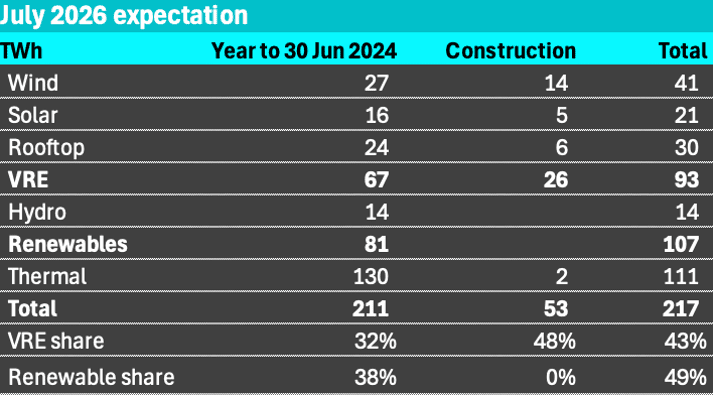

Renewable generation should be around 50 per cent of supply on Australia’s main grid by July, 2026, although it might be a bit less depending on progress on the second stage of Golden Plains, which will be the country’s biggest wind farm – at least for a time – when complete.

To get to 80 per cent by 2030 will partly depend on what happens to demand. If demand is flat, then capacity capable of supplying around 67 terawatt hours (TWh) a year will be needed. After allowing for rooftop solar, I reckon that equates to about 25 gigawatts of new capacity, maybe a bit more.

That’s a heck of an ask, but in my opinion still possible and broadly in line with the objectives and scale of the Capacity Investment Scheme (CIS). I’ll have more to say on the role of the CIS once I get round to talking about ITK’s price forecasts, but that can wait. We’re talking capacity and output in this not.

I hadn’t updated the variable renewable energy (VRE) capacity details for about 3 months. Using a summary from www.renewmap.com.au possibly the most interesting new web site for us energy nerds to be developed in the past year, I’ve updated the under construction and operating tables for wind, solar and batteries in the NEM.

I rely on the RenewMap team’s definitions of operating and under construction. As an example last time I did the update, back in March, Rye Park was shown as under construction even though 50% of the capacity was producing.

For this exercise the exact definitions don’t matter. I’m interested in understanding how much VRE (variable renewable energy) the NEM is capable of producing, and a different question of how much it’s likely to actually produce.

Actual production depends not just on the weather, and this early Winter has been a strong reminder of not just wind drought but also how important Queensland is going to be to the Southern States as the VRE roll out continues, but also on MLFs (marginal loss factors) and economic curtailment.

Economic curtailment can itself occur for two reasons.

Reason 1 is that prices go negative and despite the value of RECs various PPA agreements require a producer to shut down when prices are negative. Reason 2, not so common yet but will become more so is that the total of wind and solar production exceeds demand.

As long as there is “must run” thermal generation in the system we will get more curtailment than is needed in a highly renewable system. At the moment there are 1000s of MW of coal and gas that have to run 24/7. That generation is loss-making typically in the middle of the day and results in excess production and some curtailment.

For instance in QLD even in Winter, even without the 1.6 GW of wind nearing operation, prices are still going negative at lunch time.

QLD can export most of its surplus to NSW but clearly if prices are negative it’s not getting rid of all of it. The other option for a surplus of lunchtime power is to charge it up for storage because the spreads are still excellent over $300/MWh in all States except Victoria.

That’s a lot of margin for battery developers if you consider the rapidly falling cost of batteries. Ny understanding is that a 2 hour battery that cost say A$650/KWh a year ago now starts with a $4 and still falling. The reduction is due to a long expected reduction in cell costs.

So, because the reduction is in the cell costs there is basically a strong incentive to increase duration. In turn with more duration less of the battery’s revenue will come from frequency control and more from trading the daily market.

Over the next three years this will play out as a flattening of evening price peak, reducing gas opportunity, at least outside of wind droughts, and maybe taking some stress off middle of the day prices.

No matter how many utility batteries are built unless there are lots of household and network batteries it’s likely that rooftop solar will still make life very tough for utility generators at lunch time.

That’s because a rooftop solar system has a capacity factor of at least 14% which works out to say 3.5 MWh per day on average.

So if we are installing over 2 GW of rooftop solar a year, you need 2 GW of 4 hour batteries just to deal with the incremental supply. Never mind all the utility solar as well. Much better to have 1 GW of 8 hour residential and community batteries installed each year.

