least a dozen reports from an Energy Department grid modernization initiative, including an exploration of renewable energy options for large utility customers written by experts at the utility Xcel Energy, Walmart, and the World Resources Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank.

- Potentially more than 10 reports from the DOE’s wind, transportation, advanced manufacturing, and biofuels offices. One report, which was shunted to a science journal, estimated that Energy Department R&D on wind energy has created $31.4 billion in economic and societal benefits, delivering an 18-to-1 return on public investment; the journal it ran in charges nearly $8,000 for an annual print subscription.

This story was supported in part by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.