And if the reason utility battery costs are falling strongly is because of falling cell costs, then it’s likely that household battery costs can also fall quite a lot. I’ve only been waiting a decade for that to happen.

Anyhow, all that is a bit off today’s topic which is existing and new supply. I’m only going to show the broad totals.

Where we are and the road out to the next bend

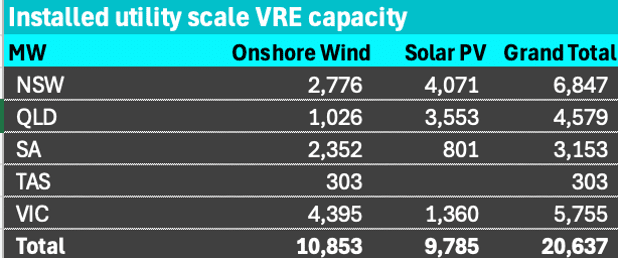

First existing installed utility VRE capacity has increased from 19.9 GW in March to 20.7 GW. Of course there is a similar quantity of rooftop solar.

Wind and solar capacity. Source: RenewMap

Wind is up by about 300 MW and utility solar by about 500 MW. However output is well down due to the wind drought. No surprise there. Where the surprise will be is when the wind picks up again.

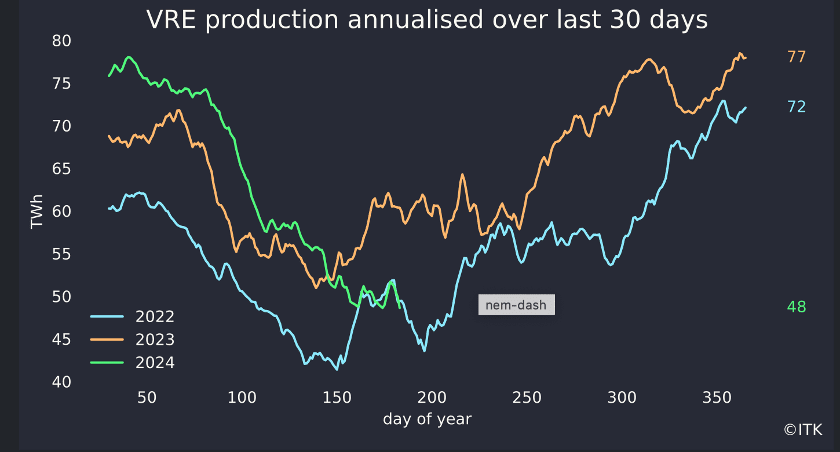

VRE production. Source: NEM Review

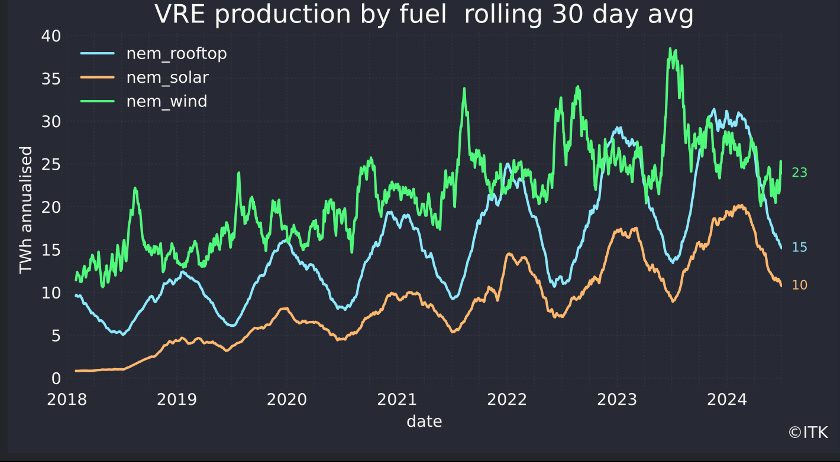

VRE by fuel. Source: NEM Review

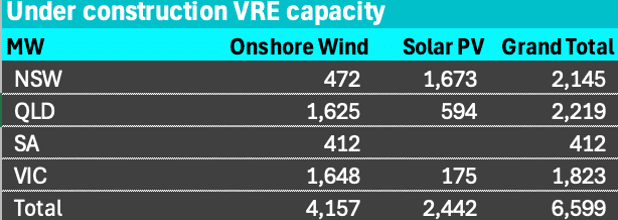

Turning to under construction

The total remains about 6.9 GW, boosted by Golden Plains stage 2 in Victoria.

Under construction VRE. Source: RenewMap

Pleasingly wind capacity is going to increase 40% and even more pleasingly more than 1/3 of that is in QLD.

Heading close to 50% renewables in two years

Wind actual output over the past year is 27 TWh, on 10.8 GW of capacity, and that works to an average capacity factor of 28%. Even allowing for older technology, a figure over 30% should be expected.

I guess the difference is the recent wind drought, and that there is always some capacity undergoing maintenance, and MLFs. Generally I do do my forward forecasts on a rosier basis.

Even allowing for this year’s worst I’ve seen in a decade and presumably unusual wind drought the 365 day total for VRE is around 31% of total energy supplied in the NEM. That’s after curtailment and MLF stuff.

And, since we are counting, NSW solar share is also down on the previous corresponding period even though capacity is up.

Putting it together and assuming all new capacity is operating within two years, I get a 49% renewable share by this time in 2026. Essentially that’s close to a bankable share, leaving aside only construction and connection risks.

July ‘26 VRE and share. Source:ITK

Batteries

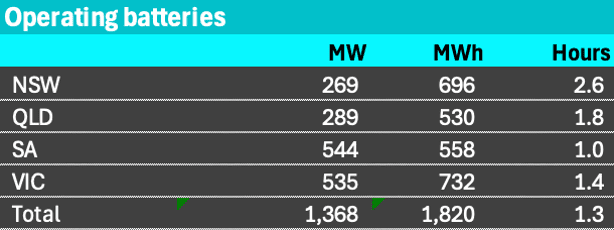

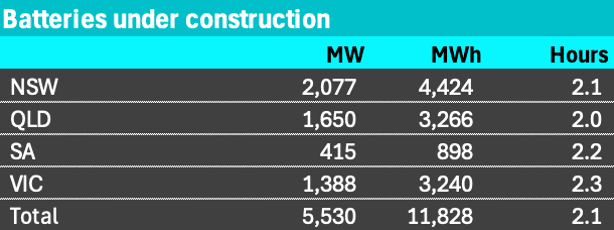

Battery gigawatts are increasing 400% from an operating 1.4 GW to 6.7 GW total, counting the 5.5 GW under construction. The delayed Capital battery in the ACT is now counted as operating, although some may wonder as it is operating at very low levels.

As impressive as that is, the GWh capacity is going from 1.8 to 13.6 GWh, a 650% increase. Batteries under construction have an average of 2.1 hours of duration, up from the 1.3 hours of the existing fleet. I’ve already talked about my expectations that this will increase a lot further.

Operating batteries. Source: RenewMap

Under construction batteries. Source: RenewMap

People can talk about pumped hydro till the cows come home. If Battery costs have fallen 23% in 18 months and are still falling as global capacity ramps up, I would need a crystal clear business case to compete with them. Don’t forget the generally much better round trip efficiency of batteries.

Batteries are moving from a sideshow to centre stage

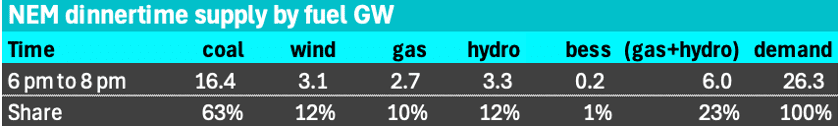

Right now batteries pretty much shadow price gas, in some cases demanding a premium. That’s possibly because the existing battery fleet gets more than half its revenue from ancillary services etc.

Even though some of the new batteries will be used for transmission reliability and other system services there is clearly going to be way more capacity available for day trading. I am reminded of the old stockbroking joke — Q: “How do become a small day-trader?” A: “Start as a big day trader.” Nevertheless.

The figure below shows that gas and hydro supply a median 6 GW (23%) of dinner time demand. Even if only 3 GW of the batteries under construction start trading in that dinnertime space they will probably end up dropping those peak prices significantly, at least that is my expectation.

Equally they will represent an even bigger share of midday demand and so have the potential to lift midday prices quite a bit as well.

Peak demand fuel supply. Source: NEM Review, ITK

David Leitch is a regular contributor to Renew Economy and co-host of the weekly Energy Insiders Podcast. He is principal at ITK, specialising in analysis of electricity, gas and decarbonisation drawn from 33 years experience in stockbroking research & analysis for UBS, JPMorgan and predecessor firms.

David Leitch, reneweconomy.com.au